Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, at night.

A day in the life of Kimono Mom and Sutan

by Bill Benzon

“I’m trying to treat her as an equal.”

– Moe, talking about Sutan

Of philosophy and food

Moe, the name has two syllables, is Moto’s wife and Sutan’s mother. Though it may also be a play on “a Japanese word that refers to feelings of strong affection mainly towards characters in anime, manga, video games, and other media [and] has also gained usage to refer to feelings of affection towards any subject.”

“Tan” is an honorific, roughly meaning small, and is used with babies, though I would say that Sutan is more a toddler at this point than a baby – at least in the usage common in my own (American) culture. She was a baby of 10 months when Moe started making Kimono Mom videos.

Moto, then, is Moe’s husband and Sutan’s father. When Moe started making her Kimono Mom videos Moto worked in the restaurant and hospitality business. But now he is business manager and partner in Moe’s YouTube business, which is centered on Japanese home cooking. And on Sutan.

Kimono Mom, though, is a cooking show in the way that Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown was a food and cooking show. Yes, Bourdain traveled all over the world and showed us the food of many different cultures. But he used food as a vehicle for revealing and reveling in human diversity, for talking philosophy in plain language, for fun. Think of Kimono Mom as a philosopher with Sutan as her Socrates. She uses the cooking video the way Plato used the dialog form. It’s a vehicle.

Let’s walk through the video at the head of this article. (When watching the video be sure to click the “cc” button at the lower right. That will give you English language captions for people’s speech. You can set the language with this settings menu, the small “gear” to the right of cc.)

Moe, Sutan, Moto.

Sutan, Moto, Moe.

Moto, Moe, Sutan.

Monday, January 23, 2023

A horror show of technological and moral failure

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

“Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo and the Road to the Atomic Bomb”, by James M. Scott

On the night of March 9, 1945, almost 300 B-29 bombers took off from Tinian Island near Japan. Over the next six hours, 100,000 civilians in Tokyo were burnt to death, more possibly than in any six hour period in history. James Scott’s “Black Snow” tells the story of this horrific event which was both a technological and a moral failure. It is also the story of how moral failures can result from technological failures, a lesson that we should take to heart in an age when we understand technology less and less and morality perhaps even lesser.

The technological failure in Scott’s story is the failure of the most expensive technological project in World War 2, the B-29 bomber. The United States spent more than $3 billion on developing this wonder of modern technology, more than on the Manhattan Project. Soaring at 30,000 feet like an impregnable iron eagle, the B-29 was supposed to drop bombs with pinpoint precision on German and Japanese factories producing military hardware.

This precision bombing was considered not only a technological achievement but a moral one. Starting with Roosevelt’s plea in 1939 after the Germans invaded Poland and started the war, it was the United States’s policy not to indiscriminately bomb civilians. The preferred way, the moral way, was to do precision bombing during daytime rather than carpet bombing during nighttime. When the British, led by Arthur “Butcher” Harris, resorted to nighttime bombing using incendiaries, it was a moral watershed. Notoriously, in Hamburg in 1943 and Dresden in 1944, the British took advantage of the massive, large-scale fires caused by incendiaries to burn tens of thousands of civilians to death. Read more »

If the Medium is the Message, What is the Message of the Internet?

by Tim Sommers

What’s the greatest prediction of all time?

By “greatest,” I mean something like how big a deal the thing predicted is multiplied by how accurate the prediction was. I would love to hear other proposals in the comments, but mine is Andy Warhol’s prediction that, “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.”

It was made somewhere around 1968. Not only were there no social media and no internet at the time, but computers were barely even a thing. Could you have looked around at celebrity culture in 1968 and predicted Instagram and Twitter and influencers?

Yes, I know. Many doubt that Warhol said this. Wikipedia, for example, baldly asserts that this quote is “misattributed” to Warhol, while the Smithsonian Magazine more judiciously reports that he “probably never said” that. But I don’t think the evidence that they cite really confirms their skepticism. The Smithsonian Magazine, for example, reports that art critic Blake Gopnik (never even mentioned as one of the suspects in the Wikipedia article) claimed credit for the quote, and then they take it as confirmation of Gopnik’s story that later on Gopnik also said that he (Gopnik) heard Warhol say that he (Warhol) never said that. It’s like Wittgenstein’s example of someone trying to confirm what’s in the newspaper by buying a second copy of the same newspaper. Yoko Ono, John Lennon, and David Bowie all credit the quote to Warhol. That’s good enough for me.

