This article by Pervez Hoodbhoy was published simultaneously today in Pakistan (Dawn) and India (The Hindu):

So, how can India protect itself from invaders across its western border and grave injury? Just as importantly, how can we in Pakistan assure that the fight against fanatics is not lost?

So, how can India protect itself from invaders across its western border and grave injury? Just as importantly, how can we in Pakistan assure that the fight against fanatics is not lost?

Let me make an apparently outrageous proposition: in the coming years, India’s best protection is likely to come from its traditional enemy, the Pakistan Army. Therefore, India ought to now help, not fight, against it.

This may sound preposterous. After all, the two countries have fought three and a half wars over six decades. During periods of excessive tension, they have growled at each other while meaningfully pointing towards their respective nuclear arsenals. And yet, the imperative of mutual survival makes a common defence inevitable. Given the rapidly rising threat within Pakistan, the day for joint actions may not be very far away.

Today Pakistan is bearing the brunt. Its people, government and armed forces are under unrelenting attack. South Waziristan, a war of necessity rather than of choice, will certainly not be the last one. A victory here will not end terrorism, although a stalemate will embolden jihadists in south Punjab, including Lashkar-i-Taiba and Jaish-i-Mohammad. The cancer of religious militancy has spread across Pakistan, and it will take decades to defeat.

More here.

Friday, November 27, 2009

Jerry A. Jacobs in The Chronicle of Higher Ed:

Jerry A. Jacobs in The Chronicle of Higher Ed:

The present arrangement of discipline-based departments, combined with interdisciplinary research centers, provides an inelegant but practical way to nurture disciplinary skills while allowing the flexibility for scholars to come together around new and topical areas. Occasionally the results are so compelling that a new discipline is formed. Successful interdisciplinary endeavors are thus transitional. Once they settle into maturity, they increasingly resemble the disciplines they sought to overthrow, at least in their organizational form. Promising new areas of inquiry should be nurtured whether or not they happen to cut across disciplinary lines. They should be encouraged because of their intellectual and practical promise—not because they are interdisciplinary.

Exciting interdisciplinary opportunities undoubtedly exist in some fields, and individual scholars will continue to borrow insights, concepts, and techniques from a diverse portfolio of sources. There is no reason to prohibit creative interdisciplinary projects. Wise deans, provosts, and presidents may be able to attract distinguished scholars precisely because those individuals work on specialties that span adjacent fields or even colleges. The intellectual boundaries of today's research may not map neatly onto disciplinary frameworks developed long ago.

Yet interdisciplinarity is not a panacea. Some interdisciplinary experiments will be stillborn; some interdisciplinary units will prove unwieldy and fracture of their own accord. Remember a cautionary tale from the past: Harvard's department of social relations proved unable to unify anthropology, psychology, and sociology and finally agreed to a divorce in 1972 after more than 20 years of marriage.

The UNESCO Courier has an collection of pieces that Lévi-Strauss wrote for UNESCO (via Savage Minds). From the editorial:

The UNESCO Courier has an collection of pieces that Lévi-Strauss wrote for UNESCO (via Savage Minds). From the editorial:

“The efforts of science should not only enable mankind to surpass itself; they must also help those who lag behind to catch up”,” Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote in his first UNESCO Courier article published in 1951. He contributed to the magazine regularly during the 1950s suggesting ideas he later developed in the works which made him world-famous.

Recommending the unification of methodological thinking between the exact sciences and the human sciences, he underlined in another article that “the speculations of the earliest geometers and arithmeticians were concerned with man far more than with the physical world”. Pythagoras, for one, was “deeply interested in the anthropological significance of numbers and figures”, as were the sages of China, India, pre-Colonial Africa and pre-Colombian America, “preoccupied” with the meaning and specific attributes of numbers.

His idea grew into a thesis on the “mathematics of man – to be discovered along lines that neither mathematicians nor sociologists have as yet been able to determine exactly,” and destined to be “very different from the mathematics which the social sciences once sought to use in order to express their observations in precise terms,” as the father of structural anthropology explained in a 1954 article published in the Social Science Bulletin, another source for this issue.

“Our sciences first became isolated in order to become deeper, but at a certain depth, they succeed in joining each other. Thus, little by little, in an objective area, the old philosophical hypothesis…of the universal existence of a human nature is borne out”, he said in a 1956 document preserved in the UNESCO archives, which opened their doors wide so that this special issue could be, if not definitive, as varied as possible.

