Old Berliners in the media complained that twenty years ago even the Wetter was better. In 1989, the stars apparently shone down on revelers dancing on the Brandenburger Tor as they tore the wall to pieces. And the next day, when the East Berliners chugged onto the Kurfürstendamm—then the main drag in West Berlin—in their gas-guzzling Trabbies, the sky was blue. Of course, when I flip through photos from the famous day, the newly reunited Berlin of twenty years ago looks as grey as grey can be. Helmut Kohl (the then Chancellor) and Willy Brandt (the Social Democratic Party hero who partially reconciled East and West through his Ostpolitik) stood on a balcony above the Schöneberger Rathaus, in the midst of mist and rain, in front of thousands of people. Yesterday, the sky was perhaps even more unrelenting. Rain fell on a hundred thousand people as they elbowed each other for a view of the big screens that relayed images of the Tor (next to which a puffy Bon Jovi bawled out something about freedom). Although the ceremony seemed designed to rev Germans up, all around me I could hear a burble of other languages. While a kitschy German boy band performed a song about freedom, Spanish students enthusiastically noted how German the whole thing seemed. Americans ordered pizzas to go at a stand nearby; clumps of French tourists debated where to party after the ceremony.

more from Charles McPhedran at n+1 here.

Four hundred years ago, in 1609, Galileo made the first observations with the telescope. The discoveries come out, primary the one that made Galileo promoting the Copernican theory of the Earth’s rotation around the Sun and then to replacing the doctrine concerning the position and the role of the Earth in the space, have been revolutionary non only in terms of scientific development but also in terms of social, technological and economic development, although the strong cultural and religious opposition. Galileo, named as “heretic” by the Catholic Church, was obliged to abjure. Scientific innovation and its dissemination have always played a determinant role in the cultural development of society: but, although the knowledge development is a process that could not be stopped, we can not say the same for what concerns its spread, or better, its accessibility, that is one the main means, if not “the mean”, of democracy. Nevertheless, thanks to the introduction of new technologies and then, thanks to the scientific evolution itself, the transfer and the spread of knowledge have been characterized by an ever greater acceleration. “To know” means “to be able to make a choice”: the word “heresy” originates from Greek and it means “choice”. Then, originally, “heretic” was the person who was able to consider the different options before choosing one. In 2009, European year of Creativity and Innovation, and in our society, defined as the “knowledge society”, at a distance of four hundred years from Galileo’s “heresy”, there is any hope to be “authentically heretic”?

more from Emanuela Scridel at Reset here.

I’ve joined them in my mind somehow, these two, yet Wallace tilted against Updike in the pages of The New York Observer some years ago (and I tilted with him, writing a parallel piece that claimed that the Master was too prolix, too ready to come forward into print with whatever his pen produced). They represented different, in some ways opposing worlds. Wallace was, in a core part of his being, an unassimilated subversive, and what he subverted, over and over, in his exacerbated scenarios, his outlaw fugues, was the vast entrenched order, the what is that Updike chronicled with calm Flemish exactitude. Updike celebrated an assumption about reality that Wallace was in some defining way at odds with. To call it a father/son dynamic would be simplistic, of course, but there are certain elements of that conventional agon, including the son’s will not just to repudiate but to outdo the father. Considering the divergence in their aesthetics—Wallace’s complete lack of interest in the realism that takes surfaces as the outer manifestation of interior forces—the field of engagement would have to be the how as opposed to the what. Which is to say the how of language, style: the sentence. Is it farfetched to think of Wallace’s prose pitching itself in sustained defiance against the philosophical ground of Updike’s, its lightly ironized acceptance of things as they are? The bemused Updike smile endorses a reality, an outlook, that Wallace could not fit himself to, a failure that was bound up, I suspect, with his deepest suffering. Fathers and sons, but also order and chaos.

more from Sven Birkerts at AGNI here.