On the other hand, maybe the fact that it’s hard to figure out to whom to attribute the quote, works better for our subject. Which is this. ‘If the medium is the message,’ as media theorist Marshall Mcluhan said, ‘what is the message of the internet as a medium?’ (Mcluhan, despite being an academic, became so widely recognize, largely for that line, that he did a cameo as himself in Annie Hall.)

My philosophy training forces me to begin by saying that I think Mcluhan should have said, ‘The medium of any particular media technology is itself also itself a kind of message in addition to the particular messages merely conveyed by that medium…” (Or something like that.)

Anyway, what is the message of the internet as a medium? The techno Utopian message of the internet, according to early enthusiasts, is that, “Information wants to be free.” Unfortunately, that’s wrong. The real message of the internet is, “All information is equal.” Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

Digital photograph.

Is Human Suffering Metaphysical or Mundane?

by Dwight Furrow

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

According to existentialism, as the role of God in modern life receded to be replaced by a secular, scientifically-informed view of reality, the resulting loss of a transcendent moral framework has left us bereft of moral guidance leading to anxiety and anguish. The smallness of human concerns in a vast, uncaring universe engenders a sense that life is inherently meaningless and absurd. There seems to be no ultimate purpose in life. Thus, our individual intentions are without foundation.

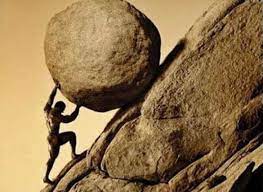

As Camus wrote:

The absurd is born in this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world. (From the Myth of Sisyphus)

And so, for Camus, human suffering is like the toils of Sisyphus condemned to endlessly roll the boulder up the mountain only to have it roll down again—life is a series of meaningless tasks and then you die.

Sartre, for his part, argued that the demise of a theistic world view means we must now confront the incontrovertible fact of human freedom—no state of affairs can cause us to act in one way rather than another. Furthermore, there are no values that have a claim on us prior to our choosing them. Instead, at each moment, we make a choice about the significance of facts and our relation to them. If life is to be meaningful, we must invent that meaning for ourselves. We are thus “condemned” to be free and must take full responsibility for our actions and the meaning we attribute to them. Read more »

Iceland and the Reverend Egilsson

by Eric Bies

Jules Verne sent Lidenbrock and Axel over—to crawl down the throat of a dormant volcano.

W. H. Auden visited between wars and found the place wanting for souvenirs. “Of course,” he wrote, “one can always bring home little bits of lava for one’s friends—I saw the Manchester school-teachers doing this at the Great Geysir—but I am afraid I have the wrong sort of friends.”

William Morris went twice: once in 1871, again in 1873. To what purpose he did, his daughter, May, elucidates in her introduction to the Journals he kept during those journeys:

not to shoot their moors and fish their rivers but to make pilgrimage to the homes of Gunnar and Njal, to muse on the Hill of Laws, to thread his way round the historic steads on the Western firths, to penetrate the desert heaths where their outlaws had lived…. The whole land teems with the story of the past—mostly unmarked by sign or stone but written in men’s minds and hearts.

In the summer of 1627, a decade after the death of Shakespeare, a trio of ships appeared off the southern coast of Vestmannaeyjar. The people of the island—the Einars, Helgis, Gudrids, and Sigrúns—assisted by nearly eighteen hours of sunlight, kept their eyes fixed on the horizon for close to an entire day, during which they convened and debated; they watched and waited, weighing their options. In the end, they threw up a meager bulwark of stone and went to bed.

The following day, just when it seemed they could stand the menacing presence no longer, the ships dispatched a fleet of boats: then the boats disgorged a mass of men ashore—pirates—who descended on the town with spears drawn. Those who were quick on their feet managed to flee over hills and down through the caves that dotted the erupted landscape. The rest were captured or killed. Among the former was a man in his sixties, the Reverend Olafur Egilsson, who was taken together with his wife and children. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Things to Come: See, Hear and Read in 2023

by Chris Horner

A look forward, and backward, to some ‘cultural stuff’ for the coming year, old and new things worth seeing, hearing or reading. Here we go:

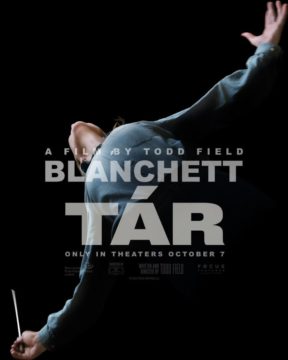

Tár.

