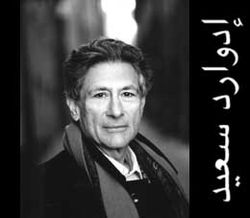

In honor of the sixth death anniversary of the great literary critic and distinguished Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, I am linking back to a column published by Asad Raza (September 26, 2005) on this blog:

Optimism of the Will

By Asad Raza

The first time I saw Edward Said, in 1993, I was an undergraduate studying literature at Johns Hopkins, where he had come to give a lecture. An extremely pretentious young person, I arrived in the large hall (much larger than the halls in which other visiting literature professors spoke) with a mixture of awe and, I'm afraid to say, condescension. This was born of the immature idea that the author of Orientalism had ceased to occupy the leading edge of the field, postcolonial studies, which his work had called into being. At that time, the deconstructionist Homi Bhabha and the Marxist Aijaz Ahmad were publishing revisions of (and, in the case of Ahmad, ad hominem attacks on) Said's work, and Said himself seemed to be retreating from “theory” back to some vaguely unfashionable (so it seemed to me) version of humanism.

There are interludes in which a thinker's work, no matter how enabling or revolutionizing, are liable to attack, to labels such as “dated” or “conservative,” from more insecure minds. In this case, the actual presence of Said destroyed those illusions utterly. Seated on a dais at a baby-grand piano, he delivered an early version of his reading of “lateness,” on the late work of master figures such as Beethoven and Adorno. In a typical stroke, Said's use of Beethoven's late work as one example, and then Adorno's late work on Beethoven as a second example, highlighted the mutual relationship between artist and critic, each dialectically enabling the other's practice. The further implication, of course, that Said himself was a master critic entering such a late period (he had recently been diagnosed with cancer) was as palpably obvious as the idea that Said would say such a thing aloud was preposterous. And on top of it all, he played the extracts from Beethoven he discussed for us, with the grace of a concert pianist (which he was). I left the auditorium enthralled.

Within the next year, I was lucky enough to be invited to dinner with Said by my aunt Azra, who was one of the doctors treating him for leukemia. Seated next to him, I challenged him on several subjects, with the insufferable intellectual arrogance of youth. His responses were sometimes pithy and generous, sometimes irritated and indignant. On Aijaz Ahmad, who had been attacking him mercilessly and unfairly, he simply muttered, “What an asshole.” How refreshing! When I asked him why we continued to read nineteenth-century English novels, if they repressed the great human suffering that underwrote European colonial wealth, he gave the eminently sensible answer, “Because they're great books.” At another dinner, at a Manhattan temple of haute cuisine where he addressed the waiters in French, I complained that the restaurant's aspirations to a kind of gastronomic modernism were at odds with their old-fashioned, country club-ish “jacket required” policy. He raised an eyebrow at me and dryly remarked, “I hadn't even noticed the internal contradiction.” Score one for the kid.

In 2003, as a graduate student in English at NYU, I rode the subway up to Columbia each week for a seminar with Said, which turned out to be the last one he taught. Wan and bearded, Said would walk in late with a bottle of San Pellegrino in hand and proceed to hold forth, off the cuff, about an oceanic array of subjects relating to the European novel (Don Quixote, Gulliver's Travels, Sentimental Education, Great Expectations, Lord Jim, etc.), alternately edifying and terrifying his audience. He had an exasperation about him that demanded one to know more, to speak more clearly, to learn more deeply in order to please him. Some found the constant harangues too traumatic for their delicate sensibilities; I loved to have found a teacher who simply did not accept less than excellence. It was a supremely motivating, frightening, vitalizing experience. In a class on Robinson Crusoe, a fellow student became confused about the various strands of eighteenth-century non-conformist Protestantism, prompting Said to irritatedly draw a complex chart of the relations between Dissenters, Puritans, Anglicans, etc. Similar demonstrations of the sheer reserves of his knowledge occurred on the subjects of the revolutions of 1848, the history of Spanish, and the tortuous philosophical subtleties of Georg Lukacs' Theory of the Novel, among other things. Said had a whole theory of the place of nephews in literature (not the real son, but the true inheritant), and he made himself his students' challenging, agresssive, truth-telling, loving uncle.