by R. Passov

The economics of health insurance is of particular importance today. Health insurance has become a major issue of public policy. Some form of national health insurance is very likely to be enacted within the next few years. —Martin Feldstein 1

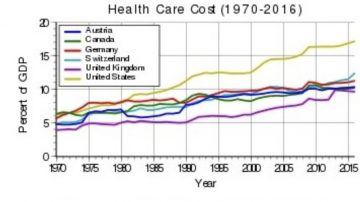

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Turns out, like many economists, he was half right. While a truly national health scheme is still in the making, health care spending is now 18% of GDP, and growing.

Feldstein, known to his friends as Marty, was an interesting guy. For outstanding contributions to economics by an economist under 40, he was awarded the Bates Medal. He was President Reagan’s chief economic advisor, a long-time teacher at his alma matter, Harvard, and managed to retain the presidency and CEO titles at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) from 1977 until his passing in 2019. (He stepped aside from 1982 to 1984 to serve Reagan.)

The NBER describes itself as a private, non-profit research organization and then adds that it has been the source for most leaders of the Council of Economic Advisors. The Council is in fact a government entity, constituting the chief economic advisors to the Office of the President, while the National Bureau, which sounds like it is, is not.

Anyway, fifty years ago, Feldstein took his economics – the ‘markets solve everything’ kind – and reached the following conclusion: The problem with healthcare is Health Insurance. Eliminate insurance wrote Feldstein, and market forces would reign in the runaway price of health services. Read more »

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

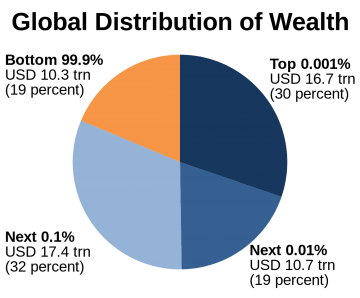

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.”

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.” We are all aware that from amongst the vast diversity of life forms that inhabit the earth, human beings are exceptional. But while human beings are capable of inexhaustible creativity and goodness, they also have the potential to commit the most heinous acts and demeaning of fellow human beings. Accounting for such a phenomenon in the human condition and the committing of abominable acts towards their own species, is an issue that perplexes many. Perhaps the answer to such a question can be found by studying the genes or analysing the brain functioning of the perpetrators, but that could involve investigating entire populations who knowingly condone or participate in such acts. A simpler answer could be that human beings have yet to evolve into a species that is incapable of acts of inhumanity. David Livingstone Smith’s book Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others offers us insight into the processes that lead to the designating of fellow human beings as ‘subhuman’ and makes possible the potential for human beings to perpetrate acts that can only be considered as evil.

We are all aware that from amongst the vast diversity of life forms that inhabit the earth, human beings are exceptional. But while human beings are capable of inexhaustible creativity and goodness, they also have the potential to commit the most heinous acts and demeaning of fellow human beings. Accounting for such a phenomenon in the human condition and the committing of abominable acts towards their own species, is an issue that perplexes many. Perhaps the answer to such a question can be found by studying the genes or analysing the brain functioning of the perpetrators, but that could involve investigating entire populations who knowingly condone or participate in such acts. A simpler answer could be that human beings have yet to evolve into a species that is incapable of acts of inhumanity. David Livingstone Smith’s book Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others offers us insight into the processes that lead to the designating of fellow human beings as ‘subhuman’ and makes possible the potential for human beings to perpetrate acts that can only be considered as evil.

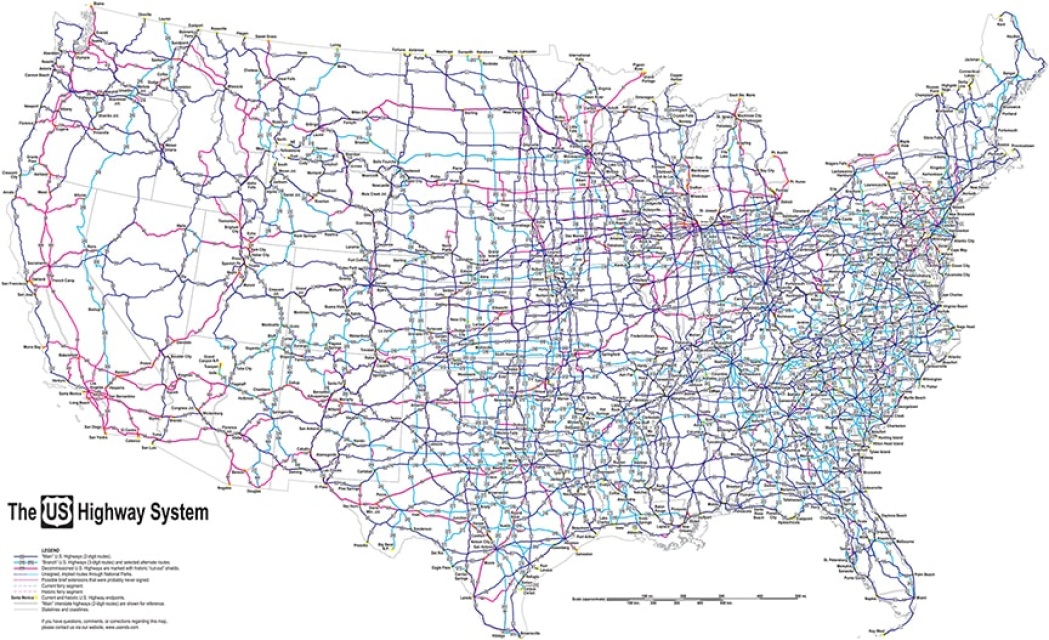

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.