by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by David Kordahl

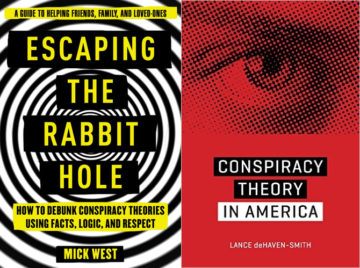

This is a post about conspiracy theories—yes, another one, after a year’s worth—but let’s start by remembering a benign old theory from a little over one year ago, back when ex-vice-president Joe Biden had won just one primary, down in South Carolina, where he had been aided by the endorsement of representative Jim Clyburn. At the end of February 2020, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren both led Biden in the national polls, with Michael Bloomberg, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar all not far behind.

Then, suddenly, everything fell into place. On March 1, Buttigieg announced that he would be dropping out, and on March 2, so did Klobuchar. Both appeared that night at rallies to endorse Biden. When Biden had an unexpected run of victories on March 3, Super Tuesday, the new narrative emerged. On March 4, Bloomberg dropped out and endorsed Biden. On March 5, when Warren dropped out, she withheld any endorsement. Many had expected her to endorse Sanders, but eventually she, too, endorsed Biden.

What had happened? At the time, pundits warned us not to fall into the trap of thinking anything was rigged. Here’s a Washington Post headline: “‘Rigged’ rhetoric makes comeback after Trump’s comments and Sanders’s losses—and gives Russia just what it wants.” And another from Vox: “The problem with saying the Democratic primary is ‘rigged’: An expert on actual election rigging debunks the conspiracy theory.” Early the next week, the Associated Press gave an inside report, based on claims from anonymous campaign operatives, that avoided any hint of collusion.

But there was a problem with this preemptive caution. So far as I can tell, despite all the strenuous arguing, these drop-outs were, in fact, rigged.

Naturally, Democratic insiders wouldn’t put it that way, but the new book Lucky: How Joe Biden Barely Won the Presidency, by Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes, inadvertently makes the case. When asked on the FiveThirtyEight Politics Podcast just how involved the Democratic party was in this process of encouraging Buttigieg and Klobuchar to drop out, Allen is unequivocal. “Yes, the party was very involved.” He recalls the worry of the Democratic establishment: that Bernie Sanders would win, and that the nomination would have to be taken away from him. Read more »

by Varun Gauri

In my last speech of my last high school debate round, at the finals of the Ohio championships, I claimed victory because our opponents, a team from the local private academy, our nemesis, neglected or “dropped” our argument that taxing cigarettes would certainly, absolutely, trigger nuclear war. Therefore, I declared, whatever you, dear judge, think of that argument or of our fast-talking style, a notorious debate technique known as “the spread,” there is no choice but to declare us winners. The rules of the game are binding.

“In the middle of the spread” are the last words of Ben Lerner’s widely acclaimed novel The Topeka School, which centers on a Kansas high school debater (Adam Gordon, seemingly a Lerner stand-in), as well as his partying friends, in the narrative retellings — de-centered, non-chronological, tense-shifting, montage-like — of his psychologist parents, his young debating self, a troubled family friend, and the debater as parent and “well-known poet,” who Lerner is. The primary thematic concern of the novel is the role of language in personal and public life. “A quote like that can save your life,” says the debater’s father, speaking of his colleague Klaus, whose family died in the Holocaust.

“The spread,” both a concentration and deformation of language, is a prominent image throughout this mesmerizing novel, standing in for the “thousands of generations technical progress” that make automobiles and other modern marvels possible, but also widespread alienation and predation in the modern world (“corporate persons deployed a version of the spread all the time”). Even poets will deliver “nonsense as if it made sense.” There appears to be an “instinct to spread,” given that language and culture, like the intermingling personal and professional relationships among the debater’s parents’ colleagues, commingle self-referentially, incestuously. They are quotation machines. For the person ensnared in the spread, “there is no outside, but one vast interior.” The novel, as it progresses, enacts the poetic spread by constructing an ever thicker, and continually illuminating, web of internal quotations and references. Some novels are praised for their “world building.” This novel is a hypnotizing feat of consciousness building. Read more »