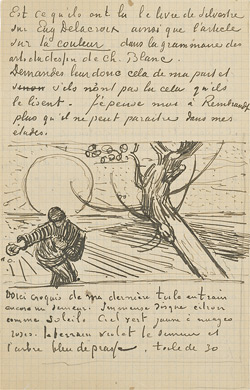

When I did my last post, I hadn't realized that Morgan Meis had already written about Van Gogh's letters at The Smart Set:

A letter makes the world small again, shows a person enmeshed in the day-to-day affairs that everyone understands. Thus, by way of their potentially shocking intimacy or through their potentially overwhelming banality, letters tend to lack the specific elements that are to be found in the actual work of a great artist. Letters, inevitably, are the flotsam and jetsam through which the scholars pick. They contain little meat for you and me.

A letter makes the world small again, shows a person enmeshed in the day-to-day affairs that everyone understands. Thus, by way of their potentially shocking intimacy or through their potentially overwhelming banality, letters tend to lack the specific elements that are to be found in the actual work of a great artist. Letters, inevitably, are the flotsam and jetsam through which the scholars pick. They contain little meat for you and me.

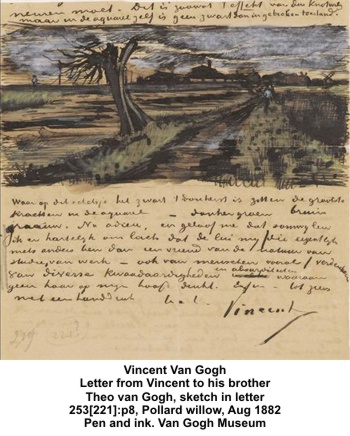

But this is not always the case. Thanks to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the letters of Van Gogh can now be perused in total. There is an exhibit running through January 2010 but, more important for those not able to make the trip, a complete online edition of the letters available at vangoghletters.org. The website is simply amazing. The letters themselves are interesting enough on the personal level. Vincent's last letter to his brother Theo contains the poignant thought, “I’d perhaps like to write to you about many things, but first the desire has passed to such a degree, then I sense the pointlessness of it.” All of the letters to Theo, actually, reveal a thoughtful, sensitive, and loving brother.

In this, Vincent van Gogh is one of us. We see him as a human being negotiating his way through a complicated world. But there is something more, some portion of his greatness contained in these letters. This makes them unusual.

More here.

Black Friday Bonus: Here are two pictures of Morgan and me just before our visit to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Photos by Margit Oberrauch. Copyright 2009.

Andrew Motion in The Guardian:

Michelangelo wrote some wonderful sonnets; Constable's correspondence has a fascinating tough-tenderness; most visualisers have, with varying degrees of success, tried to match words to their images. But Van Gogh's letters are the best written by any artist. Engrossing, moving, energetic and compelling, they dramatise individual genius while illuminating the creative process in general. No wonder readers have long since taken them to heart. No wonder, either, that singers have used them in their songs (“Starry Night”), and film-makers as the basis of their movies (Lust for Life). Their mixture of humble detail and heroic aspiration is quite simply life-affirming.

Michelangelo wrote some wonderful sonnets; Constable's correspondence has a fascinating tough-tenderness; most visualisers have, with varying degrees of success, tried to match words to their images. But Van Gogh's letters are the best written by any artist. Engrossing, moving, energetic and compelling, they dramatise individual genius while illuminating the creative process in general. No wonder readers have long since taken them to heart. No wonder, either, that singers have used them in their songs (“Starry Night”), and film-makers as the basis of their movies (Lust for Life). Their mixture of humble detail and heroic aspiration is quite simply life-affirming.

Received wisdom has it that the letters show Van Gogh as a tortured genius. Yet anyone who has actually read them (rather than watched the movie) will feel uncomfortable about this. There are, of course, harrowing stretches in which he frets about insanity, about poverty and about how others perceive him. But the great majority of them are impressive – even lovable – because, no matter how distressing their surrounding circumstances, they show an extraordinarily calm-sounding good sense and a beautiful directness in their account of complicated emotional states. This sense of balance, which frankly amounts to nobility, has been evident in all editions of his letters, ever since the first was published by his sister-in-law, Jo Bonger, in 1914. In this new edition it is even more vividly manifest.