It is commonplace, 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, to hear the events of that time described as miraculous, a dream come true, something one couldn’t have imagined even a couple of months beforehand. Free elections in Poland with Lech Walesa as president: who would have thought it possible? But an even greater miracle took place only a couple of years later: free democratic elections returned the ex-Communists to power, Walesa was marginalised and much less popular than General Jaruzelski himself. This reversal is usually explained in terms of the ‘immature’ expectations of the people, who simply didn’t have a realistic image of capitalism: they wanted to have their cake and eat it, they wanted capitalist-democratic freedom and material abundance without having to adapt to life in a ‘risk society’ – i.e. without losing the security and stability (more or less) guaranteed by the Communist regimes. When the sublime mist of the ‘velvet revolution’ had been dispelled by the new democratic-capitalist reality, people reacted in one of three ways: with nostalgia for the ‘good old days’ of Communism; by embracing right-wing nationalist populism; with belated anti-Communist paranoia.

more from Slavoj Žižek at the LRB here.

Thursday, November 12, 2009

Seymour M. Hersh in The New Yorker:

In the tumultuous days leading up to the Pakistan Army’s ground offensive in the tribal area of South Waziristan, which began on October 17th, the Pakistani Taliban attacked what should have been some of the country’s best-guarded targets. In the most brazen strike, ten gunmen penetrated the Army’s main headquarters, in Rawalpindi, instigating a twenty-two-hour standoff that left twenty-three dead and the military thoroughly embarrassed. The terrorists had been dressed in Army uniforms. There were also attacks on police installations in Peshawar and Lahore, and, once the offensive began, an Army general was shot dead by gunmen on motorcycles on the streets of Islamabad, the capital. The assassins clearly had advance knowledge of the general’s route, indicating that they had contacts and allies inside the security forces.

In the tumultuous days leading up to the Pakistan Army’s ground offensive in the tribal area of South Waziristan, which began on October 17th, the Pakistani Taliban attacked what should have been some of the country’s best-guarded targets. In the most brazen strike, ten gunmen penetrated the Army’s main headquarters, in Rawalpindi, instigating a twenty-two-hour standoff that left twenty-three dead and the military thoroughly embarrassed. The terrorists had been dressed in Army uniforms. There were also attacks on police installations in Peshawar and Lahore, and, once the offensive began, an Army general was shot dead by gunmen on motorcycles on the streets of Islamabad, the capital. The assassins clearly had advance knowledge of the general’s route, indicating that they had contacts and allies inside the security forces.

Pakistan has been a nuclear power for two decades, and has an estimated eighty to a hundred warheads, scattered in facilities around the country. The success of the latest attacks raised an obvious question: Are the bombs safe? Asked this question the day after the Rawalpindi raid, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said, “We have confidence in the Pakistani government and the military’s control over nuclear weapons.” Clinton—whose own visit to Pakistan, two weeks later, would be disrupted by more terrorist bombs—added that, despite the attacks by the Taliban, “we see no evidence that they are going to take over the state.”

More here. (Note: Thanks to Zeba Hyder.)

From Science:

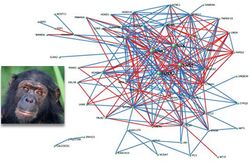

For the first time, scientists have compared a vast network of human genes responsible for speech and language with an analogous network in chimpanzees. The findings help shed light on how we moved beyond hoots and grunts to develop vast vocabularies, syntax, and grammar.

For the first time, scientists have compared a vast network of human genes responsible for speech and language with an analogous network in chimpanzees. The findings help shed light on how we moved beyond hoots and grunts to develop vast vocabularies, syntax, and grammar.

The centerpiece of the study is FOXP2, a so-called transcription factor that turns other genes on and off. The gene rose to fame in 2001 when researchers showed that a mutant form of it caused an inherited speech and language problem in three generations of the “KE family” in England. The following year, researchers showed that normal FOXP2 differed by only two amino acids–the building blocks of proteins–between humans and chimpanzees. Analyzing more ancestral species, they further showed that the gene was highly conserved all the way up to chimps, suggesting that it played a prominent role in our unique ability to communicate complex thoughts.

More here.

