Train station in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, in May of 2019.

Train station in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, in May of 2019.

by Niall Chithelen

I tried to accelerate out of winter, really speed through things, but I think I messed up and broke spring. Definitely something amiss—nothing grew in; instead a green city flashed into a grey one. Lawns were unfurled overnight, flowers appeared, and now I sneeze many times in a row each morning. This, I think, must be a sign.

I spent the winter going from indoors to indoors. I put my coat on the back of the chair before sitting down. I took 90-minute subway rides and 12-hour train rides. I overstayed my welcome on every phone call. I made mistakes.

Some might tell you that our haphazard “spring” originates with much larger forces, that its sudden appearance is in fact the party-state at work, its conflation with summer the result of climate change, its wonders and tatters all borne of humanity. They might mention beautification and propaganda. They might use the word “anthropocene.”

But I don’t know. I suspect it was probably some moment, something I did. Next year, everything might go back to normal, and next spring’s problems might once again be caused by humanity. I will make amends, do better, and maybe we can all go back to how it ought to be—locking eyes after a fifth sneeze, pausing, and then laughing together through our uncertain spring.

by Nickolas Calabrese

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

Stepping back for a moment, it should be obvious that people of all stripes use music as a tool. Not just those who play instruments or sing or generally make music, but anyone who listens to music. It has an instrumental value in human culture. For instance, when the organ roars over the congregation the parishioners prepare to chant hymns to God. Or when you’re about to do a hard workout and you blast 50 Cent to get in the zone. Perhaps you want to set the mood for making love—easy, Marvin Gaye. When studying, many turn to classical because of it’s melodic flowering as ambient background noise. It is uncontroversial to say that many of us at some point or another use music as an instrument to hype us on what we are actually trying to achieve in that moment. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

As the job-displacing effects of markets and global integration and the cultural shocks of large immigration have rattled workers, particularly the less skilled ones, their reactive turn to populism in different parts of the world has dismayed liberals. This has been reinforced by resentment against centralized bureaucracies (not just in Brussels or Washington but also in Mexico City or Delhi or Jakarta) run by professionals and technical experts whose dispensations often ignore local realities and sensibilities. The alliance between liberals and workers that used to form the backbone of centrist democratic parties is getting frayed, as in the minds of many blue-collar workers the liberals with their mobile professional skills come across as privileged meritocrats and rootless cosmopolitans (‘citizens of nowhere’).

Global markets and mobility of capital have required standardization and harmonization of local rules and regulations, which some communities feel are ironing out their local distinctiveness and proximity-based personalized networks. Increasing market concentration in large corporate firms, their blocking of small business, capturing of state power in democracies through strong lobbies and copious election funding, and weakening of labor organizations and depressing labor share have made many small people precarious in their livelihood and suspicious of markets.

State-provided public services which are supposed to relieve the harshness of the market are everywhere riddled with bureaucratic indifference, malfeasance, and resistance to reform, while the better-off liberals are increasingly seceding from them. In developing countries the public delivery of social services is often so dismal (with inept, corrupt or truant official providers) that in contrast the image of voluntary community organizations (including charitable religious institutions run by Muslim, Hindu or Christian evangelicals) trying to fill in the gap is often much better than that of the state. Even when the state delivery mechanisms work reasonably well, the projects often do not involve the people but simply treat them as passive objects of the development process. (In rich countries communities have sometimes rejected negotiations over their heads by corporate and city officials to help investment in the community—as in the recent case of the failed Amazon investment proposal for Queens in New York). Read more »

.

—Thoughts of 77 summer solstices,

hopefully anticipating 78

.

situated between a pair of equinoxes

a blazing solstice— an apex of angles

and ellipses; parabolas scribed by

inertia and mass in a count of months

governed by curves of gravity

at a point when all things reverse

I sweat beneath a star so close

the joist slung across my shoulder

as I stride over dry earth to a nascent house

is as warm to my touch by its radiation

as the thought of you beneath my hand

Jim Culleny

4/27/19

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

On a whim I decided to visit the gently sloping hill where the universe announced itself in 1964, not with a bang but with ambient, annoying noise. It’s the static you saw when you turned on your TV, or at least used to back when analog TVs were a thing. But today there was no noise except for the occasional chirping of birds, the lone car driving off in the distance and a gentle breeze flowing through the trees. A recent trace of rain had brought verdant green colors to the grass. A deer darted into the undergrowth in the distance.