by Chris Horner

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

The world we live in is changing, and our politics must change with it. We are in what has been called the ‘anthropocene’: the period in which human activity is threatening the ecosystem on which we all depend. Catastrophic climate change threatens our very survival. Yet our political class seems unable to take the necessary steps to avert it. Add to that the familiar and pressing problems of massive inequality, exploitation, systemic racism and job insecurity due to automation and the relocation of production to cheaper labour markets, and we have a truly global and multidimensional set of problems. It is one that our political masters seem unable to properly confront. Yet confront them they, and we, must. Such is the scale of the problem, the political order needs wholesale change, rather than the small, incremental reforms we have been taught are all that are practicable or desirable. And change, whether we like it or not is coming anyway: between authoritarian national conservative regimes, which with all the inequality, xenophobia, or that of a democratic, green post-capitalism. The thing that won’t survive is liberalism.

‘Liberalism’ is a notoriously hard term to pin down. But for the sake of clarity, I would just say that I am not using it in the sense that many in the USA do: as just the alternative to ‘conservatism’, the kind of thing the New York Times, the Democratic Party and so on might represent, a set of attitudes and policies contrasted with the kinds of things a Republican might might hold dear. Rather, I mean an entire political philosophy that most of those in both the aforementioned parties support, as well as those of no party at all. And this applies to most of the ‘centrist’ political parties in western Europe, Canada and Australia. So what is it? Read more »

by David Oates

A missing tradition is haunting us, though we may not even realize it’s missing. It was called “conservatism,” and in the Anglo-American political tradition it has a record of partnering with liberals to create some of our greatest moments of democratic progress.

Our new president did once publicly hope to govern under a new and restored regime of that legendary chimera “bipartisanship,” liberals and conservatives hammering out compromise bills that advance the public interest. But that fantasy has quickly faded. Even after the departure of the former president and his hateful ways, what’s left of the Republican party seems to be a beast of unqualified partisanship, angry, ravenous, utterly uncompromising.

This became obvious when the “Covid Relief Bill” had to be passed in the Senate with only Democratic votes. Yet it was almost self-evidently needed as a response to an unprecedented public crisis. It was beneficial enough for some Republicans to take credit for it in public . . . despite having voted against it.

Where is the GOP that is heir to, for instance, the conservatives who helped pass civil rights legislation and who founded the Environmental Protection Agency? Or heir to the British conservatives (Tories) who expanded the electorate and made the entire system broader, less class-based, more democratic? Plaintively we ask, where are the conservatives of old? Ay, where are they?

Replaced by reactionaries, every one. And this is not name-calling. It’s sober truth. The United States, as of this writing, has no conservative party. Probably hasn’t for a decade or more.

The grand Anglo-American tradition of careful conservatives offering measured reform and real progress has vanished from America. An apocalyptic trio has replaced them: resentment, revanchism, and reaction. With three “R’s,” alliterative, as if for a tidy little sermon. And I can’t help wondering: what is the sickness of soul that leads to such angry irrationality? Read more »

by Thomas Larson

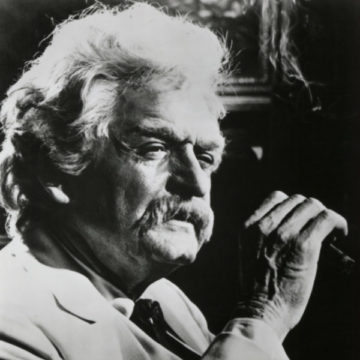

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, among the greatest and most widely read authors in history, is known everywhere by his pen name, Mark Twain. This was the nom de plume Clemens adopted in 1863 as a frontier columnist for The Virginian, a Nevada newspaper. There, he wrote satires and caricatures, bald hoaxes (fake news) and ironic stories of the wild pioneers he met and whose tales he embellished even further. His writerly persona came alive when he began lecturing and yarn spinning from a podium. Over time, his lowkey delivery, his deft timing, coupled with the wizened bumptiousness of a country orator in a white linen suit, captivated audiences in America and Europe, and on world tours. No one has embodied America, in its feral enthusiasms and its institutional hypocrisies, better than Clemens. Dying at 74 in 1910, he played Twain—rather, he became him—for 47 years.