More here. [A couple of weeks ago Morgan Meis and I saw some of the letters in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, and some of the drawings in them are truly stunning. We agreed they were the best thing in the museum.]

From The New York Times:

One was a middle-aged man who refused to get into the shower. The other was a teenager who was afraid to get out. The man, Leonard, a writer living outside Chicago, found himself completely unable to wash himself or brush his teeth. The teenager, Ross, growing up in a suburb of New York, had become so terrified of germs that he would regularly shower for seven hours. Each received a diagnosis of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, or O.C.D., and for years neither felt comfortable enough to leave the house. But leave they eventually did, traveling in desperation to a hospital in Rhode Island for an experimental brain operation in which four raisin-sized holes were burned deep in their brains. Today, two years after surgery, Ross is 21 and in college. “It saved my life,” he said. “I really believe that.” The same cannot be said for Leonard, 67, who had surgery in 1995. “There was no change at all,” he said. “I still don’t leave the house.” Both men asked that their last names not be used to protect their privacy.

One was a middle-aged man who refused to get into the shower. The other was a teenager who was afraid to get out. The man, Leonard, a writer living outside Chicago, found himself completely unable to wash himself or brush his teeth. The teenager, Ross, growing up in a suburb of New York, had become so terrified of germs that he would regularly shower for seven hours. Each received a diagnosis of severe obsessive-compulsive disorder, or O.C.D., and for years neither felt comfortable enough to leave the house. But leave they eventually did, traveling in desperation to a hospital in Rhode Island for an experimental brain operation in which four raisin-sized holes were burned deep in their brains. Today, two years after surgery, Ross is 21 and in college. “It saved my life,” he said. “I really believe that.” The same cannot be said for Leonard, 67, who had surgery in 1995. “There was no change at all,” he said. “I still don’t leave the house.” Both men asked that their last names not be used to protect their privacy.

More here.

From Science:

After their biggest meal of the year, Americans might reflect on the fate of those moldering Thanksgiving leftovers. Nearly 40% of the food supply in the United States goes to waste, according to a new study, and the problem has been getting worse. “The numbers are pretty shocking,” says Kevin Hall, a quantitative physiologist at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) in Bethesda, Maryland. Food waste is usually estimated through consumer interviews or garbage inspections. The former method is inaccurate, and the latter isn't geographically comprehensive. Hall and his colleagues tried another approach: modeling human metabolism. They analyzed average body weight in the United States from 1974 to 2003 and figured out how much food people were eating during this period. Hall and Chow assumed that levels of physical activity haven't changed; some researchers think that activity has decreased, but Hall and Chow say their assumption is conservative. Then they compared that amount with estimates of the food available for U.S. consumers, as reported by the U.S. government to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

After their biggest meal of the year, Americans might reflect on the fate of those moldering Thanksgiving leftovers. Nearly 40% of the food supply in the United States goes to waste, according to a new study, and the problem has been getting worse. “The numbers are pretty shocking,” says Kevin Hall, a quantitative physiologist at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) in Bethesda, Maryland. Food waste is usually estimated through consumer interviews or garbage inspections. The former method is inaccurate, and the latter isn't geographically comprehensive. Hall and his colleagues tried another approach: modeling human metabolism. They analyzed average body weight in the United States from 1974 to 2003 and figured out how much food people were eating during this period. Hall and Chow assumed that levels of physical activity haven't changed; some researchers think that activity has decreased, but Hall and Chow say their assumption is conservative. Then they compared that amount with estimates of the food available for U.S. consumers, as reported by the U.S. government to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

The difference between calories available and calories consumed, they say, is food wasted. “We called it the missing mass of American food,” says co-author Carson Chow, a mathematician at NIDDK. In 2003, some 3750 calories were available daily per capita; 2300 were consumed, so 1450 were wasted, comprising 39% of the available food supply, the team reports in the November issue of PLoS ONE. This figure exceeds the 27% estimated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) from interviews with consumers and producers.

More here.

Hussein Agha and Robert Malley in the New York Review of Books:

What is the matter with the two-state solution? To this day, it remains the only outcome that appears attuned to reality; the only one that enjoys broad support. Its rough outlines no longer constitute much of a mystery. Yet all this does not so much answer the question as it reframes it: What basic ingredients have been missing from the conventional two-state concept? Why, so widely embraced in the abstract, has it been so stubbornly rejected in practice?