The town of Holmdel, New Jersey is about thirty miles east of Princeton. In 1964, the venerable Bell Telephone Laboratories had an installation there, on top of this gently sloping hill called Crawford Hill. It was a horn antenna, about as big as a small house, designed to bounce off signals from a communications satellite called Echo which the lab had built a few years ago. Tending to the care and feeding of this piece of electronics and machinery were Arno Penzias – a working-class refuge from Nazism who had grown up in the Garment District of New York – and Robert Wilson; one was a big picture thinker who enjoyed grand puzzles and the other an electronics whiz who could get into the weeds of circuits, mirrors and cables. The duo had been hired to work on ultra-sensitive microwave receivers for radio astronomy.

In a now famous comedy of errors, instead of simply contributing to incremental advances in radio astronomy, Penzias and Wilson ended up observing ripples from the universe’s birth – the cosmic microwave background radiation – by accident. It was a comedy of errors because others had either theorized that such a signal would exist without having the experimental know-how or, like Penzias and Wilson, were unknowingly building equipment to detect it without knowing the theoretical background. Penzias and Wilson puzzled over the ambient noise they were observing in the antenna that seemed to come from all directions, and it was only after clearing away every possible earthly source of noise including pigeon droppings, and after a conversation with a fellow Bell Labs scientist who in turn had had a chance conversation with a Princeton theoretical physicist named Robert Dicke, that Penzias and Wilson realized that they might have hit on something bigger. Dicke himself had already theorized the existence of such whispers from the past and had started building his own antenna with his student Jim Peebles; after Penzias and Wilson contacted him, he realized he and Peebles had been scooped by a few weeks or months. In 1978 Penzias and Wilson won the Nobel Prize; Dicke was among a string of theorists and experimentalists who got left out. As it turned out, Penzias and Wilson’s Nobel Prize marked the high point of what was one of the greatest, quintessentially American research institutions in history. Read more »

by Thomas O’Dwyer

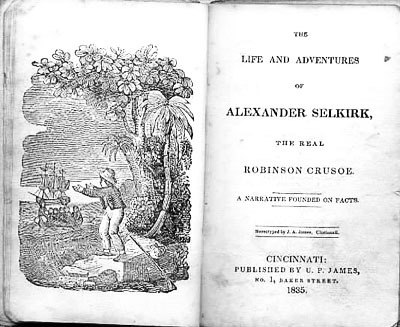

The enigma of the castaway existed long before Robinson Crusoe was published 300 years ago in April 1719, but nothing had ever enthralled the growing reading public of his time like Daniel Defoe’s now classic novel. And, thanks to Defoe, the curse of the desert-island cartoon remains with us – a circular sandbank, a palm tree, a ragged castaway. All that’s required is for a New Yorker magazine funnyman to append an enigmatic or incomprehensible caption. The castaways too – sometimes called Robinsonades but don’t encourage it – are still with us. Tom Hanks communes with a volleyball in a film named, yes, Cast Away, and Matt Damon goes one-up on him in The Martian by claiming to be “the first person to be alone on an entire planet.” New movie variants on the theme have been released almost every year since the 1954 Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Luis Buñuel’s first colour film.

So who reads the original Robinson Crusoe today? This book has been called the first English novel, or imperialist propaganda, or a textbook of capitalism. Since the nineteenth century, it has been a children’s book – more specifically, a boys’ adventure book, sitting on the same shelf as Treasure Island. A cursory search of Amazon’s statistics yields a surprise. Among many editions still on sale, the novel ranks number 358 in the Classic Action & Adventure genre, number 615 in Children’s Classics, and number 202 in the Kindle store’s Fiction Classics. Those are impressive rankings for an archaic seafaring tale that was first published 103 years after the death of William Shakespeare.

In academia, Robinson Crusoe has long been part of the debate on the origins of the first English novel. Of course, in Western literature, Don Quixote is the outstanding claimant, but Crusoe did set up the English narrative structure that authors have riffed on ever since. When Crusoe’s ink supply runs out on the island, the author noticeably transitions from writing a journal to crafting a novel. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress was published forty years before Crusoe and was probably the last fictional, albeit devotional, work approved of by the various churches. After Crusoe came the deluge – Moll Flanders, Fanny Hill, Tom Jones, Vanity Fair, and hundreds more. To hell with devotion. The novels teem with flawed and moral castaways who must find salvation within themselves, if ever. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019.

Sughra Raza. Enlightened, April, 2019.