In the early 1950s, a young actor from Cleveland, Ohio, Hal Holbrook, adopted the Twain persona for a stage act, aping the man’s appearance and cornpone speech and dipping into the goldmine of material—raucous tales to tell and witty saws to quip. Examples of the latter: “Dying man couldn’t make up his mind which place to go to—both had their advantages: Heaven for climate, Hell for company.” “Faith is believin’ what you know ain’t so.”

Holbrook developed the act before psychiatric patients, school kids, and Rotarians in the Midwest, then launched a polished performance in 1954 as “Mark Twain Tonight!” The stage: Lock Haven State Teachers College in Pennsylvania. Within a few years, he was on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “The Tonight Show.” He debuted Off-Broadway in 1959, the show hitting Broadway in 1966 when Holbrook won a Tony. He went on to play Clemens’s Twain more than 2000 times from 1954 to 2017 when he retired the act. A record, no doubt, for a single role: 63 years, a decade and a half longer than Clemens himself played Twain. Read more »

My friend Stephen Asma painted this oil portrait of Frederica Krüger at my request. I had just brought it home from the framer’s shop and propped it against a bookshelf in my office when Freddy arrived and proceeded to examine it very carefully. Then I asked her to turn around for a second and took this photo.

by Sabyn Javeri Jillani

Eve was thrown out of heaven because she was a temptress, Sita had a trial by fire because she crossed a line, Lot’s wife (who doesn’t even get a mention by her own name) was turned into a pillar of salt because she was disobedient, but Mary was a saint for giving birth as a virgin. Collectively, the one thing that binds these narratives is a sense of shame. But what if these stories about women were told to us from a different perspective? What if we were told that Eve was a pioneer and a risk-taker for indulging her curiosity about the forbidden fruit? Or that Sita was charitable and fearless for wanting to help an old man in need, Lot’s wife was a patriot and a freethinker for looking back at the land that had raised her, and that Mary was a courageous single mother. How would women see themselves if they grew up thinking of themselves as survivors and not as victims blamed for their choices and penalized for their actions or praised for their purity and silence? What if we saw women for who they are instead of who we want them to be? What if didn’t shame women?

Aib, sharam, haya, izzat, laaj, dishonour — almost every language has a word for shame. And the burden of that shame lies on the shoulders of the female. Because when we grow up in a culture which penalizes women for the consequences of their choices, we internalize a culture of shame — a culture of victim blaming that shames women for asserting their sexuality and agency, shaming them for raising their voices and scrutinizing their bodies. Women learn to curb their curiosity, to stifle desire, and to take ‘submissive and compliant’ as compliments.

As I saw the backlash against Pakistan’s Aurat (Women’s) March unfold this year, I was reminded of the politics of shame that so many women all over the world internalize. I found myself questioning… what does it mean to grow up knowing you are being watched? What does it mean to live in a voyeuristic bell jar where the collective weight of society determines the choices you make? When the length of your skirt can be responsible for your rape, when loving someone your family does not approve of can get you killed, when violence against you is tolerated and even justified because it is your fault that you could not understand the code of honor? From body shaming to slut shaming, the shame is all yours. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

Perseverance, the fifth NASA/JPL rover to land successfully on Mars, is currently looking for life there. What if it finds it?

The discovery of life on Mars would provide evidence that life is ubiquitous and likely to arise spontaneously under moderately favorable circumstances. It would be evidence that life everywhere is very similar – or, alternatively, very different – and give us more reason to suspect that there is life elsewhere in our own solar system. It could even suggest that we – you and I – are Martians. What evidence of life on Mars will not do, despite what some have argued, is make it more probable that human beings will go extinct. That last suggestion, proffered by Nick Bostrom and echoed by others, is (to use a technical, philosophical term) bonkers. So, I will leave it for last.