Unless you have been cut off from all media in the last few months, you probably will have heard of this new movie from Todd Fields. Cate Blanchett plays Lydia Tár, star conductor in the Berlin Philharmonic. She has a lifestyle of the celebrity conductor and as wee see her prepare to record Mahler’s 5th symphony we also see her life beginning to fall apart. It turns out she is not immune to the temptations of power that go with the role of Maestro.

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly). Read more »

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly). Read more »

Confession

by Ethan Seavey

“Sometimes, before I take a piss, I spit into the toilet as a sacrifice to a false idol.”

The priest nods. He’s heard this one before. He was somewhere else before. Now he’s a resident of the confessional inside the attic of the home inside my head.

“I’m gravely concerned about coyotes, how easily they’re conquering the foxes, and the wolves, and how they’ll soon fill every niche humans have left in their wake. But I do nothing about it.”

He pulls his face closer to the wood surrounding the meshy grate, and inhales. The confessional’s distinct smell, that of a cedar box baking in the moist heat of an Illinois summer, hangs in the air, as thick as the tension between listener and listened to.

“Once, I had this dream—I was driving a car down the road, and then I just opened the door and stepped outside, leaving the car running, in drive. I watched it run 15 feet forward, running head-on into another car.”

Dreams are not sins.

“But I remember feeling no remorse.”

Before my family home was our home, it was a convent, and before that, it was a farmhouse. It hasn’t seen many renovations. I’ve spent years learning which of the aged floorboards creak, which doors squeak, and which of the fireplaces actually provide heat. My father tells guests that the original electric fireplace used to be a symbol of wealth. (A technological marvel! Who wants to sit around the standstill flames of the retro-future?)

Now they’re just tacky. Read more »

Monday Photo

Caught in the Middle of Intermediate Hindi

by Claire Chambers

In my last blog post I wrote about starting to learn the Hindi language during the pandemic. I embarked on this linguistic journey partly from a sense I didn’t fit into my own culture – or, equally, that English culture wasn’t the right fit for me. The sociologist Edward Shils wrote in 1961 about pre-Second World War visitors returning to their South Asian lands after a long time in Britain only to feel a ‘lostness at home and homesickness for a foreign country’. This is something I can recognize, albeit in the opposite direction.

In my last blog post I wrote about starting to learn the Hindi language during the pandemic. I embarked on this linguistic journey partly from a sense I didn’t fit into my own culture – or, equally, that English culture wasn’t the right fit for me. The sociologist Edward Shils wrote in 1961 about pre-Second World War visitors returning to their South Asian lands after a long time in Britain only to feel a ‘lostness at home and homesickness for a foreign country’. This is something I can recognize, albeit in the opposite direction.

As I became an intermediate learner, it felt as though my progress was glacially slow. In the early stage, every new word is a milestone. Yet once a solid linguistic framework already exists, forward momentum may be hard to discern. The learner can no longer see the yardsticks measuring progress as easily as they could at the outset.

The beginner may have a blithe innocence about the size of their task. However, the more you know, the more you realize you don’t know. I read somewhere, on the Berlitz website perhaps, that it takes five years to learn a language. It depends on what you mean by learn. Almost three years in by now, I would question that cheery five-year prognosis. I am caught in the middle of a process that feels never-ending. Read more »

Changing the Definition of “Woman”: Patriotism and How Dictionaries Work

by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

Lexicographers—the people who put together the dictionaries—care more about words than most of us. Of late, they’ve noticed how their beloved definitions have been abused by conservatives, and now a few have struck back. On December 13, the Cambridge Dictionary broadened their definitions of “man” and “woman” to include people who identify as either.

The original definition of “woman”: an adult female human being.

The new addition to the definition: an adult who lives and identifies as female though they may have been said to have a different sex at birth.

Losing their gotcha question infuriated conservatives. Fox News howled that “this change was met with pushback from many, who argued that redefining society’s categorization of gender and sex is harmful and inaccurate.” Dan McLaughlin, a senior writer at National Review called the change Orwellian: “1984 wasn’t supposed to be a how-to manual,” he tweeted.