Frank Stella is an old (20th century) master of abstract art, Martha Russo is a new (21st century) master of abstract art, but they both have something in common: the belief that an abstract work of art has no limits — that its forms spill and spread into the environment, suggesting its inner abstract character. The idea of “boundless abstraction” first surfaced in the water lily murals of Monet — for Greenberg they were abstract in all but name, and set the precedent for Pollock’s all-over mural paintings — and was extended by Kandinsky, however hesitantly, in his early works, particularly the famous First Abstract Watercolor (1911, scholars now say 1912 or 1913). There the eccentric continuum of petite color and line perceptions moves beyond the technical boundaries of the work, suggesting an infinite flux of uncontainable visual sensations. Pollock’s implicitly boundless mural abstractions are the climactic statement of “abstraction as total environment,” correlate with the idea of the “environment as totally abstract.” Abstraction came to dominate thinking about the environment as well as art, and the triumph of abstraction signaled by such opposed movements as Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism confirmed that it had become a generalized mode of perception and cognition: only when art and the environment were perceived and understood in abstract terms was their presence convincing.

more from Donald Kuspit at artnet here.

The German philosopher Walter Benjamin had the curious notion that we could change the past. For most of us, the past is fixed while the future is open. Benjamin thought that the past could be transformed by what we do in the present. Not literally transformed, of course, since the one sure thing about the past is that it does not exist. There is no way in which we can retrospectively erase the Treaty of Vienna or the Great Irish Famine. It is a peculiar feature of human actions that, once performed, they can never be recuperated. What is true of the past will always be true of it. Napoleon will be squat and Einstein shock-haired to the end of time. Nothing in the future can alter the fact that Benjamin himself, a devout Jew, committed suicide on the Franco-Spanish border in 1940 as he was about to be handed over to the Gestapo. Short of some literal resurrection, the countless generations of men and women who have toiled and suffered for the benefit of the minority – the story of human history to date, in fact – can never be recompensed for their wretched plight.

more from Terry Eagleton at The New Statesman here.

For many people, up to the end of the seventeenth century, dragons and fairies were part of everyday life. Dragon skins hung in some parish churches and ploughing regularly turned up elf arrows, little-worked flints of great delicacy. The geographer Sir Robert Sibbald included several examples in his great account of the natural history of Scotland, Scotia Illustrata, published in 1684. At that date “Britain” was, by contrast, a largely mythical concept, a political allegory useful to the Stuart monarchy. After 1707, the situation was reversed. With the Act of Union, Britain became a legal entity, while dragons and fairies had begun their slow fade into myth. Writing in 1699, the naturalist Edward Lhuyd, to whom Sibbald had just shown off his collection of elf arrows, had no hesitation in dismissing them as man-made, “just the same as the chip’d flints the natives of New England use to head their arrows with”. The shift of belief was seen by most historians as a sign of social and intellectual progress, a notion which in itself, as John Aubrey observed, represented a change in attitudes towards the past.

more from Rosemary Hill at the TLS here.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Why baby Jesus? Research confirms there were upwards of 157 hotel-cum-stables in Bethlehem that night, with estimated 97 percent occupancy levels. So why did that star shine so brightly over his? Imagine that I were to ask you to dress up as a baby and lie in a manger. Would you attract a comparable crowd of shepherds plus livestock and anything upwards of three kings from the East? In a hugely influential 2004 experiment at the University of Colorado at Bollocks Falls, Professor Sanjiv Sanjive and his team asked 323 volunteers to wrap themselves in swaddling clothes and spend the night in a stable, lying in a manger. Logic would dictate that at least one of them would be visited by shepherds, wise men, or kings from the East, right? Wrong.

more from Craig Brown at Vanity Fair here.

Zach Baron in The Village Voice:

Those who have been paying attention to Zadie Smith since her White Teeth debut likely already know about her affinities for E.M. Forster, Lil Wayne, George Eliot, Kafka, and Fawlty Towers. She's one of probably three working writers capable of smuggling a riff on the perils of “keeping it real” into The New York Review of Books. And who else is near versatile enough to credibly compare the oratorical tics of novelist-philosophers Tom McCarthy and Simon Critchley to those of Morrissey, circa the Smiths? Like her rhetorical comrade Barack Obama, Smith doesn't just speak for her variegated experience as a 34-year-old critic, rap fan, global citizen, comedy connoisseur, cinema dilettante, black woman, reluctant professor, and, lest we forget, virtuoso novelist—she speaks the experience itself.

