by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by David J. Lobina

Having written for 3 Quarks Daily since July 2021, with the first entry coming out around the time of my birthday (two anniversaries to celebrate in July since then for me!), it has recently dawned on me that I have tended to write long “series” of articles here at 3QD Tower – but also, that I have made quite a mess of it at times.

Depending on how you gather up the posts, two series out of seven have not been completed at all, despite assurances given and promises made, and not every series has been posted in chronological order, which doesn’t make for a very uniform reading experience (but who reads this stuff anyway?!).

Given that this is the last entry of the year, I thought it would be a good idea to bring some order to my Monday Column, tie up some loose ends, and in addition anticipate some of the topics and arguments I want to run in 2024 – a New Year’s resolution of sorts, though as I will mention below, I had already announced in the past that I would tackle some of the very issues I shall list in this post. In my defence, some of these topics can be quite controversial, so perhaps I can be forgiven for the broken promise. Read more »

by Rafiq Kathwari

As Fareed drove in soft rain through red lights to Maimonides, my sister-in-law Farrah, and I sat in the back seat of the sky-blue Volkswagen van.

“Kicking,” she said, placing my hand on her round belly. Shy, I gazed at her polished toes in flip-flops.

A stork dropped a boy in Brooklyn eight years to the day JFK was slain in Dallas. New alien in New York, I babysat my curly-haired nephew in a stark rental on Park Avenue where the doorman first thought of us as the move-in guys, and where our Numdha rugs, hand-made in Kashmir, screamed to come out of our walk-in closets.

“Make money fast carpeting America from sea to shining sea,” grandfather had penned in an aerogram. Fareed rode the subway to Pine Street; Farrah was a cashier at Korvettes. The boy and I together discovered Big Bird on a Zenith console, my first TV exposure at age 22.

I watched the boy dunk hoops in purturbia, his long hair swishing to Metallica’s “Disposable Heroes.” He enrolled in the local chapter of the National Rifle Association, his dad’s rifle slung across the boy’s shoulder to hunt jackrabbits upstate.

He climbed a peak one summer in Kashmir, a paradise in pathos, a heated topic at our dinner table, but on the periphery of America’s mind, rarely mentioned on the Evening News, never on “All in the Family,” a popular sitcom that dared to shake America’s somnolence even as B-52 bombers rained napalm on Vietnam, fueling our rage.

In our hearts we knew we had to do what we could with what we had to help untie the Gordian knot of the Kashmir dispute, never again to let mad men tear apart husbands from wives, siblings from siblings, sons and daughters from mothers and fathers across the Line of Control since 1947 when India divided herself.

I can imagine how our family history seized my nephew’s receptive mind as he and his mates chilled every Sunday at the Islamic Cultural Center on California Road in Eastchester, once a Greek Orthodox Church, now embraced as a house of worship by a fresh wave of immigrants anxiously learning new ways of seeing and thinking.

Eager to impart their native cultural heritage to American-born kids, parents seemed unconcerned as weekday shop owners moonlighted as Sunday school teachers who were seemingly unable to equate the paradox of America’s ample prosperity at home with its wanton militarism abroad. Read more »

by Carol A Westbrook

It all began about 4.5 billion years ago, give or take a few millennia. The earth was still young, having been formed by the accretion of material that orbited around the sun. It was a young, moderate-sized planet, and, like the other planets in the solar system, it spun like a top as it rotated around the sun, with an axis that was parallel to the sun’s rotational axis. This configuration was the most stable for the planets in the solar system, though today only Mercury and Jupiter still have an axis that is parallel to the sun’s.

On that day, 4.5 billion years ago, an erratic planet about the size of Mars, called Theia, came crashing through the solar system and collided with the young Earth. This was not the same collision that killed most of the dinosaurs, which happened about 66 million years ago. The collision of the two planets resulted in the formation of the moon. But there was another significant result of this collision – the Earth’s axis shifted, from a position parallel to the sun’s, to one that is off by 23°! This tilt is the reason we have seasons.