Digital photograph.

by Mary Hrovat

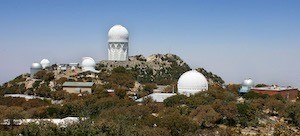

When I returned to school after my first marriage ended, I had to decide what to study. I’d been working toward a degree in history when I dropped out of a community college to get married, but I’d always been drawn to astronomy. One of the reasons I chose astronomy over history, or any other option, was that I felt that astronomy contained many of the other things I was interested in. To put it another way, I thought that if I didn’t study astronomy, I would regret it, but if I did study it, I wouldn’t necessarily lose touch with the other things I was interested in because they were all part of astronomy, in one way or another.

When I returned to school after my first marriage ended, I had to decide what to study. I’d been working toward a degree in history when I dropped out of a community college to get married, but I’d always been drawn to astronomy. One of the reasons I chose astronomy over history, or any other option, was that I felt that astronomy contained many of the other things I was interested in. To put it another way, I thought that if I didn’t study astronomy, I would regret it, but if I did study it, I wouldn’t necessarily lose touch with the other things I was interested in because they were all part of astronomy, in one way or another.

My degree is actually in astrophysics, and obviously it involved a lot of physics and mathematics. To see how the universe works, you have to understand gravitation, nuclear fusion, thermodynamics, atomic physics, and much more. In addition, to use and design telescopes and detectors, you need to know about optics, electronics, and materials science. Although I started out with very little background in math, I wound up with a minor in mathematics. By the time I had taken all the math classes required for the degree, and a fourth semester of calculus (which I hoped would help me understand my physics classes better), I was only three credits away from a math minor, so I took a class in linear algebra.

Astronomy also has obvious links to chemistry and geology. The story of the universe is, from one viewpoint, the story of chemical evolution, the development of more complex chemical elements as stars turned hydrogen and helium into more complex elements through nucleosynthesis. To study planets and moons, we can sometimes apply what we know about the rocks and weather and geological processes of Earth. Geology also comes into play in other ways. For example, one piece of evidence for the dinosaur-killing asteroid that struck Earth around 65 million years ago is a thin layer of iridium in Earth’s crust. Read more »

by Joan Harvey

In the dark times

Will there be singing?

There will be singing.

Of the dark times.

(Bertolt Brecht)

I like the idea of Industrial music as a kind of corrupted psychedelia – the same derangement of the senses, but the childhood innocence has gone. (Comment on YouTube of Throbbing Gristle’s Discipline)

I respond this way again and again, always a split second after each fricative machine growl. Half dreaming now and forced into pure response, I regress. The animal brain writhes sensuously in its own mere selfness. I am at the edge of a pleasure rarely visited. The possibility of ecstasy—being out of myself—is nearly always either novel enough to marvel at (a strictly front-of-brain act) or strange enough to scare me back into my body. (Alexander S. Reed, Assimilate 304) [i]

Most people I know not only don’t care for this music, but probably dislike it intensely.

I can’t really imagine people who don’t already enjoy this sort of music walking into one of these events and actually having a good time.

Therefore proselytizing should probably not be my aim.

We want to share our pleasures and convince others, but sometimes from the beginning it’s a lost cause.

Still, its a part of my existence most people don’t see. And in a way it’s somewhat surprising to me.

Oddly, I began going to industrial shows rather late in life.

They’re more in the line of a thing a teen goth would discover.

When we’re lucky we continually discover new pleasures.

And with luck, many of them. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Jeroen Bouterse

In the school vacation, I finally decided to go on what is probably my only-ever academic pilgrimage: I visited Max Weber’s tombstone in the Bergfriedhof cemetery in Heidelberg.

I had intended to go for some time. In my original plans, I’d go on foot (from the Netherlands) like a proper pilgrim, but after years of failing to go through I had come to realize that was not going to happen anytime soon. So I went by train. Which was too easy; I stood next to the monument before I knew it. I’m still coming to grips with the fact that only on the first time can you do a thing like this properly – that is, with enough ascetic self-denial to mark the purposefulness of your actions – and that I messed up that one chance.

Oh well. Isn’t it fitting to feel the charismatic potential of this particular relic being sapped by the very efficiency of modernity – the stahlhartes Gehäuse of the InterCity Express, working unfailingly to disenchant this tiny part of the world, too. Except for one detail, which I’ll get to later.

I fell in love with Weber as a history undergraduate. We read a fragment of the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The combination of a big and, not unimportantly, Western-centered thesis with detailed, painstaking social and historical explanations seemed a best of two worlds. More than that, Weber’s explanations, rather than reducing the ideas and deepest convictions of the people and movements he studied to some other variable, gave center stage to those convictions. He demonstrated that historical explanation involved understanding the beliefs and values laid down in historical texts, thereby at least partly justifying what I felt most comfortable doing. Read more »

by Joshua Wilbur

As you read these words, someone (or some thing) could be creeping up behind you.

