by Judith Goudsmit and Asad Raza

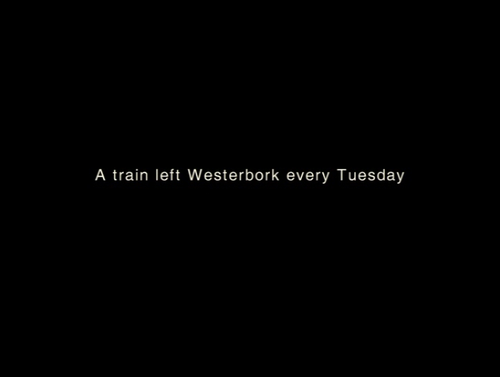

Respite consists mostly of black-and-white film shot at Westerbork, a Dutch refugee camp established in 1939 for those fleeing Germany. In 1942, after the occupation of Holland, its function was reversed by the Nazis and it became a 'transit camp.' In 1944, the camp commander commissioned a film, shot by a photographer, Rudolph Breslauer; this is the footage used in Respite. It shows inmates processing mechanical parts, doing aerobics, mounting stage productions, and other activities. It also shows inmates being loaded onto trains. Before the film could be completed, its subjects, as well as Breslauer, were transferred to Auschwitz and killed. Farocki's Respite, like the original images, contains no sound. His changes to the archival footage are very simple: he edits it and intersperses black title cards on which short texts, usually one sentence, appear.

(All film stills courtesy of Greene Naftali Gallery, New York)

Judith Goudsmit: It's interesting how the texts Farocki provides us with evolve over the course of the film. First, we view the images with short explanations of what we are seeing. Then, as if he is reevaluating his previous interpretations, he repeats certain images with different, more personal texts, pointing out certain details, or emphasizing one aspect of the image. Watching it, I felt like I was being tested, as if he was asking what would be more effective, what would be more shocking, provoking, sad, etc. Maybe because I grew up hearing so many stories about Westerbork, and the Holocaust generally–almost every successful Dutch novel is about the Holocaust or its aftermath–I have become so familiar with the way people tell these stories that these personal notes Farocki gives us almost seem to play with clichéd or contrived notions of the Holocaust and its impact. Also, the images just seem plain joyous at first: genuine fun, jumping around in a circle. Later, with Farocki's comments, this 'fun' gets macabre undertones. I think he is questioning whether we can look at these images without the knowledge we have now, without their context of death. Is it ever possible to look at things just for what they are? Of course he is questioning a lot more, but I'm rambling and just had a phone fight with my mother. What do you think?

Asad Raza: I think Respite is a very honest film, because it admits a really basic truth: not only can we not look at things for what they are, we can't even know what they are. Respite doesn't pose, as most documentaries do, as an objective account of historical reality; it's more like a meditation on its source material. As you said, some of its archival images seem very incongruous to the tragic destiny of Westerbork–people dancing and jumping and smiling. The title cards tell us these images are rarely shown, perhaps because they aren't obviously or viscerally terrible. They aren't symbolic enough of the historical “meaning” of Westerbork. Yet the fleeting smiles of the camp's inmates are possibly more crushing than the standard Holocaust-documentary shot of hills of corpses. Dead bodies are ultimately objects; a woman leading a dance class, who we know will soon be murdered–this is sickness and tragedy. And the film lets us ponder this footage without the distraction of music or other added elements. It doesn't tell us how to feel too directly, which allows our own reactions to emerge all the more powerfully. This way, the film respects the basic strangeness, or unknowability, of these moving images, instead of pretending that they record a reality we already know how to interpret.

Read more »