The change in the earth’s axis away from parallel to the sun means that during the year, with Earth’s rotation around the Sun, the northern hemisphere will be pointing toward the Sun for about half the year, warming the earth and giving us summer. In the other half of the year it will be pointing away from the Sun, giving us cooler temperatures, or winter. The transitional seasons, spring and fall, are accompanied by more neutral temperatures. Read more »

by Martin Butler

Given the increasing ubiquity of technology in all our lives, it’s surely time to consider what may sound like an obvious, even stupid question but one that is actually vitally important: What is technology for?

At its simplest, technology can be understood as a tool which enables us to reach a particular end; a chimp using a stick to extract honey from a tree trunk, for example, a means to an end. That approach is crucial to our perception of the place of technology in the modern world. I visit a shop (means) to buy something (end). I get on a train (means) to arrive at a destination(end). To be able to engage in means-ends activity of any complexity is surely a sign of intelligence, showing purpose and imagination in that it seems necessary to imagine a state-of-affairs in the future that has not as yet come to pass, and of conceiving a way to achieving it. The end would be unattainable without the technology, just as the internet enables working from home in a way that would be impossible without it. On this model much technological innovation is about devising more efficient means of achieving particular ends, even though the ends were still achievable prior to the innovation. By ‘more efficient’ we mean meeting ends more quickly, doing it in a way that requires less human effort and often on an increased scale. The key innovations that were pivotal in the Industrial revolution were, for example, the machines that allowed spinning and weaving to take place on an unprecedented scale.

The main features of this model are that the means and the end are distinct, and the end is something we have identified as desirable. On these assumptions technology will always seem positive simply because it allows us to access something desirable that was previously unattainable, or, to access something desirable more efficiently than was previously the case. This model is taken as common sense in the modern world and it at least partly explains why technology is given pride of place within our culture.

But this is a misrepresentation of the place of technology in human life, principally because the relation between means and ends is not as simple as the above model suggests. Read more »

by Barbara Fischkin

In 1919, after a brutal anti-Semitic pogrom in a small Eastern European shtetl, my grandfather knew that his wife and three young children would be better off as refugees. He prepared them to trek by foot and in horse-drawn carts from Ukraine to the English Channel and eventually to a Scottish port. Finally they sailed in steerage class to the United States. My grandfather was a simple watchmaker—and one of the visionaries of his time. Europe, he told his tearful wife, was not finished with murdering Jews, adding that things were likely to get much worse. And so, my grandmother became a hero, too. She said farewell to her mother and sister, knowing she would never see them again. In Scotland, she descended to the lower level of a ship with her children—my mother, the eldest, was seven years old. My grandmother traveled alone with her children. My grandfather was refused entry to the ship. He had lice in his hair. He arrived in the United States weeks, or possibly months, later.

My grandfather, Ayzie Zygal of Felshtin, Ukraine became Isaac Siegel of Brooklyn, New York, where he lived for the rest of his life. In his later years he spent summers in the Catskill Mountains, always asking to be let out of the family car a mile before reaching Hilltop House, a bungalow colony. My grandfather wanted to walk that last mile along the local creek. It reminded him of the River Felshtin. He never regretted coming to America.

My grandparents died, in Brooklyn in their early sixties. My grandfather had been poisoned by the radium he used on the paint brushes in his shop to make the hours glow. He licked them, with panache, to make them sharper. My grandmother had a heart condition, exacerbated by diabetes. They were both gone before I turned three.

They had lived much longer than they had expected they would in 1919.

I was told my grandfather left Europe to save his family’s life. And because my mother narrowly escaped death. I was told he did not believe there would be any more miracles. Read more »

Regarding quantum chance, why

(or more simply) does the world exist,

and if it does, is it funny?