What is the matter with the two-state solution? To this day, it remains the only outcome that appears attuned to reality; the only one that enjoys broad support. Its rough outlines no longer constitute much of a mystery. Yet all this does not so much answer the question as it reframes it: What basic ingredients have been missing from the conventional two-state concept? Why, so widely embraced in the abstract, has it been so stubbornly rejected in practice?

The problem with the two-state idea as it has been construed is that it does not truly address what it purports to resolve. It promises to close a conflict that began in 1948, perhaps earlier, yet virtually everything it worries about sprang from the 1967 war. Ending Israel's occupation of Palestinian territories is essential and the conflict will persist until this is addressed. But its roots are far deeper: for Israelis, Palestinian denial of the Jewish state's legitimacy; for Palestinians, Israel's responsibility for their large-scale dispossession and dispersal that came with the state's birth.

If the objective is to end the conflict and settle all claims, these matters will need to be dealt with. They reach back to the two peoples' most visceral and deep-seated emotions, their longings and anger. For years, the focus has been on fine-tuning percentages of territorial withdrawals, ratios of territorial swaps, and definitions of Jerusalem's borders. The devil, it turns out, is not in the details. It is in the broader picture.

More here.

Seeing the Light

After she draws the pension on Friday

I drive my mother to the graveyard,

She walks among the dead and prays

While I read the newspaper in the car.

I envy how near she is to them, how

Soon she will join the dear departed.

I was in love like that once, consumed

By the idea of ‘love’ until I realised that

It’s not all that people make it out to be.

I envy your faith Mama, your prayer book

Bulging with photographs of the missing,

Your trust in that ghostly other-world

More real to you than the one

You see every day with your eyes.

by Eugene O'Connell

from Diviner; Three Spires Press, Cork, 2009

Pankaj Mishra in The National:

India is one of the world’s oldest civilisations; but as a nation-state it is relatively very new, and its nationalism can still appear weak and unresolved, as became freshly clear in August, when the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party expelled its veteran leader Jaswant Singh. Singh had dared to praise, in a new book about the partition of India, the founder of Pakistan, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Indian nationalists, of both the hardline Hindu and soft-secular kind, see Jinnah as the Muslim fanatic primarily responsible for the vivisection of their “Mother India” in 1947. But Singh chose to blame the partition on allegedly power-hungry Hindu freedom fighters, rather than Jinnah, who he claimed had stood for a united India.

India is one of the world’s oldest civilisations; but as a nation-state it is relatively very new, and its nationalism can still appear weak and unresolved, as became freshly clear in August, when the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party expelled its veteran leader Jaswant Singh. Singh had dared to praise, in a new book about the partition of India, the founder of Pakistan, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Indian nationalists, of both the hardline Hindu and soft-secular kind, see Jinnah as the Muslim fanatic primarily responsible for the vivisection of their “Mother India” in 1947. But Singh chose to blame the partition on allegedly power-hungry Hindu freedom fighters, rather than Jinnah, who he claimed had stood for a united India.

Explaining his motivations, Singh referred back to his origins in Sindh (the province famous for its syncretistic and tolerant Hindu-Muslim culture) and suggested that he could only mourn the subsequent division of pluralist communities on the basis of abstract and singular religious identities. “In Jaisalmer,” he said, “Muslims don’t eat beef, Rajputs don’t eat pork.” Singh went on to speak wistfully of a famous shrine in Indian Sindh that is revered by both Muslims and Hindus.

Singh is not being a romantic. Hindus and Muslims commonly worship at each other’s sites across the subcontinent. One of my most intense childhood memories is of being immersed, by my Hindu Brahmin parents, into the great crowd at the dargah (shrine) of the Sufi saint Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer. I felt a similar sense of wonder earlier this year at another dargah in Pakistan, standing amid ecstatic dancers at a spring festival in Lahore that celebrates the friendship, apparently homoerotic, of a Muslim and a Brahmin boy in the 16th century.