Those who have been paying attention to Zadie Smith since her White Teeth debut likely already know about her affinities for E.M. Forster, Lil Wayne, George Eliot, Kafka, and Fawlty Towers. She's one of probably three working writers capable of smuggling a riff on the perils of “keeping it real” into The New York Review of Books. And who else is near versatile enough to credibly compare the oratorical tics of novelist-philosophers Tom McCarthy and Simon Critchley to those of Morrissey, circa the Smiths? Like her rhetorical comrade Barack Obama, Smith doesn't just speak for her variegated experience as a 34-year-old critic, rap fan, global citizen, comedy connoisseur, cinema dilettante, black woman, reluctant professor, and, lest we forget, virtuoso novelist—she speaks the experience itself.

The last novel Smith published, On Beauty, made explicit homage to Forster and gave a main character the name Zora, as in Neale Hurston. And so in Changing My Mind, Smith's new book of occasional essays, both writers get critical evaluations. In an appraisal of her own first novel, Smith once copped to some “inspired thieving” from Nabokov—he, too, receives extended consideration in Changing My Mind. “This book was written without my knowledge,” the author admits in the foreword, meaning it was written piecemeal, unintentionally. In a drawer somewhere still sits “a solemn, theoretical book about writing,” entitled Fail Better. The next novel, which would be Smith's fourth, remains unfinished. This is what was written instead, along the way.

More here.

Karl Sigmund in American Scientist:

Humans are social animals, and so were their ancestors, for millions of years before the first campfires lighted the night. But only recently have humans come to understand the mathematics of social interactions. The mathematician John von Neumann and the economist Oskar Morgenstern were the first to tackle the subject, in a book they were planning to call A General Theory of Rational Behavior. By the time it was published in 1944, they had changed the title to Game Theory and Economic Behavior, an inspired move. The book postulated, as did all follow-up texts on game theory for generations, that players are rational—that they can figure out the payoff of all possible moves and always choose the most favorable one.

Humans are social animals, and so were their ancestors, for millions of years before the first campfires lighted the night. But only recently have humans come to understand the mathematics of social interactions. The mathematician John von Neumann and the economist Oskar Morgenstern were the first to tackle the subject, in a book they were planning to call A General Theory of Rational Behavior. By the time it was published in 1944, they had changed the title to Game Theory and Economic Behavior, an inspired move. The book postulated, as did all follow-up texts on game theory for generations, that players are rational—that they can figure out the payoff of all possible moves and always choose the most favorable one.

Three decades later, game theory got a new lease on life through the work of biologists William D. Hamilton and John Maynard Smith, who used it to analyze biological interactions, such as fights between members of the same species or parental investment in offspring. This new “evolutionary game theory” was no longer based on axioms of rationality. Anatol Rapoport, one of the pillars of classical game theory, characterized it as “game theory without rationality.” Herbert Gintis was among the first economists attracted by the new field, and when, 10 years ago, I wrote a review of his textbook Game Theory Evolving, I described it as “testimony of the conversion of an economist.” Gintis has not recanted in the meantime—indeed, a second edition of that book just appeared. But a new companion volume, titled The Bounds of Reason, shows that he certainly has not forgotten his upbringing in the orthodox vein.

More here.

Kishore Mahbubani in the New York Times:

The 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall has just been celebrated. For many, that momentous event marked the so-called end of history and the final victory of the West.

The 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall has just been celebrated. For many, that momentous event marked the so-called end of history and the final victory of the West.

This week, Barack Obama, the first black president of the once-triumphant superpower in that Cold War contest, heads to Beijing to meet America’s bankers — the Chinese Communist government — a prospect undreamt of 20 years ago. Surely, this twist of the times is a good point of departure for taking stock of just where history has gone during these past two decades.

Let me begin with an extreme and provocative point to get the argument going: Francis Fukuyama’s famous essay “The End of History” may have done some serious brain damage to Western minds in the 1990s and beyond.

Mr. Fukuyama should not be blamed for this brain damage. He wrote a subtle, sophisticated and nuanced essay. However, few Western intellectuals read the essay in its entirety. Instead, the only message they took away were two phrases: namely “the end of history” equals “the triumph of the West.”

Western hubris was thick in the air then. I experienced it. For example, in 1991 I heard a senior Belgian official, speaking on behalf of Europe, tell a group of Asians, “The Cold War has ended. There are only two superpowers left: the United States and Europe.”