There might just as well be nothing

instead of the risible sun which makes me laugh

when it comes up coincidentally

with the punch line of a joke

that also could never have existed

had some unknown condition

not brought a comedian to the point

of standing up during the cascading series

of events of a million million millennia

and, imagining the humorous potential of bars,

created stories of characters who might

walk into one:

tales of lives, fictional yes,

but which in consciousness ring clear and true

because they touch and plumb the essence of our

inexplicably absurd existence evoking laughter

as we continue our desperate mining of the void

which in a universe without mind would have been

forever cloaked, forever unknown to anyone,

leading to some nada impossibly mysterious

or moot

………….. —no joke

Jim Culleny

by Rebecca Baumgartner

I’m currently reading The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in translation, and it’s got me thinking about how much we rely on translators to bring us literature from around the world, and how important it is to be able to trust what they tell us. I can only imagine the patience and creativity, the erudition and intuition, required to be a good translator. I’m deeply beholden to every translator who has enriched my life by unlocking the magic of Anna Karenina, Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet, War and Peace, A Young Doctor’s Notebook, the novels of Carlos Ruiz Zafón, the novels of Anna Gavalda, The Three Musketeers, Beowulf, the haiku of Issa and Basho, all the stories of Greek mythology, and now – The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

The duty of a translator assumes outsize importance once you get invested in a story. It’s crucial they get it right; you have to be able to trust their interpretation and sense of style. You want them to be faithful to the spirit and letter of the original, but if you had to prioritize one over the other, you want the spirit to come first. Most of all you want the impossible: To borrow their French- or Italian-speaking brain for a few hundred pages, to see into the soul of Victor Hugo or Leo Tolstoy, however briefly, with as little mediation as possible, to be able to believe that this text was written in English all along, that you are drinking from the original source. When done well, this is a gift that can never be adequately appreciated or repaid.

The flip side of this weighty responsibility is an equally weighty disappointment if it’s handled poorly. Even in the best translations, I’ve stumbled on phrasings that are simply too clunky or awkward to be the best possible rendering, and it grates like a pebble in my shoe. I’ve read novels translated from Russian that persist in translating “bored” as “dull” – words that might seem interchangeable, until you read a sentence saying that someone is dull, when it’s obvious from context that what they really mean is that they’re bored. I’ve seen the word “explanation” used to describe what should have been translated as “argument” (characters having violent explanations in the next room, for example).

One of the most cringe-inducing examples of a mistranslation came to my attention recently when a character referenced the Latin motto “Sapere aude,” which was the Enlightenment-era rallying cry meaning “Dare to be wise” or “Dare to know.” Unfortunately, the translator rendered this as “To learn, listen,” mistakenly confusing the verbs audere (to dare) and audire (to listen). I only knew this was a mistake because of my rusty Latin. But other readers have no choice but to take that mistranslation at face value. Read more »

by Barry Goldman

There is a controversy about whether Section 3 of the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution disqualifies Donald Trump from serving as president. Different people have different opinions. Some people have different opinions at different times. But whatever their position on the question, everyone seems to agree that the question itself is a sensible one, and it has a correct answer. I don’t think so.

Let’s review.

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment says this:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

In August of 2023 law professors William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulson published a 126-page article in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review called “The Sweep and Force of Section Three.” Their conclusion was that Trump is ineligible.

Steven Calabresi, a professor at Northwestern University and one of the founders of the Federalist Society, read the article and posted on his blog:

Trump is ineligible to be on the ballot, and each of the 50 state secretaries of state has an obligation to print ballots without his name on them.

Subsequently, Michael Mukasey, Attorney General under George W. Bush, wrote a piece for the Wall Street Journal in which he reached the opposite conclusion. “Officer of the United States” he wrote, “refers only to appointed officials, not to elected ones.” Read more »

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Night Seagulls at Karachi Harbor, Dec 7, 2023.

