by Mary Hrovat

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

Every October there’s a huge book fair in my town, where used books donated by the community are put up for sale in a large hall at the fairgrounds. It’s no exaggeration to say that it’s a high point of my year.

When I walk in and see table after table laden with books and inhale the unmistakable smell of the printed page, I almost always get a sense of the richness of the world and a feeling of optimism about my opportunities for learning about it. Even though I know that in addition to many treasures, the tables also hold things like the 1979 edition of What Color Is Your Parachute?, I still feel the thrill. It reminds me of when I was a teenager and didn’t realize how finite my life is. I was in love with history in particular, and with archaeology, with music and art and astronomy. But I also wanted to learn how to do things: draw, paint, play chess, grow vegetables. Growing up in a family where my mother was often too busy and my father was too distant to teach any of us much beyond the fundamentals of their religion, I thought books could teach me those things too.

The layout at the book fair is always pretty much the same. There are certain tables I visit first, and some I rarely check. I usually have a few specific titles or subject areas in mind: There’s an author I’ve become interested in, or a historical period I’m reading about. I always look for Paul Theroux on the Travel table. Over the better part of a decade, I slowly assembled all eleven volumes of Will and Ariel Durant’s The Story of Civilization and the Norton Anthologies of English and American literature. Read more »

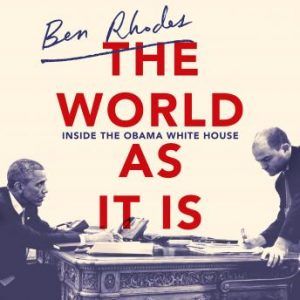

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.

As the first African American president of the United States (US), Barack Obama is a uniquely historical personality. Each of us has our opinions, or will formulate opinions, as to the success or limitations of his eight years in office as a Democratic president from 2009-2017, and as to the person who is Obama. Helping us in the formulation of our views on Obama and his presidency, is Ben Rhodes book, The World As It Is: Inside the Obama White House.  One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily.

One of the most simple, elegant and powerful formulations of the conflict between science and religion is the following bit of reasoning. ‘Faith’ is belief in the absence of evidence; science demands that beliefs are always grounded in evidence. Therefore, the two are mutually exclusive. This is an oft-repeated argument by modern atheists, and it connects different aspects of what is usually called the ‘Conflict Thesis’: the idea that science and religion are opposed to each other not just now, but always and necessarily. In the Mood for Love

In the Mood for Love

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.”

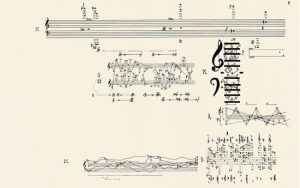

One of the things I love about sports is they’re a low-stakes environment in which to practice high-stakes skills. For most people, most of the time, the results of a sporting match don’t affect the long-term quality of their lives. This is what I mean by “low-stakes.” In the grand scheme and scope of our lives, the outcomes of games rarely matter. Which is what makes sports such a great place to practice skills that really can and do impact our lives for the better. This is what I mean by “high-stakes.” In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

In the fall of 1970, I brought a Bundy tenor saxophone home from school. I was nine and in Mrs Farrar’s 5th grade class. To celebrate, my father slid an LP called “Soultrane”out of a blue and white cardboard jacket. The first sounds from the record player’s single speaker: a muscular folk song with rippling connective tissue that quickly spun free into endless cascades. Dad explained that it was my new horn, in the hands of John Coltrane. I didn’t know his name and nothing that day seemed possible, anyway.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.

Recently, CNN sent their reporter to cover yet another Trump rally (in Pennsylvania), but this time reporter Gary Tuchman was assigned the more specific task of interviewing Trump supporters who were carrying signs or large cardboard cut-outs of the letter “Q” and wearing T-shirts proclaiming “We are Q”.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights.

In the 1960s, in the sleepy little city of Sialkot, almost in no-man’s land between India and Pakistan and of little significance except for its large cantonment and its factories of surgical instruments and sports goods, there were two cinema houses, all within a mile of our house, No. 3 Kutchery Road. Well three to be exact, the third being an improvisation involving two tree trunks with a white sheet slung between them at the Services club and only on Saturday nights. Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

Would I rather go deaf or blind? Every once in a while, I come back to this question in some version or another. Say I had to choose which sense I’d lose in my old age, which would it be? I always give myself, unequivocally, the same answer: I’d rather go blind. I’d rather my world go darker than quieter. I imagine it as a choice between seeing the world and communicating with it; in this hypothetical, communication with the world is all-encompassing, its loss more devastating than the loss of sight. It is perhaps clear from the mere fact that I pose this question that I do not live with a disability involving the senses. Individuals who are vision- or hearing-impaired would have an entirely different take on this question and on the issues I raise below, but hopefully what I write here will go beyond stating my own prejudices.

The German philosopher

The German philosopher  The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?

The idea of ‘good corporate citizenship’ has become popular recently among business ethicists and corporate leaders. You may have noticed its appearance on corporate websites and CEO speeches. But what does it mean and does it matter? Is it any more than a new species of public relations flimflam to set beside terms like ‘corporate social responsibility’ and the ‘triple bottom line’? Is it just a metaphor?