Photo of a lamp in Vahrn, South Tyrol, taken from a friend’s balcony.

A Montreal Bagel In Zurich

by Rafaël Newman

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

In the 1960s, when I was a boy growing up on the west side of Montreal, whenever my father needed a hit of soul food — a smoked-meat sandwich, some pickled herring, or a ball of chopped liver with grivenes—he would head east (northeast, really, in my hometown’s skewed-grid street plan) to his old neighborhood on the Plateau. He would make for Schwartz’s, or Waldman’s, to the shops lining boulevard St.-Laurent, once known as “the Main” in memory of its service as a major artery through the Jewish part of town before the district changed hands: or rather, reverted to majority rule. On weekends my father would travel a little farther, in the direction of Mile End, to either of two places, St. Viateur Bagels and Fairmount Bagels, each located on the street from which it took its name and each, as its name candidly proposed, a baker and purveyor of bagels.

My father’s parents were from Eastern Europe, born and raised in territories still administered by the Czar at the time of their births. They emigrated separately to Canada in the 1920s, fleeing economic ruin (in my Zaideh’s case) and Cossacks (in my Bubbi’s). Together with their birth families, and as yet unknown to each other, the two of them made it to Montreal, in those days the largest city in the Dominion and among the international goals of choice for people on the move. Read more »

On the Road: Tanzania to Zambia by Train

by Bill Murray

We left last month’s column worried about getting tickets on a train across a swath of Africa’s midsection, from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania to Lusaka, Zambia. There’s a funny system for getting on that train. You can reserve tickets over the phone but you can’t buy them online.

You must come to the train station in person, Tanzanian Shillings in hand, and buy your tickets with cash. When we turned up the day before departure, the whole, massive, foreboding station was deserted except for a sprinkle of porters loitering outside for lack of business, and one man behind the ticket window.

We offered our $188 in cash in shillings. He offered a big smile, the fact that he had a son in Missouri, and four tickets, so that the two of us, my wife Mirja and I, claimed an entire four person compartment for our own.

There is a cliché about Africa, about the need to build in extra time for everything. It’s a cutesy, knowing, slightly smug expression of superiority among tourists when they learn it and use it for the first time; it is, in fairness, also true.

Welcome to the Tazara (TA for Tanzania, ZA for Zambia and RA for railroad) railroad. Its timetable led us to expect a forty two hour ride, but we stayed on that train for fifty seven hours and forty minutes, busting through a scheduled Sunday morning arrival time and instead arriving after midnight the next day.

Not that you’d have thought so at the start. Remarkably, even a touch triumphantly, the Tazara pulled out of Dar es Salaam station three minutes late at 3:53 on Friday afternoon. It didn’t take long for its true character to emerge, though; the Tazara was three hours late by its second stop. Read more »

Monday, April 17, 2023

Building a Dyson sphere using ChatGPT

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

In 1960, physicist Freeman Dyson published a paper in the journal Science describing how a technologically advanced civilization would make its presence known. Dyson’s assumption was that whether an advanced civilization signals its intelligence or hides it from us, it would not be able to hide the one thing that’s essential for any civilization to grow – energy. Advanced civilizations would likely try to capture all the energy of their star to grow.

For doing this, borrowing an idea from Olaf Stapledon, Dyson imagined the civilization taking apart a number of the planets and other material in their solar system to build a shell of material that would fully enclose their planet, thus capturing far more of the heat than what they could otherwise. This energy-capturing sphere would radiate its enormous waste heat out in the infrared spectrum. So one way to find out alien civilizations would be to look for signatures of this infrared radiation in space. Since then these giant spheres – later sometimes imagined as distributed panels rather than single continuous shells – that can be constructed by advanced civilizations to capture their star’s energy have become known as Dyson spheres. They have been featured in science fiction books and TV shows including Star Trek.

I asked AI engine chatGPT to build me a hypothetical 2 meter thick Dyson sphere at a distance of 2 AU (~300 million kilometers). I wanted to see how efficiently chatGPT harnesses information from the internet to give me specifics and how well its large language model (LLM) of computation understood what I was saying. Read more »

Monday Poem

Graduations

I have before me a list of extensions

without names. But it seems not to go on forever,

because of horizon which, with

the slickness of a blade, a knife of

limitation, slashes time in two

I’ve ticked-off the list through many graduations,

sometimes with honors, sometimes

smeared against a wall of dreams since I’m

a creature of their reckless persistence,

their humiliations

But that irresistible incision far off, though closer now,

still draws me regardless of my self-shaped limitations,

my turnings from what is true

Jim Culleny, 4/16/23

On the Importance of Community

by Jonathan Kujawa

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are Jeff Goldblum — a category of its own. While it is true that doing mathematics involves a certain amount of thinking alone, I’ve frequently argued here at 3QD that math is a fundamentally social endeavor.