Perseverance is not just looking for life. It’s exploring the potential habitability of Mars for future missions, collecting samples that may be returned to Earth later, collecting instrument data, and taking spectacular photographs. I am excited about it as I have been excited about every mission since Viking 1 in 1976. (Excited, that is, once I recovered from my initial disappointment that there didn’t seem to be any dinosaurs on Mars. Don’t judge me. I was eleven years old.) But occasionally when I share my excitement with others, usually in the form of photographs, I get a dispiriting response. “It’s just a bunch of rocks,” more than one person has said to be. Either way, it’s still fascinating to me. But, well, maybe, it’s not just rocks. Maybe there is life on Mars.

For the purposes of this discussion, I am not going to distinguish between definitive evidence of past life and current, you know, actual life. Of course, it’s more exciting if there is actual respirating and metabolizing going on there right now. Fossils of extinct life are, well, still just rocks. But we are much more likely to find evidence of past life than anything living. To see why consider the question, why can’t we just see that there is or isn’t life on Mars? It looks pretty dead. Whereas a probe to Earth would detect life from orbit. Read more »

by Adele A. Wilby

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

Over recent times, many books have been published with the aim of writing women into history and crediting them for the achievements they have made to the benefit of humanity more broadly. Janice P. Nimura’s The Doctors Blackwell is in that genre of women’s history and she effectively narrates the biographies of the first two remarkable women to study and practice medicine in the United States: Elizabeth Blackwell and her younger sister, Emily.

In this modern world where the sky is literally the limit for women should they have the ambition, determination and the opportunity, it is sometimes difficult to think of them being stifled in such a way as to constrain their potential, yet that has been the plight of women throughout history, and indeed remains the situation for many women across the globe. Gender has been a crucial factor in defining the lives of women, probably exacting a terrible toll of lifelong intellectual frustration and stifling ambition for many of them. As Nimura’s book reveals, Elizabeth Blackwell, a ‘solitary, bookish, uncompromising high-minded’ young woman was one such woman, until she found her way into medicine. Read more »

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

Cynthia, let me begin by asking you to describe your path to the book—a double path that led you to Joseph Brodsky and to George L. Kline.

I studied with Joseph Brodsky at the University of Michigan—his first port of call in the U.S. It was psychological and aesthetic jolt, like sticking your finger into a light socket. And yes, we memorized hundreds of lines of poetry in his classes.

For many of us, Brodsky’s Selected Poems in 1973 was a radical reorganization of what poetry can be and mean in our times. However, I didn’t connect with the book’s translator, George Kline, until after I published Joseph Brodsky: Conversations in 2002. George and I stayed connected with Christmas cards and occasional phone calls. But we’d never actually met face to face—so I had no real sense of his age, until in late 2012, when he mentioned that he was almost 92.

George was a champion for Joseph Brodsky and his poetry—many people know that, but many don’t know that he was also a wise and kindly supporter of poets, Slavic scholars, and translators everywhere. He had never given a full account of his collaboration with the Russian-born Nobel poet, however, and I realized time was running out. So we began recording conversations.

His health was failing, and our talks became shorter and more infrequent. Towards the end, he urged me to augment our interviews with his articles, correspondence, and papers, reconstructing a portrait of his collaboration with Brodsky. George died in 2014. Read more »

by Charlie Huenemann

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

So perhaps the more accurate view is that many philosophers were swept up in the science craze along with so many others, and one way philosophers can demonstrate their excitement for something is by providing book-length justifications for it. Thus did it transpire that philosophers inclined toward logical empiricism tried to show how laws of nature were in fact based on nothing more than sense perceptions and logic — neither of which could anyone dispute. Perceptions P1, P2, … Pn, when conjoined with other perceptions and carefully indexed with respect to time, and then validly generalized into a universal proposition through some logical apparatus, lead indubitably to the conclusion that “undisturbed bodies maintain constant velocities” — you know, that sort of thing.