Unfortunately for conservatives, they’re wrong. That is precisely how dictionaries are supposed to work. Dictionaries have always been political documents. For that, we have a Founding Father to thank. Read more »

Monday, January 16, 2023

Artificial Intelligence (sic) Forever Inanimate and Dumb; or Zenon Pylyshyn’s Cold-Cut Revenge (sic)

by David J. Lobina

A provocative title, perhaps, but as the sort-of cognitive scientist that I am, I find most of the stuff that is published about Artificial Intelligence (sic) these days, especially in the popular press, enough to make one scream, so perhaps some contrarian views on the matter are not entirely uncalled for. And in any case, what the title of the post conveys is more or less correct, though to be more precise, and certainly less bombastic, the point I want to make is that it is really a moot question whether modern AI algorithms can be sentient or sapient.

So. What sort of coverage can make one scream, then? Anything these days, especially since the release of GPT-3, let alone ChatGPT (and God help us when GPT-4 comes out), the large language models (LLMs) so popular these days, which are ever so often claimed to have matched the linguistic, and even cognitive, skills of human beings. This is not a new claim, of course; in 2019 there were already articles out there arguing that AI had not only surpassed human performance on rule-based games like chess, which at the very highest level of play involve carrying out huge numbers of calculations, thereby constituting the right sort of task for a computer, but also in terms of human understanding.

The situation is much worse now, though. LLMs will spell doom for certain professions, it seems, including university lecturers; or at least it will bring an end to all those dodgy companies that provide essay-writing services to students for a fee, though in the process this might create an industry of AI tools to identify LLM-generated essays, a loop that is clearly vicious (and some scholars have started including ChatGPT as a contributing author in their publications!). LLMs have apparently made passing the Turing Test boring, and challenges from cognitive scientists regarding this or that property of human cognition to be modelled have been progressively met.[i] Indeed, some philosophers have even taken it for granted that the very existence of ChatGPT casts doubt on the validity of Noam Chomsky’s Universal Grammar hypothesis (Papineau, I’m looking at you in the Comments sections here). We have even been told that ChatGPT can show a more developed moral sense than the current US Supreme Court. And of course the New York Times will publish rather hysterical pieces about LLMs every other week (with saner pieces about AI doom thrown in every so often too; see this a propos of the last point). Read more »

Trivia Pursuit

by Deanna K. Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory. [1] I’m not sure if it’s photographic or “eidetic” (which apparently is the official-ish scientific term)—I’ve never had the experience of seeing an entire page of text in my mind’s eye and then literally reading it off, for example. It’s more like all the words are in my head, similar to a regular memory but much more detailed, and I can simply retrieve them. The range of things I can remember this way is selective: it doesn’t work for everything, and I need to concentrate (in other words, care) in order to be able to do it. But my powers of recall under certain circumstances are sideshow-level freaky. I’ve always been obnoxiously proud of this ability, which is ridiculous when you think about it—having unusual powers of recall is no different from being tall or color-blind or right-handed. And yet for some reason most people (myself included) are fascinated by this so-called “skill.”

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory. [1] I’m not sure if it’s photographic or “eidetic” (which apparently is the official-ish scientific term)—I’ve never had the experience of seeing an entire page of text in my mind’s eye and then literally reading it off, for example. It’s more like all the words are in my head, similar to a regular memory but much more detailed, and I can simply retrieve them. The range of things I can remember this way is selective: it doesn’t work for everything, and I need to concentrate (in other words, care) in order to be able to do it. But my powers of recall under certain circumstances are sideshow-level freaky. I’ve always been obnoxiously proud of this ability, which is ridiculous when you think about it—having unusual powers of recall is no different from being tall or color-blind or right-handed. And yet for some reason most people (myself included) are fascinated by this so-called “skill.”

A number of years ago, when I was still teaching at UBC, I saw an ad on a campus billboard for subjects for a memory experiment, and I jumped at the chance to show off. The experiment was a day-long affair: subjects would first have an MRI done of their brains, then do a bunch of memory tests, be given lunch, and then come back for more tests. I was interested in getting the MRI as well as the opportunity to showboat: as a semi-professional hypochondriac, I’m always happy to undergo free tests that will reassure me I don’t have a life-threatening tumor. Read more »

Monday Poem

The Hindu image of Anantashayana portrays the god Vishnu

reclining upon a coiled snake upon a raft floating in a sea of milk

dreaming up the universe

Until the Sacred Cows Come Home

Vishnu reclines and sleeps

dreaming up the world

…………………………..

