by Ahmad Saidullah

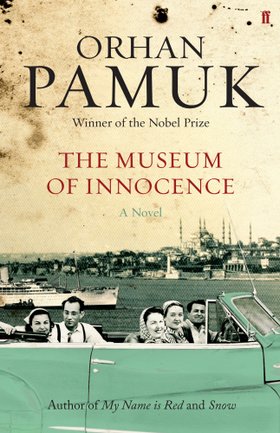

The Museum of Innocence, Orhan Pamuk’s first novel since he won the 2006 Nobel Prize, is set in the period following the mid-seventies when the author was buying books in Istanbul “like a frantic person who was desperate to understand why Turkey was so poor.” A student of Turkish history and the politics of civilization, Pamuk noted in an essay on his library in The New York Review of Books that “in the 1970s, the stars of every bookstore were the large historical tomes that sought out the root causes of Turkey’s poverty and ‘backwardness’ and its social and political upheavals.”

The Museum of Innocence, Orhan Pamuk’s first novel since he won the 2006 Nobel Prize, is set in the period following the mid-seventies when the author was buying books in Istanbul “like a frantic person who was desperate to understand why Turkey was so poor.” A student of Turkish history and the politics of civilization, Pamuk noted in an essay on his library in The New York Review of Books that “in the 1970s, the stars of every bookstore were the large historical tomes that sought out the root causes of Turkey’s poverty and ‘backwardness’ and its social and political upheavals.”

The Museum of Innocence frames this history around the star-crossed fates of characters from the Turkish elite who live in Nişantaşı, a wealthy neighborhood in the Pera part of Istanbul where Pamuk grew up, and their poorer counterparts in the city. The central plot of Museum, a six-page story about desire and difference, appeared in The New Yorker. While shopping for Sibel, his rich socialite fiancée, Kemal Basacı, the son of one of Istanbul’s wealthiest industrialists, falls for Füsun Keskin, the shopgirl at the boutique, who sells him a fake designer handbag.

Füsun, whose name means “charm,” “enchantment,” “magic,” and “spell” in Turkish, happens to be Kemal’s poor cousin. The Basacıs shun her family members not just for their poverty but for their scandalous and somewhat déclassé decision in allowing Füsun to compete in a beauty pageant. Using the return of the knock-off “Jenny Colon” handbag (the real Jenny Colon was a nineteenth-century actress and Nerval’s muse) as a pretext for meeting again, Kemal and Füsun, a sexually precocious beauty modelled on Lolita, start a clandestine affair in an apartment in Merhamet. Kemal neglects the family business as his passion grows. Frustrated with his obsession and worried about the public odium that will follow the scandal, Sibel breaks off the engagement. Füsun disappears and Kemal on his visits to the Keskins starts collecting tokens of the affair that become his Museum of Innocence.

In the drawn-out second part of the book, Kemal resumes contact with Füsun when she returns to Istanbul with a husband, Feridun, an aspiring screenwriter. Kemal and Feridun pretend to help Füsun become a Yeşilçam film star but secretly do all they can to thwart her. Eventually, Kemal founds Lemon Films and produces a film adaptation of Turkish novelist Halit Ziya Uşaklıgil’s Broken Love (Kırık Hayatlar), a once-censored novel about unrequited love, in which Füsun stars. Her film career is shortlived.

The book ends with chapters on collectors and museums but not before Orhan Pamuk makes his second deus ex machina appearance in the book. He addresses Kemal in a ponderous metafictional apostrophe: “in the book you are telling me your own story and saying ‘I,’ Kemal Bey. I am speaking in your voice. Right now I am trying very hard to put myself in your place, to be you.”

Although Museum is written in an accessible middle style with balanced sentences that are almost flat and static, with few of the syntactical hijinks of some of Pamuk’s other novels, it is one of his more troubling books. He has claimed that this novel is about love and “love,” says a character in the book, “is Leyla and Macnun,” a reference to the Azeri poet Fużūlī’s classic ghazal about ill-starred lovers. Much of Museum’s plotline, though, moves between banal dialogue (“I am a penniless shopgirl, while you are the son of a wealthy factory owner”), platitudes (“Happiness means being close to the one you love, that’s all”) and coy, almost adolescent, descriptions of sex suited to the Yeşilçam romantic film melodramas that Pamuk adored in 1970s and ’80s Istanbul. Ever the bibliophile, Pamuk does not fail to include references to Nabokov’s Lolita, Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Nerval’s Aurélia and Uşaklıgil who had modelled his style on French romanticism. He also refers to Flaubert’s affair with Louise Colet and the use of love tokens in Madame Bovary.

Read more »