Alas, the justifications never quite worked. Philosophers are very clever, especially when it comes to exploiting logical loopholes with surprising counterexamples. And so were introduced, alongside the venerable problem of induction, new problems like the raven paradox, the grue problem, and other hijackings of the justifications provided for science. Rescue attempts were made, only to prompt new mutations of the initial problems. It began to look as if logic and sense perceptions may not be quite enough to establish the full rationality of science. Read more »

by Mike O’Brien

I have joked, mostly to myself, that if I ever wrote a memoir, it would be entitled “Never Gone Nowhere, Never Done Nothing: The Mike O’Brien story”. Such a lifestyle stands in near-total contraposition to that of Belén Fernández, at least in its status quo ante March 2020. Prior to that, she tells us, she had never spent more than a few months in the same place since leaving college. An American who goes to great lengths to avoid ever setting foot in America, she had arrived in Mexico on March 13 with the intention of setting off to yet another destination a few days later. Covid, of course, had other plans.

Her slim but dense (though never plodding) book, “Checkpoint Zipolite”, is a tale of forced stillness that stops her globe-trotting life in its tracks. The titular locale is, we are told, Mexico’s only clothing-optional beach, and carries the ominous and purportedly well-deserved nick-name of “Playa de la muerte“. Of course, mortality stalks around every corner in the age of Covid, so the “Beach of Death” might be as good a place as any to ride out a shelter-in-place-order. From my snowy Canadian suburb, it sounds downright idyllic.

The book is essentially a travel diary, woven through with frequent socio-political rants, personal reflections and historical factoids. There is a buzzing, over-active and effusive character to her life, her mind, and her writing, and when one outlet is blocked, it spills out through another. The repressed desire to travel is apparent in the daily minutiae (buying buckets, searching for yerba mate suppliers, negotiating space-sharing agreements with domestic insects) that serve as jumping-off points for recollections and rhetorical flights that span centuries and continents. Fernández’s life of incessant travel and political observation has provided ample material for weaving such connections, and though these digressions are conspicuous for their ubiquity, they don’t feel over-played. I could imagine many of the cited facts and events being replaced by equally poignant and entertaining substitutions from among Fernández’s own rich supply. Read more »

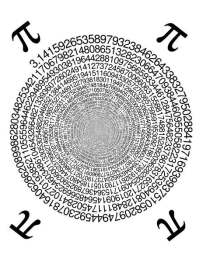

pi is perfection with a loose end

loose end

3 point 1 four and so on

without pattern or closure

the precision of a mandala

drawn by a drunk on three martinis

not describing wholeness merely

but thinking odd numbers

spouting them while rambling home

disheveled, irrational, unseemly

as the similar square root of 2

at the point of life and infinity

.

Jim Culleny

3/14/15

by Joan Harvey

For several years I enjoyed discussions about neuroscience with a friend (now deceased) who was a top rock climber. He and his buddies, when not performing solo climbs with torn shoulder muscles and sleeping on cliffside bivouacs, would listen to Sam Harris and talk neuroscience. We have conquered mountains, was their creed; now we will take on the mind. Because of this, and despite the fact that many top neuroscientists are women, and that many neuroscientists come across as gentle and balanced individuals, I got the idea of neuroscience as a slightly competitive macho sport. I grew up among mountains and as a young person I was fond of the Hopkins lines:

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed…

Men and women are now fathoming these mind cliffs and, here and there, claiming first ascents.

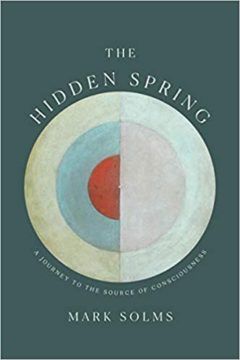

In the middle of his new book The Hidden Spring, Mark Solms quotes Einstein: “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.” This could describe the thinking behind The Hidden Spring: to make the complex theory within as simple as possible, without dumbing it down so much as to be meaningless. It’s an extraordinarily ambitious undertaking—on the one hand Solms is addressing the “hard problem” of consciousness with his own relatively controversial theory; on the other hand he’s trying to explain general concepts of science (falsifiability, Bayesian theory, the free energy principle, Markov blankets, etc.) to a reader who might not know them, so as to guide them through his thinking.