Maybe you’re sitting at your desk. Or at your kitchen table. Or on a half-empty train. Behind you looms an encroaching presence, a silent observer. I picture a middle-aged man in a black suit — a tired and unfeeling assassin— but imagine whatever or whomever you like. A mythical monster, a scorned lover.

Someone might just be there. Right behind you. You won’t know for certain until you look.

* * *

We humans don’t have eyes in the back of our heads. Evolution didn’t budget for that luxury. Some animals—deer, horses, cows—have eyes on the sides of their heads, allowing them a wide field of vision. Other animals—humans, dogs, cats—have their eyes closer together and facing forward, allowing them to better judge depth and distance.

So while grass-grazers enjoy peripheral, panoramic vision their hungry hunters quickly spot them through dense forest. This suggests a simple rule of thumb for distinguishing the skulls of predators from those of prey: “Eyes in the front, the animal hunts. Eyes on the side, the animal hides.”

Eyes in the back, though, would require too many complex mutations, and we do well enough craning our necks to find food. Our bodies have been molded over millions of years to fulfill carnal desires, desperate for what’s in front of us: arms stretching out, noses protruding, mouths gnawing ahead. Biology has determined our fate as forward-oriented creatures and given us a great fear of that which lies outside our perception. Read more »

Photo of moon with a jet vapor trail taken from my balcony in April of 2015.

by Carol A Westbrook

“Medicare for All” is a battle cry for the upcoming national elections, as voters’ health care costs continue to skyrocket. Universal Medicare, they believe, will provide free health care, improve access to the best doctors, and lower the cost of prescription drugs. Is it a dream, or is it a nightmare?

I am 100% in favor of universal health care, but believe me, it ain’t gonna be free. True, I’m not an economist–I’m a doctor–but I can do the math. I’ve had years of experience, both practicing under Medicare’s system and as a Medicare patient, and I understand something about health care costs. Few voters under age 65 understand what Medicare provides, and even fewer have a grasp on what it will cost the government–and ultimately the taxpayer–to extend it to all.

What Medicare provides for free is Medicare A insurance, which covers inpatient hospital, costs. To cover outpatient and emergency room visits, the senior must purchase Part B, which covers 80% of these charges. Medicare B costs $135/month plus a sliding scale based on income. Prescription drug coverage requires purchasing Medicare D from a private company. (Medicare C is alternative private insurance). Medicare A, B and D premiums are all deducted from the monthly Social Security check. Additionally, a senior may purchase a Medicare Supplement from a private insurance company, which covers the un-reimbursed Part A, and B costs. Confusing? Here are two examples. Read more »

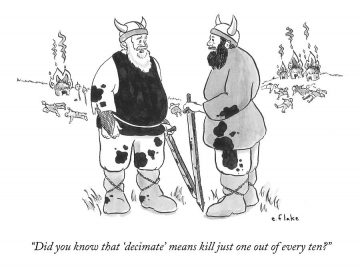

by Gabrielle C. Durham

If you took Latin, then you probably have a larger vocabulary than the average bear, and you are more likely to have strong opinions on some words you vaguely remember based on Latin roots (cognates). For example, folks are more commonly using “decimate” to mean destroy or devastate, and it annoys the living materia feculis out of me. Decimate originally meant to kill every 10th person, based on the Latin word for 10 (decem), which is so oddly and satisfyingly specific. “Devastate” and “destroy” are already well known and used, so why do they need another alliterative ally in little weirdo “decimate”?

If you took Latin, then you probably have a larger vocabulary than the average bear, and you are more likely to have strong opinions on some words you vaguely remember based on Latin roots (cognates). For example, folks are more commonly using “decimate” to mean destroy or devastate, and it annoys the living materia feculis out of me. Decimate originally meant to kill every 10th person, based on the Latin word for 10 (decem), which is so oddly and satisfyingly specific. “Devastate” and “destroy” are already well known and used, so why do they need another alliterative ally in little weirdo “decimate”?