Digital photograph.

by Ada Bronowski

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

The philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC, wrote in The Nicomachean Ethics that you cannot become good without practice. Even the ideal utterly good person whose every action is carried out at the right time for the right reason, has gone through a long process of trial and error; their ultimate victory over bad tendencies, precipitous judgement and external obstacles is a victory achieved through blood, sweat and tears. Aristotle’s promise is that the effort that engages both body and mind– if carried through with constancy and a bit of luck – will some day be sublimated into a way of being which will become both effortless and wholly constitutive of the moral agent. True enough, this ideal remains somewhat shrouded in the mist of a far-away horizon, but the path is paved, however arid and mountainous it may be. With the help of guides and maps, models and teachers, it is up to us to commit to the daunting effort.

Therein, of course, lies the rub. It is contained in two words: constancy and effort. And with them, the beginning and ending of morality.

Aristotle himself is rather pessimistic about his beautifully elaborated enterprise. He ends his Ethics – as explosive and powerful then as it is now (my goggle-eyed students confirm as much) – with a note to the effect that failing, as we almost all do, to become the ideal moral agent, through lack of time, will or stamina, we should rest content with obeying the laws of the land. They have been written by wiser people than us and especially are the fruit of a collaboration over generations of joint – if curtailed – effort towards the good. If constancy cannot be maintained over one’s own individual lifetime, a constancy over generations in the concern for constancy and the realisation of personal failure to live up to it, is an honourable compromise. If moral behaviour is a mirage some of us like to pursue more than others, a collective acknowledgement that we try and fail is the best we can do, building legal systems across political eras that make up for personal inconstance, laziness and lack of energy to improve. Read more »