Solms is successful, to my mind, but there remains the question: Who is the general reader (I salute you, General Reader) to whom he says the book is addressed, and whom he advises to ignore the endnotes aimed at academics? I suppose I qualify as a General Reader, as I have neither a math nor a science background, though I did compulsively read all the endnotes. One needn’t be familiar with the arguments of Nagel and Chalmers or Andy Clark’s predictive processing, as Solms summarizes their arguments clearly; on the other hand it probably doesn’t hurt to have some background, and I suspect the “general” reader who comes to this book will do better with at least an acquaintance with these things. Read more »

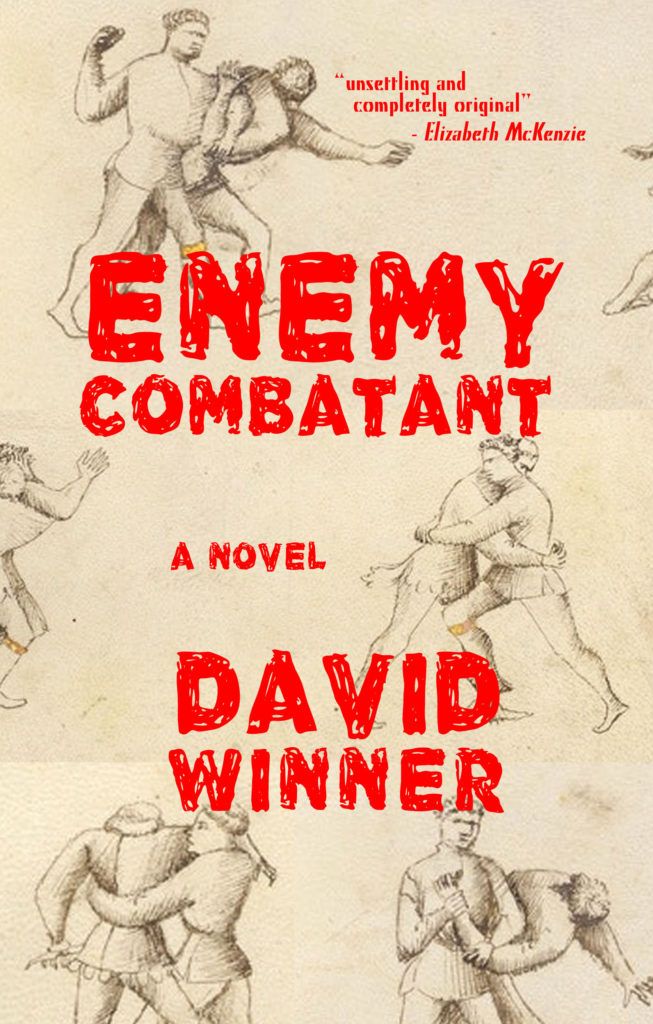

by Andrea Scrima

David Winner’s third novel, Enemy Combatant, has just been published by Outpost19 Books and has already received a starred Kirkus review. The book is an action-packed road trip gone horribly haywire, a misadventure mired in alcoholic debauchery and doomscrolling-induced moral indignation at the imperial arrogance of the Bush administration following 9/11. Sensitively and intelligently written, it wobbles between the tragic, comic, and utterly ridiculous as two close friends set out to free someone, anyone, from one of the extra-judicial black-op sites the US set up in the Caucasus and elsewhere and document the evidence. I spoke to David about some of the ideas behind his tragicomic page-turner.

Andrea Scrima: Your new novel, Enemy Combatant, looks back to the Bush era from a point in time still buckling under the enormous pressure of the Trump administration. Before the book even gets underway, we’re given a comparison between these two periods in recent American history: the stolen election of 2000, September 11 and the wars that followed, the reintroduction of enhanced interrogation and torture and, of course, the black-op sites you home in on in your novel—as opposed to kids in cages, half a million Covid deaths, withdrawing from the Paris Treaty and everything else the past administration was infamous for. Looking back over the past 20 years, what similarities do you see between these two periods, and what are the key differences?