Another little sneak is “cleave.” Meaning #1 is to adhere tightly and closely or unwaveringly. Meaning #2 is to divide or split, to separate, or to penetrate a material by or as if by cutting or tearing. The second meaning is where we get “cloven” as in “cloven hoof,” the tool “cleaver,” “cleft” as in “cleft palate,” and “cleavage.” Both versions arose before the 12th century. The first meaning comes from Old English clifian by way of Middle English clevien. The second meaning comes from Middle English cleven from Old English cleofan and likely Old Norse kljufa, meaning to split. How can these words be so close for almost a millennium with polar opposite meanings? Read more »

by Abigail Akavia

Two weeks ago I celebrated Passover with my family. It was an intimate affair, just four adults and three preschoolers in the small dining room of our rented apartment in Leipzig. Our secular way of life makes Passover, for us, a holiday of light-to-non-existent religious content; nonetheless the richness of the symbolism and of the ritualistic foods is still something we enjoy. Making the Seder palatable to the kids, both the dinner itself and its ritualistic elements, became the central concern for us, their perpetually exhausted parents. The traditional text read in the Seder, the Haggadah, is cryptic in its Aramaic expressions and passages of Talmudic hermeneutics, on which the guests, both young and old, are encouraged to ask questions. But our distaste for the way the myth of Passover resonates in contemporary nationalistic discourse in Israel and elsewhere has brought us to include alternative content in our Seders, stories of other historical struggles towards freedom, which have often been conceived in terms that echo the story of Exodus. This year we read parts of the Hagaddah composed by Rabbis for Human Rights, which was originally read in a detention camp for African refugees in the Israeli desert in 2016, and includes Bob Marley’s Redemption Song. When we lived in Chicago, we told stories of Harriet Tubman and The Underground Railroad.

An Israeli Seder is not dissimilar to American Thanksgiving: a long meal that commemorates the founding of the nation, along with the post-nationalistic reckoning that both holidays can prompt. In both cases, a religious-historical myth becomes incarnated in food. Thus, the matzo, the most important culinary feature of Passover, reminds us of the unleavened bread that the Israelites hastily prepared when they fled their enslaving Egyptians. Every other part of the meal is also meant to symbolize part of the story, that of the Hebrews’ struggle to become a nation. (The series of hardships which the Seder is meant to recall may explain why the Seder meal, while as excessive as a Thanksgiving dinner, is arguably less delicious.) Read more »

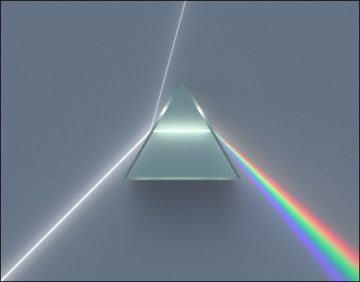

in the matrix of a prism is magic

of two kinds, the inestimable

and that which can be counted

—the inestimable cannot be counted

by definition

if I say red is passionate hot sexy

or if I say red’s the color of death

in unstoppable bleeding

or that its fresh blush reminds me

of one spectacular sunrise

or the touch of you

there’s no calculation I can make

that will sum red’s isness because

as it comes by refraction

from the nothing of white

it may enter a zone

of the most inexplicable

part of mind which is always

putting its private spin on things

but

if I say red’s frequency is 4.3 times

ten to the fourteenth hertz

I’ve dropped into the estimable

spectrum of words which

…….. when so precisely split

leave’s no room for imagination

which just makes me blue

Jim Culleny

4/30/19

by Shawn Crawford

In 1904 America, of boys between the ages of ten to fifteen, 26% worked full time away from home. In the textile mills of New England, children began working at age six for twelve to sixteen hour shifts. When dozing off, cold water would be thrown on them. Ingrates. At the turn of the twentieth century, 70% of children working as migrant pickers in Colorado’s fields had become deformed from the labor.

Given the horrendous conditions, one would think child labor laws sped their way through congress at the beginning of the twentieth century. Instead, a decades-long battle saw legislators bellowing for the rights of business owners and decrying the laziness of the American worker. Chief among these was Weldon Heyburn, an Idaho senator and Theodore Roosevelt’s nemesis. Heyburn thought anyone, including children, that didn’t work from sunup to sundown an idler. And the rights of the business owner had to remain sacred; if someone wanted to hire a fetus to dig coal then by god the government had to protect that right. One can only assume today’s health-care debate would have caused Heyburn’s head to explode.

But after the hysteria and grandstanding and rhetoric died down, sensible child labor laws became established, including the complete banning of children from certain occupations. The pace of industrialization simply outran most people’s understanding of what children could safely do, and as always certain ruthless businesses were happy to exploit the situation. Besides which, the idea of childhood as a distinct time of development separate from adulthood remained a new and contentious idea. For years, children existed as miniature adults, and the faster they took up the work and learned the realities of the adult world the better. Both culture and science would come to understand children as different from adults on all levels: emotionally, physically, and psychologically.

But as we usually do, Americans have forgotten their past and proved incapable of applying former lessons to new contexts. Because while we protect children from labor and most other unpleasant adult responsibilities, we have no problem unleashing them to run free in all the perks of adulthood. Read more »