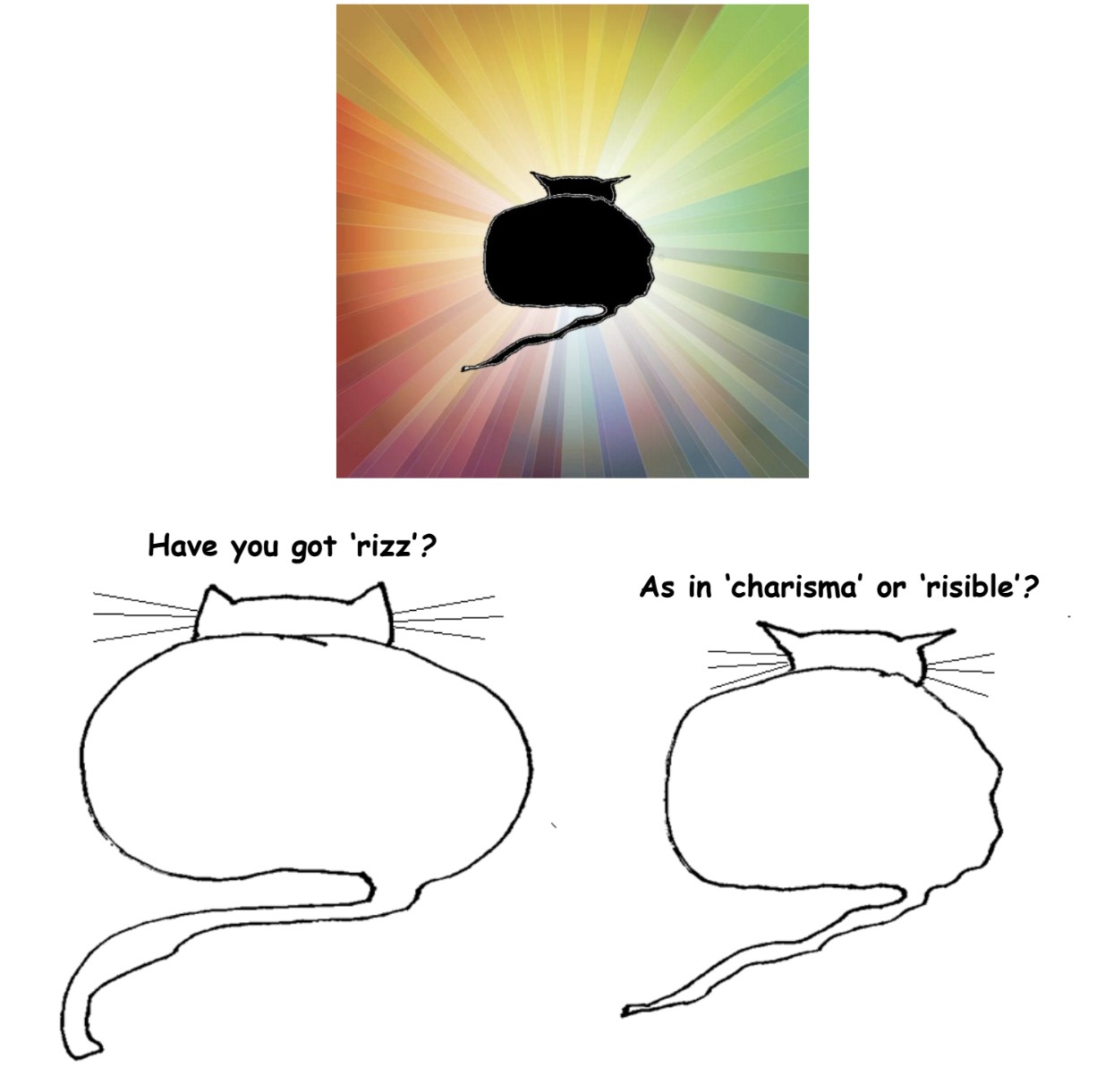

by Brooks Riley

by Mike O’Brien

This column was going to be about new issues in animal ethics and politics, following a slew of recent publications by Kristin Andrews, whose work I’ve been following for a few years. My big question about animal normativity, and the clues it may hold about the emergence of human capacities of moral reasoning, is whether animals display any signs of “meta-normative” capacities. In other words, whether they are able to reflect upon the norms they follow, and possibly rank or otherwise distinguish the generality and importance of these norms. So far, the answer is no, and one possible reason for this is that language may be a necessary tool for such abstract reflection. (Another reason is that it is very difficult to devise ways of investigating such capacities, or even to define them in ways that are not question-begging or overly anthropocentric). As no other animal species has yet demonstrated anything like human languages’ abilities of abstract representation and logical proposition, if moral reflection is dependent on language capacities then it may be unique to humans. (Yes, there are talking parrots and signing apes whose language abilities exceed what was hitherto believed possible, but they only achieved this by deliberate human tutelage, and the most capable of these animal individuals are not necessarily representative of species-wide capacities).

Curious whether proto-meta-ethical capacities may have been enabled in other species by proto-linguistic capacities, I wondered whether anyone has looked into pantomime in apes and other animals as a representational form of communication. Sure enough, many researchers have, with a great flourishing about a decade ago, including a paper by Dr Andrews that managed to escape my attention. But I’m not going to write about pantomime’s role in enabling proto-meta-ethical cognition in apes. Not in this column, anyway. Because, while navigating the many references and bookmarks of animal ethics publications littering my digital writing desk, I happened upon a paper about the ethical quandaries of owning a simulated human skin lampshade. How does one simply pass that over in silence? Read more »

by Derek Neal

Alberto Moravia’s 1960 novel Boredom begins and ends with the narrator, Dino, describing his relationship to external reality. He does this, in the first instance, by describing a drinking glass, and in the second instance, by describing a tree. Here are Dino’s thoughts in the prologue:

“The feeling of boredom originates for me in a sense of the absurdity of a reality which is insufficient, or anyhow unable, to convince me of its own effective existence. For example, I may be looking with some degree of attentiveness at a tumbler. As long as I say to myself that this tumbler is a glass or metal vessel made for the purpose of putting liquid into it and carrying it to one’s lips without upsetting it—as long as I am able to represent the tumbler to myself in a convincing manner—so long shall I feel that I have some sort of a relationship with it, a relationship close enough to make me believe in its existence and also, on a subordinate level, in my own. But once the tumbler withers away and loses its vitality in the manner I have described, or, in other words, reveals itself to me as something foreign, something with which I have no relationship, once it appears to me as an absurd object—then from that very absurdity springs boredom, which when all is said and done is simply a kind of incommunicability and the incapacity to disengage oneself from it. But this boredom, in turn, would not cause me to suffer so much if I did not know that, although I myself have no relationship with the tumbler, such a relationship might perhaps be possible, that is, because the tumbler exists in some unknown paradise in which objects do not for one moment cease to be objects. For me, therefore, boredom, is not only the inability to escape from myself but is also the consciousness that theoretically I might be able to disengage myself from it, thanks to a miracle of some sort.” [emphasis mine]

And here is Dino in the epilogue:

“As I have said, I spent hours gazing at the tree, to the great surprise of the nuns and the servants in the hospital, who said they had never seen a quieter patient than me. In reality I was not quiet, merely I was closely occupied with the only thing that truly interested me at that moment, the contemplation of the tree. I had no thoughts, I simply wondered when and how I had recognized the reality of the tree, had recognized, in other words, its existence as an object which was different from myself, had no relationship with me, and yet was there and could not be ignored. Evidently something had occurred just at the moment when I hurled myself off the road in my car; something which, to put it plainly, might be described as the collapse of an insupportable ambition. I now contemplated the tree with infinite complacency, as though to feel it different from myself and independent of me were the only thing that gave me pleasure…” [emphasis mine]

The change that occurs in the novel is one of consciousness. Read more »

by Joseph Shieber

In a recent talk at the Santa Fe Institute, the software engineer and tech startup founder Jason Crawford, who has in the last few years devoted his time to the Roots of Progress nonprofit, offered suggestions for developing institutions capable of fostering the acceleration of scientific progress.

Crawford framed the discussion around three questions: “When (if ever) has science accelerated in the past? Is it still accelerating now? And what can we learn from that?”

On the first question, whether science has accelerated in the past, Crawford offers an unequivocal “yes,” noting, in a whirlwind history, that

In the ancient and medieval world, we had only a handful of sciences: astronomy, geometry, some number theory, some optics, some anatomy

In the centuries after the Scientific Revolution (roughly 1500s–1700s), we got the heliocentric theory, the laws of motion, the theory of gravitation, the beginnings of chemistry, the discovery of the cell, better theories of optics

In the 1800s, things really got going, and we got electromagnetism, the atomic theory, the theory of evolution, the germ theory

In the 1900s things continued strong, with nuclear physics, quantum physics, relativity, molecular biology, and genetics

Though Crawford’s survey of the historical trends is brief, he is undoubtedly correct (and has much more to say about the historical record of progress on the blog for his nonprofit, The Roots of Progress). Just to underscore the point, it would be worth it to look at a few measures highlighting the acceleration of science. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

A proposition, like “it’s raining outside”, can either be true or false—it might be the case that it actually rains, or not. It is then seductive to think that somebody uttering such a proposition is doing nothing but making a factual claim, and in doing so, either tells the truth, or not. Furthermore, we might surmise that, in the case that the claim fails to actually hold, the utterer, proclaiming a falsehood, is lying. In doing so, however, we would be getting ahead of ourselves: there is both more to making a simple utterance than the mere proclamation of a fact, and to its veracity than lying or truth-telling. Let’s tackle these in turn.

First, when I tell you “it’s raining outside”, I not only make a claim about the world (that it is, in fact, raining outside), but also a claim about my own assertion: that it is, in fact, truthful; and thus, by extension, about myself: that I am a truth-teller. Consequently, you believing me does not just mean you believe something about the world, but also, that you believe something about my own relationship to truth, at least in this particular instance.