David Winner: I don’t like using “neo-liberal” because it’s such a bogeyman term, but it comes in handy while describing the Bush years. There was a hawkish consensus in the United States, a thirst for blood, stemming from 9/11. It’s hard to separate Bush from both Clintons and Tony Blair as they, along with the “reliably liberal” New York Times and The New Yorker, all supported the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, which turned out to be a slippery slope to torture. Like the protagonist of Enemy Combatant, I was infuriated by the Bush administration, a fury that was aggravated by the sense of being part of a small minority whose conventional left-wing belief in the flawed history of American foreign policy didn’t get flipped around when the towers came down. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Crowing! Rwanda 2016.

Digital photograph.

by Thomas O’Dwyer

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a previous column: “Iris was my ‘first’ at age 15 – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also her first novel, published in 1954.” Time has moved on from Murdoch’s vanishing fictional worlds, from their now decrepit or deceased characters and their dated opinions. In recent decades we have been hovering on the fuzzy frontier of a strange near-future which many of us will not live to see clearly. Ishiguro seems to have a glimpse of it, and his vision leaves his readers both curious and queasy. Iris Murdoch can lead us, like Lawrence Durrell’s Justine, “link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together.” It’s a firm and familiar journey, remembering the foreign country of the past. Ishiguro is eerier — he seems to be forcing us to remember the future. It hasn’t arrived yet, but it already feels as familiar and uncomfortable as our own past mistakes.

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a previous column: “Iris was my ‘first’ at age 15 – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also her first novel, published in 1954.” Time has moved on from Murdoch’s vanishing fictional worlds, from their now decrepit or deceased characters and their dated opinions. In recent decades we have been hovering on the fuzzy frontier of a strange near-future which many of us will not live to see clearly. Ishiguro seems to have a glimpse of it, and his vision leaves his readers both curious and queasy. Iris Murdoch can lead us, like Lawrence Durrell’s Justine, “link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together.” It’s a firm and familiar journey, remembering the foreign country of the past. Ishiguro is eerier — he seems to be forcing us to remember the future. It hasn’t arrived yet, but it already feels as familiar and uncomfortable as our own past mistakes.

Ishiguro’s first novel was A Pale View of Hills, but the first I read was An Artist of the Floating World. Both dealt with post-war Japan, so, given his name and topics, I lazily assumed this was a new Japanese writer in translation. Was he perhaps someone who would transcend his native language and become an international star like Colombia’s Gabriel García Márquez or Portugal’s José Saramago? Of course, he was not. He’s more like an Iris Murdoch, a rare specimen of a quintessentially English writer who arrived in England from somewhere else and, like her, became British enough to be knighted by the Queen. Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki. When he was five, his scientist father accepted a research post in England at the National Institute of Oceanography. The family settled permanently at Guildford in Surrey. Ishiguro had a complete British education, from grammar school to Kent University and a creative writing master’s degree at East Anglia University. He published A Pale View of Hills in 1982, aged 28. Read more »

by Fabio Tollon

It is natural to assume that technological artifacts have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the designed properties of the artifact, but I will take a different approach. I will suggest that artifacts can come to embody values based on their affordances.

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the designed properties of the artifact, but I will take a different approach. I will suggest that artifacts can come to embody values based on their affordances.

Before doing so, however, I need to convince you that the instrumental view of technology is wrong. While some technological artifacts are perhaps merely instrumentally valuable, there are others that are clearly not so There are two ways to see this. First, just reflect on all the ways which technologies are just tools waiting to be used by us but are rather mediators in our experience of reality. Technological artifacts are no longer simply “out there” waiting to be used but are rather part of who we are (or at least, who we are becoming). Wearable technology (such as fitness trackers or smart watches) provides us with a stream of biometric information. This information changes the way in which we experience ourselves and the world around us. Bombarded with this information, we might use such technology to peer pressure ourselves into exercising (Apple allows you to get updates, beamed directly to your watch, of when your friends exercise. It is an open question whether this will encourage resentment from those who see their friends have run a marathon while they spent the day on the couch eating Ritter Sport.), or we might use it to stay up to date with the latest news (by enabling smart notifications). In either case, the point is that these technologies do not merely disclose the world “as it is” to us, but rather open up new aspects of the world, and thus come to mediate our experiences. Read more »

by Brooks Riley