More here.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Robert Darnton in the NYRB:

November 9 is one of those strange dates haunted by history. On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, signaling the collapse of the Soviet empire. The Nazis organized Kristallnacht on November 9, 1938, beginning their all-out campaign against Jews. On November 9, 1923, Hitler's Beer Hall Putsch was crushed in Munich, and on November 9, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and Germany was declared a republic. The date especially hovers over the history of Germany, but it marks great events in other countries as well: the Meiji Restoration in Japan, November 9, 1867; Bonaparte's coup effectively ending the French Revolution, November 9, 1799; and the first sighting of land by the Pilgrims on the Mayflower, November 9, 1620.

On November 9, 2009, in the district court for the Southern District of New York, the Authors Guild and the Association of American Publishers were scheduled to file a settlement to resolve their suit against Google for alleged breach of copyright in its program to digitize millions of books from research libraries and to make them available, for a fee, online. Not comparable to the fall of the Berlin Wall, you might say. True, but for several months, all eyes in the world of books—authors, publishers, librarians, and a great many readers—were trained on the court and its judge, Denny Chin, because this seemingly small-scale squabble over copyright looked likely to determine the digital future for all of us.

Google has by now digitized some ten million books. On what terms will it make those texts available to readers? That is the question before Judge Chin. If he construes the case narrowly, according to precedents in class-action suits, he could conclude that none of the parties had been slighted. That decision would remove all obstacles to Google's attempt to transform its digitizing of texts into the largest library and book-selling business the world has ever known. If Judge Chin were to take a broad view of the case, the settlement could be modified in ways that would protect the public against potential abuses of Google's monopolistic power.

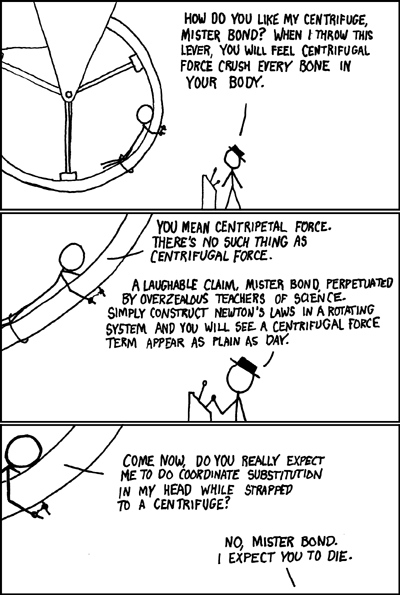

Via Paul Krugman, at xkcd:

To celebrate Francis Bacon’s centenary in 2009, Tate Britain mounted a retrospective exhibition that was subsequently shown at the Prado in Madrid and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Bacon’s theater of cruelty was an enormous popular success at all of its venues, but especially in New York, where he was hailed by fans as the greatest painter of the twentieth century. However, such clouds of hyperbole were already a touch toxic following the sale in 2008 of a flashy triptych for $86 million, and serious reviews of the Met show were anything but favorable. Also, those of us who care about the integrity of an artist’s work were worried by the appearance on the market of paintings that, if indeed they are entirely by him, Bacon would never have allowed out of the studio. As a longtime fan of Bacon, I have strong feelings about these matters. My admiration dates back to World War II, when, like many another art student, I was captivated by an illustration of a 1933 painting entitled Crucifixion in a popular book called Art Now, by Britain’s token modernist, Herbert Read (first published in 1933, and frequently reprinted). Read’s text was dim and theoretical, but his ragbag of black-and-white illustrations—by the giants of modernism, as well as the chauvinistic author’s pets—was the only corpus of plates then available. This Crucifixion—a cruciform gush of sperm against a night sky, prescient of searchlights in the blitz—was irresistibly eye-catching. But who Bacon was, nobody seemed to know.

more from John Richardson at the NYRB here.

JULIAN BARNES The main literary event of 2009 was the death of John Updike. Generous to the last, he left us two posthumous books: in prose, My Father’s Tears, and in verse, Endpoint (both Hamish Hamilton), an account of his last years – and days – of grateful, tender looking around. He was still writing in his final weeks (“Days later, the results came casually through: / the gland, biopsied, showed metastasis”) and correcting proofs on his deathbed. Over here, death afforded him no courtesy, and the stories received several reviews of impudent stupidity; the longer view will see them as a fit end to the staggeringly rich arc of story collections which began fifty years ago with “The Same Door” (1959). In part-homage, Everyman usefully reprinted the full version of “The Maples Stories”, one of his keenest anatomies of the marriage problem. Everyman also publish Updike’s final reworking of the Rabbit quartet, retitled by him as Rabbit Angstrom. Rereading confirms it as the greatest American novel of the second half of the twentieth century. An Angstrom is a hundred-millionth of a centimetre: a fitting name, since Updike, apart from his many other virtues, simply saw in finer detail than most of his contemporaries.

more from various literary bigwigs at the TLS here.