He lounges upon a coiled snake

in the image of ananta shayana

floating on a raft

upon an ocean of milk

pacifying the characters of his dreams,

protecting his turf: his realm of

pleasure and pain; concocting

his improbable dream of a universe,

making it up as he goes

Here and there Vishnu floats

in the logic of dreams

sailing his ship of tales

–at sea but ever in sight of land;

singing, mything, pointing

he goes dreaming on,

sailing and sinking simultaneously;

doing and undoing his work at once

within the same thought,

bobbing on waves of light

while flinging its particles

into black holes

But he is never fickle.

Vishnu can never be fickle

because he’s divine

Any ordinary Joe or Ananda

would be ridiculed for insisting yes

and no in the same breath,

but not Vishnu

All Gods may contradict themselves

without flaw,

say men

(who always give their God

the benefit of a doubt

in any argument)

Faults may never be divine;

not earthquake or plague,

and especially not

the death-rattle of love

So Vishnu will sail on

upon his coiled snake,

upon his raft,

upon his ocean of milk,

with his sidekicks Brahma and Shiva

managing the staysail and jib,

dreaming, thinking, uttering

without pause, forever,

or until the sacred cows come home

and the last man disappears

–whichever comes first

Jim Culleny

2009

Restoring Eden: Our Long Journey to Recover American Lands

by Mark Harvey

If you submitted yourself to the idiotic torture over last week’s battle to elect the speaker of the house for the 118th Congress, then you deserve a break from that idiocy and the chance to think about something else. American politics at the national level make toxic uranium dumps seem like tea gardens. The petulance and pettiness of many of our politicians make daycare centers seem like bastions of diplomatic protocol.

But there are things to think about in this great land that are a salve and rampart against the most cretinous of our congresspersons: the many efforts of Americans to steward lands back to health.

Let’s not mince words: in a few hundred years on this continent, we have trashed millions of acres and imperiled thousands of species. From Seattle to Tampa, from Galveston to Fargo, and even in parts of Alaska, what we’re facing is the aftermath of a resource-eating orgy. Now we face the unpleasant hangover and picking up all the broken bottles. But some Americans with pluck, eternal optimism, can-do, and deep allegiance to the land are doing it. Read more »

The Federal Reserve’s Civilian Casualties

by Varun Gauri

When the Federal Reserve Bank raises interest rates to fight inflation, rates rise worldwide, and debts in developing countries become more difficult to service. The consequences for low-income countries can be severe. For instance, When Paul Volcker decided in the early 1980s to push the prime rate over 20%, he triggered a debt crisis in the developing world, causing catastrophic unemployment and poverty. The impact on Latin America exceeded that of the Great Depression, and was by some measures the worst financial disaster the world has ever seen. The ensuing cascade of poverty across Africa coincided with the emerging HIV/AIDS crisis, causing widespread misery. For instance, life expectancy, usually rising in the modern world, went, in Zimbabwe, from 61 years in 1984 to 48 years in 1997 (the interest rate shock was not the only cause). As historians note, a similar dynamic had played out in the 1920s, when the world’s main central banks raised interest rates, causing the price of grains and energy to become unaffordable for millions in colonies and low-income countries.

The practice continues. Recently, the covid pandemic, inflation, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have pushed an estimated 75 million people into poverty. In this context, the Fed has been raising interest rates to bring down a mix of demand-led inflation, rooted in sectoral imbalances following the covid crisis, and supply-shock inflation, arising from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Fed’s aggressiveness is perilous for the poorest people in the world, and the warning signs of developing country debt crises are again flashing. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Featherweights and Heavyweights: Curious Extremes in Avian Evolution

by David Greer

There’s a bird that weighs no more than an average paper clip and is one of the fiercest fliers on the planet. There once was a bird that weighed around half a ton, the same as an average cow, and laid an egg as large as 150 chicken eggs. The elephant bird is long gone but the bee hummingbird remains fighting fit. The only dinosaurs to survive the last mass extinction sixty-six million years ago, birds have evolved since then to fit into every available ecological niche, and today are the most widely distributed form of life on the planet other than microscopic organisms.

Birds are fascinating for any number of reasons, not least because of the mind-boggling variations in size that evolved through the tens of millions of years before humans stumbled onto the planetary stage. For the most part, the large flightless birds had been driven to extinction as humans spread across the planet, and close to two hundred other bird species are believed to have made their final exit during the last five hundred years as humans have largely converted the natural world to serve their own purposes during the latest geological epoch, the Anthropocene. Read more »