More here. [Thanks to Kris Kotarski.]

Wan Chu's Wife In Bed

Wan Chu, my adoring husband,

has returned from another trip

selling trinkets in the provinces.

He pulls off his lavender shirt

as I lie naked in our bed,

waiting for him. He tells me

I am the only woman he'll ever love.

He may wander from one side of China

to the other, but his heart

will always stay with me.

His face glows in the lamplight

with the sincerity of a boy

when I lower the satin sheet

to let him see my breasts.

Outside, it begins to rain

on the cherry trees

he planted with our son,

and when he enters me with a sigh,

the storm begins in earnest,

shaking our little house.

Afterwards, I stroke his back

until he falls asleep.

I'd love to stay awake all night

listening to the rain,

but I should sleep, too.

Tomorrow Wan Chu will be

a hundred miles away

and I will be awake all night

in the arms of Wang Chen,

the tailor from Ming Pao,

the tiny village down the river.

By Richard Jones

from The Quarterly, 1990

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, NY

Leipzig is a very good place from which to approach eastern Europe.[1] For those coming from further west the city is a halfway stop, even if the train connections are not as good as perhaps one might have hoped twenty years ago, when the Iron Curtain disappeared. Leipzig is connected to eastern Europe and its history by a thousand threads – one need only think of the foundation of its university, or of the long-distance trade routes. At their intersection arose the trade fair, which during the Cold War became a sluice chamber, a contact yard between the hemispheres that opened for a moment every year. And consider the renewed interest in eastern Europe in Leipzig today, its book fair and its academic and research institutions, which have become trademarks of the city. So why should anyone from outside take the trouble of essaying an approach to the East in a place which is already so close – geographically, culturally, and academically? All the more so, since the topic of this conference is general and does not imply a question to which one must provide an answer. The chain of ideas “History of memory, places of memory, strata of memory” is more a set of associations and is intended to delimit an area.

more from Karl Schlögel at Eurozine here.

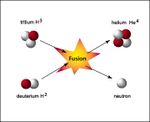

Fusion has been the Holy Grail of energy since long before anyone ever worried about global warming or strategic dependency on OPEC. Since the dawn of the atomic age, armies of scientists and researchers and government officials have invested billions of dollars and countless hours of toil and labor to replicate, in a controlled environment, what the sun is constantly doing: converting matter into energy through a fusion reaction. To figure this out would be to solve humanity’s energy needs once and for all. The development of successful fusion power plants would put an end to all the economic, environmental, and foreign policy troubles that plague the current global energy regime. Unlike windmills and solar panels, the potential of fusion energy is virtually limitless. This vision has spurred a movement of would-be discoverers lighting out for the fame and glory that would accompany the breakthrough of controlled fusion. A recent book chronicles this wild, oft-contentious scientific pursuit. Charles Seife, a former Science magazine writer and the author of the heralded 2000 bestseller, Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, has written a lively account of the history of fusion research—“a tragic and comic pursuit that has left scores of scientists battered and disgraced.”

more from Max Schulz at The New Atlantis here.

From The Guardian:

Last night I attended the prize ceremony for the inaugural Wellcome Trust book prize, awarded to “outstanding works of fiction and non-fiction on the theme of health, illness or medicine”. I was attracted by its slightly barmy mixing of literary disciplines. And I was impressed by the calibre of the judges, among whom were Jo Brand (chair, and 10 years a psychiatric nurse) and Raymond Tallis, one of the few people whose writing clarifies, rather than further muddles, my understanding of neuroscience.

Last night I attended the prize ceremony for the inaugural Wellcome Trust book prize, awarded to “outstanding works of fiction and non-fiction on the theme of health, illness or medicine”. I was attracted by its slightly barmy mixing of literary disciplines. And I was impressed by the calibre of the judges, among whom were Jo Brand (chair, and 10 years a psychiatric nurse) and Raymond Tallis, one of the few people whose writing clarifies, rather than further muddles, my understanding of neuroscience.

The shortlist, which can be viewed in full here, comprised two novels and four non-fiction books ranging between autobiography, investigative journalism and biographical essays. The winning book, Keeper, Andrea Gillies' memoir of caring for a relative with Alzheimer's, hasn't received a single review since its publication in May – something this award will, one hopes, remedy.