September Song

Autumn has come stripping the trees

to make them look like an army in defeat.

Soon everything will appear bereft,

even the girls on the street in décolletage

and canal swans nesting by the side of the bridge:

A pair of them in a swan-marriage,

schooled to be faithful companions.

Roads are brimming with slow-motion traffic

going out of the city, home to the foothills,

to time in the garden pulling weeds,

the Hollywood epic on late-night TV:

the one with the long list of etceteras

scrolled in haste before we turn over

in the double bed of brass reflections.

by Gerard Smyth

from The Mirror Tent

publisher: Dedalus, Dublin, 2007

From LA Times:

Right-wing pro-marriage advocates are correct: Monogamy is definitely under siege. But not from uncloseted polyamorists, adolescent “hook-up” advocates, radical feminists, Godless communists or some vast homosexual conspiracy. The culprit is our own biology. Researchers in animal behavior have long known that monogamy is uncommon in the natural world, but only with the advent of DNA “fingerprinting” have we come to appreciate how truly rare it is. Genetic testing has recently shown that even among many bird species — long touted as the epitome of monogamous fidelity — it is not uncommon for 6% to 60% of the young to be fathered by someone other than the mother's social partner. As a result, we now know scientifically what most people have long known privately: that social monogamy does not necessarily imply sexual monogamy.

Right-wing pro-marriage advocates are correct: Monogamy is definitely under siege. But not from uncloseted polyamorists, adolescent “hook-up” advocates, radical feminists, Godless communists or some vast homosexual conspiracy. The culprit is our own biology. Researchers in animal behavior have long known that monogamy is uncommon in the natural world, but only with the advent of DNA “fingerprinting” have we come to appreciate how truly rare it is. Genetic testing has recently shown that even among many bird species — long touted as the epitome of monogamous fidelity — it is not uncommon for 6% to 60% of the young to be fathered by someone other than the mother's social partner. As a result, we now know scientifically what most people have long known privately: that social monogamy does not necessarily imply sexual monogamy.

In the movie “Heartburn,” the lead character complains about her husband's philandering and gets this response: “You want monogamy? Marry a swan!” But now, scientists have found that even swans aren't monogamous.

More here.

From Scientific American:

Sam paged me at 9 p.m., crying. It had started with his hair, which he was convinced was falling out. And although his work as a teacher’s aide had “filled him with love and joy,” he was sure his boss had given him a nasty look at the lunch break, and he felt utterly sick inside. Later Sam had phoned his partner, who had seemed distant. Afraid he was about to be dumped, Sam locked himself in the staff bathroom and cried for almost an hour, failing to finish his work and preventing others from using the facilities. Sam is a drama queen—a person who reacts to everyday events with excessive emoton and behaves in theatrical, attention-grabbing ways. This type is the friend who derails a casual lunch to tell you a two-hour story about the devastating fight she had with her partner or the co-worker who constantly obsesses about how he is about to lose his job and needs your support to make it through the day. The drama queen worships you one minute and despises you the next, based on overreactions to minor events.

Sam paged me at 9 p.m., crying. It had started with his hair, which he was convinced was falling out. And although his work as a teacher’s aide had “filled him with love and joy,” he was sure his boss had given him a nasty look at the lunch break, and he felt utterly sick inside. Later Sam had phoned his partner, who had seemed distant. Afraid he was about to be dumped, Sam locked himself in the staff bathroom and cried for almost an hour, failing to finish his work and preventing others from using the facilities. Sam is a drama queen—a person who reacts to everyday events with excessive emoton and behaves in theatrical, attention-grabbing ways. This type is the friend who derails a casual lunch to tell you a two-hour story about the devastating fight she had with her partner or the co-worker who constantly obsesses about how he is about to lose his job and needs your support to make it through the day. The drama queen worships you one minute and despises you the next, based on overreactions to minor events.

More here.

So, how can India protect itself from invaders across its western border and grave injury? Just as importantly, how can we in Pakistan assure that the fight against fanatics is not lost?