All of this means that simple facts about the world are never just simple facts about the world; inasmuch as they come to us indirectly, that is, not as immediately present in our own experience, they are elements of a complex web of beliefs and attitudes. Believing me to be an inveterate liar, you might well rather be inclined to believe that it’s all sunshine outside when you hear me blathering on about the drizzle. If you happen to know I’ve spent the last hour tinkering away in the cellar, you might not attach any particular value to my claim, believing me to be ignorant on the matter. Your judgment regarding the meta-claim of my assertion’s truthfulness affects your belief in its content: the world-picture you create based upon it varies with your assessment of my stance towards truth. Read more »

by Terese Svoboda

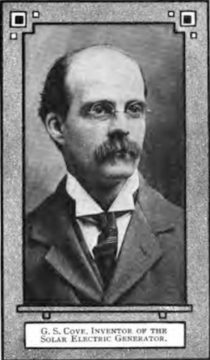

The year 1909 was the first time George H. Cove vanished. He claimed he was kidnapped and threatened with death if he continued developing his patent on solar panels. One story has it that an investor arranged the kidnapping to discredit him, and that instead of death, he was offered a furnished house and $25,000 (almost a million dollars in today’s money) if he would cease promotion of his solar panels. Newspapers went crazy and he was subsequently accused of arranging the kidnapping as a publicity stunt. But Cove already had plenty of publicity, one would say too much, newspapers lauding his efforts and investors pouring money into his work.

The police dismissed the kidnapping as a hoax. Were they paid off? His rivals, Edison, Westinghouse, and Standard Oil, were notorious in stamping out competition. All three were known to use extreme measures to protect their market share. Cove had been fronted (framed?) by Elmer Burlingame, who issued stock he did not own in Cove’s Sun Electric Generator Company. When this was revealed, investors went sour. In 1911, after raising $160 million in today’s money, his company declared bankruptcy. Cove was arrested for stock fraud and went to jail for a year. Perhaps he should have gone into stealth mode.

“Given two days’ sun, it will store sufficient electrical energy to light an ordinary house for a week” was Cove’s pitch.While his solar panels didn’t generate much electricity in comparison with Westinghouse and Edison’s inventions, he’d invented something much more important, the photovoltaic generator, that is, a way to get electricity directly from the sun. He did not understand how the solar panel worked, but neither did anybody else at the time. This technology would not be investigated again until the 1950s at Bell Labs, and then with silicon rather than the simpler version that Cove stumbled on. Read more »

by Michael Liss

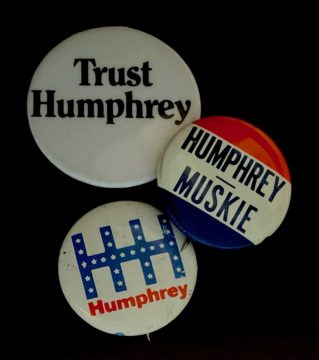

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

The broken-down jalopy that was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign wheezed its way out of Chicago and headed…anywhere but there. The Convention was an utter disaster. The only “bump” in the polls was a shove backwards, and Humphrey seemed to have nothing with which to shove back. He had no coherent message on the biggest issue of the day—Vietnam. He was working for an absolutely impossible boss, LBJ, who demanded complete loyalty and delighted in humiliating him. His campaign was broke…it literally didn’t have enough money to pay for orders of Humphrey buttons.

It didn’t end there. He was fighting the electoral realignment centrifuge that was ripping apart the New Deal Democratic coalition. The formerly Solid South was more than 20 years into its secession. The Party’s hold on the blue-collar family was being tested by the cultural appeal of George Wallace. Suburbanites were worried about the violence in big cities and wanted leadership to do something about it. In theory, they were moderates, supporters of the Civil Rights movement. In practice, many applied a NIMBY approach. The youth vote was inextricably connected to the anti-war vote; the war was inextricably connected to Johnson; and LBJ was inextricably connected to Humphrey. Read more »