Speaking with Brand and Tallis before the ceremony, I wondered which books they thought best demonstrated the qualities they were looking for. Interestingly enough, they both chose novels. Brand described Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest as being about “a very specific time in American history, when psychiatry was very unsophisticated and nurses were really no more than prison warders”. Tallis opted for Mann's The Magic Mountain, which “brilliantly fictionalises medicine, the thrill of science, and the mystery of the human body.”

The prize's website plays a similar game, suggesting García Márquez's Love in the Time of Cholera, Oliver Sacks's The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Ian McEwan's Saturday as likely nominees from the past. But the possibility exists, of course, to reach back much further in the literary record than this. Illness, certainly, was present at the birth of western literature: just think of Apollo, angered by Agamemnon's insulting of the priest Chryses, sending a plague to ravage the Greek army in the Iliad. Medicine is present, too, albeit in primitive form: the many wounds Homer describes are anatomically accurate, while Machaon's herbal remedies and palliative care are doctoring of a sort.

More here. (For Dr. Alvan Ikoku who is sure to win this prize in the future.)

From Nature:

The first appointment in a scheme to recruit expatriate scientists to senior positions in the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) — India's largest science agency — seems to have misfired badly. A US scientist of Indian origin has been dismissed just five months after he was offered the position of 'outstanding scientist' and tasked with helping to commercialize technologies developed at CSIR institutes. Shiva Ayyadurai, an entrepreneur inventor and Fulbright Scholar with four degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, was the first scientist to be appointed under the CSIR scheme to recruit about 30 scientists and technologists of Indian origin (STIOs) into researcher leadership roles. “The offer was withdrawn as he did not accept the terms and conditions and demanded unreasonable compensation,” Samir Brahmachari, director general of the CSIR, told Nature.

The first appointment in a scheme to recruit expatriate scientists to senior positions in the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) — India's largest science agency — seems to have misfired badly. A US scientist of Indian origin has been dismissed just five months after he was offered the position of 'outstanding scientist' and tasked with helping to commercialize technologies developed at CSIR institutes. Shiva Ayyadurai, an entrepreneur inventor and Fulbright Scholar with four degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, was the first scientist to be appointed under the CSIR scheme to recruit about 30 scientists and technologists of Indian origin (STIOs) into researcher leadership roles. “The offer was withdrawn as he did not accept the terms and conditions and demanded unreasonable compensation,” Samir Brahmachari, director general of the CSIR, told Nature.

Ayyadurai denies this. In a 30 October letter to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who is also president of the CSIR, he claims that he was sacked for sending senior CSIR scientists a report that was critical of the agency's leadership and organization. The report, published on 19 October, was authored by Ayyadurai and colleague Deepak Sardana, who joined the CSIR as a consultant in January. Ayyadurai says that the report — which was not commissioned by the CSIR — was intended to elicit feedback about the institutional barriers to technology commercialization. “Our interaction with CSIR scientists revealed that they work in a medieval, feudal environment,” says Ayyadurai. “Our report said the system required a major overhaul because innovation cannot take place in this environment.”

More here.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

We now have everything in place to convert two texts into a game of chess: we simply feed the program the two novels, asking it to play one text as “white” and the other as “black”; the program searches through the white text until it finds the first tuple corresponding to a movable piece (in the case of an opening move, either a pawn or a knight), and then, having settled on the piece that will open, continues searching through the text until it encounters a tuple designating a square to which that piece can be moved. When it has done so, the computer executes that move for white, and then goes to the other text to find, in the same way, an opening move for black. And so it goes: white, black, white, black, until—quite by accident, of course, since we must suppose that the novels know nothing of chess strategy (and our program cannot help them, since it knows only the rules of the game)—one king is mated. Such a set up would be close (there turn out to be interesting differences, but put that aside for now) to permitting two monkeys to play chess against each other by giving each a keyboard and permitting them to jump about on them: send the resulting string of letters to our program, and it scans this string of gobbledygook for tuples that constitute legitimate moves, makes them, and voilà, monkey chess.

more from D. Graham Burnett and W. J. Walter at Cabinet here.