This article has three main sections. Immediately following the image (created by ChatGPT) is an article by me, ChatGPT 5.2 and Claude 4.5: The Grammar of Truth: What Language Models Reveal About Language Itself. Claude came up with that title. After that there’s a much shorter section in which I explain how the three of us created that article. I conclude by I taking the question of how to properly credit such writing. That issue is one aspect of the institutionalization discussed in what I will call the “included article.”

The Grammar of Truth: What Language Models Reveal About Language Itself

William Benzon, assisted by ChatGPT 5.2 and Claude 4.5

In the 1980s, when the linguist Daniel Everett went to live with the Pirahã people of the Amazon, he had a mission: to translate the Bible into their language and convert them to Christianity. What he discovered, however, was something he hadn’t anticipated. The Pirahã didn’t exactly reject his religious message. They just couldn’t take him seriously.

The problem, as Everett eventually came to understand, was grammatical. Pirahã requires speakers to mark the source of their knowledge. When you make a claim about something, you have to indicate whether you witnessed it directly, heard it from someone else, or learned it in a dream. This isn’t an optional rhetorical flourish. It’s as obligatory as verb tense in English. Everett had not seen Jesus himself. He knew no one who had. And he wasn’t reporting a dream. By the grammatical standards of Pirahã discourse, he had no business speaking at all.

This grammatical feature—what linguists call evidentiality—turns out to be far more than a curiosity about an Amazonian language. It opens a window onto something fundamental about how human societies organize knowledge. And, as we’ll see, it ultimately reveals why the emergence of large language models like ChatGPT represents not just a technological achievement but a conceptual rupture that forces us to rethink what language itself is. Read more »

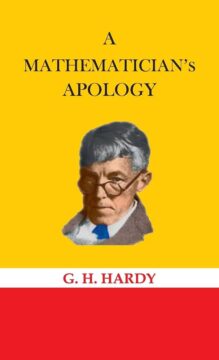

I have put off reading G.H. Hardy’s Mathematician’s Apology (1940) to the end for too long. Now that I have, I can say with conviction that if you ever find yourself needing to justify why people should learn at least some mathematics, then this is the text to avoid, and Hardy provides the arguments you should stay away from furthest. And yet, it grew on me as an honest presentation of Hardy’s perspective on why anything is worth doing.

I have put off reading G.H. Hardy’s Mathematician’s Apology (1940) to the end for too long. Now that I have, I can say with conviction that if you ever find yourself needing to justify why people should learn at least some mathematics, then this is the text to avoid, and Hardy provides the arguments you should stay away from furthest. And yet, it grew on me as an honest presentation of Hardy’s perspective on why anything is worth doing. Sughra Raza. Blood. August 2024.

Sughra Raza. Blood. August 2024.

a prickly pine’s upon one nub,

a prickly pine’s upon one nub,

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

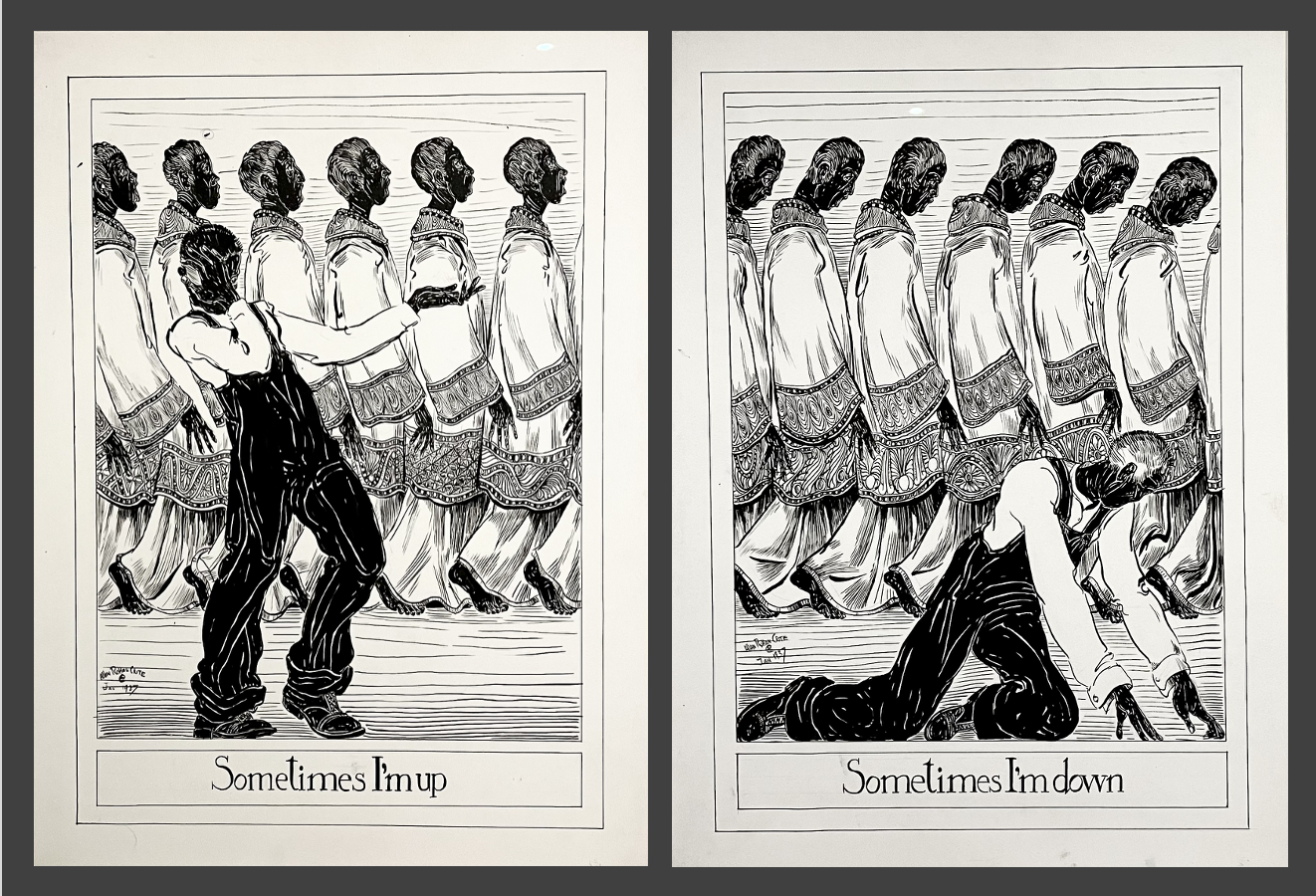

Allan Rohan Crite. Sometimes I’m Up, Sometimes I’m Down. Illustration for Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven (Cambridge, Mass., 1948),” 1937.

Allan Rohan Crite. Sometimes I’m Up, Sometimes I’m Down. Illustration for Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven (Cambridge, Mass., 1948),” 1937.