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are Jeff Goldblum — a category of its own. While it is true that doing mathematics involves a certain amount of thinking alone, I’ve frequently argued here at 3QD that math is a fundamentally social endeavor.

This weekend I was reminded again of this fundamental fact. Now that we are emerging from covid, in-person math conferences have returned in abundance. I am currently in Cincinnati attending one of the American Mathematical Society’s regional math conferences. It has been wonderful to hear many great talks about cutting edge research. The real treat, though, is the chance to see old friends and meet new people, especially the grad students and young researchers who’ve come into the field in the last few years.

In chats between talks, you learn about the problems people are pondering; their private shortcuts to how to think about certain topics; how their universities handle teaching, budgets, and post-covid life; and, of course, the latest professional gossip. It is nice to be reminded that you are part of a community of like-minded folks.

One of the tentpole events of the conference was the Einstein Public Lecture. They are held annually at one of the AMS meetings and were started to celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of Albert Einstein’s annus mirabilis. In this case, the speaker was Nathaniel Whitaker, a University of Massachusetts, Amherst, professor. While the mathematical topic of his presentation was his work on finding approximate solutions and numerical estimates to the sorts of partial differential equations which arise in the study of fluid flows, the real story he wanted to tell was his journey from the segregated schools of 1950s Virginia to his role in the 2020s as a leader of a large research university [1]. Read more »

Activism or Aestheticism: Art in the Anthropocene

by Ethan Seavey

In the growing sector of the contemporary art world which focuses on environmental issues, participants in the art (artists, critics, and the general audience) disagree on the intention of each work of art: does it merit only aesthetic praise, or is it a successful work of climate activism? In my brief internship at Art of Change 21, a French nonprofit association at the intersection of contemporary art and the environment, I frequently encountered this dichotomy. At Art Paris 2022, the association hosted an exhibition centered around artists who deal with environmental themes. My goal is to contextualize some of the artworks present at this exhibition, based on critical theory as well as my own experiences.

When an artist depicts an environmental issue, they want to bring attention to it, and for many in the art world, this attention is enough to be considered powerful activism. In a study for the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Laura Kim Sommer and Christian Andreas Klöckner collected qualitative date based on surveys and cognitive recognition information and determined that art engaging with environmental issues had strong emotional effects upon its audience. This study was conducted at the 2015 UN Climate Conference, for an exhibition of art pertaining to climate issues. (Art of Change 21 was born at this Climate Conference, and had no role in the display of these artworks; the association was present elsewhere in the conference, though, with similar projects.) Read more »

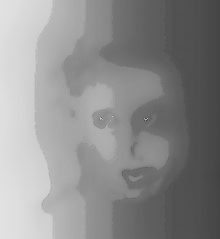

Perceptions

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

Digital photograph.

With permission.

The Myth of Free Thinking

by Chris Horner

The illusion of rational autonomy

The world is full of people who think that they think for themselves. Free thinkers and sceptics, they imagine themselves as emancipated from imprisoning beliefs. Yet most of what they, and you, know comes not from direct experience or through figuring it out for oneself, but from unknown others. Take science, for instance. What do you think you actually know? That the moon affects the tides? Something about space-time continuum or the exciting stuff about quantum mechanics? Or maybe the research on viruses and vaccines? Chances are whatever you know you have taken on trust – even, or particularly, if you are a reader of popular science books. This also applies to most scientists, since they usually only know what is going on in their own field of research. The range of things we call ‘science’ is simply too vast for anyone to have knowledge in any other way.

We are confronted by a series of fields of research, experimentation and application: complex and specialised fields that requires years of study and training to fully understand. As individuals, we cannot be experts in all scientific domains, which is why we typically rely on the knowledge and expertise of the scientific community, composed of experts from various fields who have the necessary background knowledge, experience, and expertise to evaluate scientific theories and data accurately. Read more »

Artificial General What?

by Tim Sommers

One thing that Elon Musk and Bill Gates have in common, besides being two of the five richest people in the world, is that they both believe that there is a very serious risk that an AI more intelligent than them – and, so, more intelligent than you and I, obviously – will one day take over, or destroy, the world. This makes sense because in our society how smart you are is well-known to be the best predictor of how successful and powerful you will become. But, you may have noticed, it’s not only the richest people in the world that worry about an AI apocalypse. One of the “Godfathers of AI,” Geoff Hinton recently said “It’s not inconceivable” that AI will wipe out humanity. In a response linked to by 3 Quarks Daily, Gary Marcus, a neuroscientist and founder of a machine learning company, asked whether the advantages of AI were sufficient for us to accept a 1% chance of extinction. This question struck me as eerily familiar.

Do you remember who offered this advice? “Even if there’s a 1% chance of the unimaginable coming due, act as it is a certainty.”

That would be Dick Cheney as quoted by Ron Suskin in “The One Percent Doctrine.” Many regard this as the line of thinking that led to the Iraq invasion. If anything, that’s an insufficiently cynical interpretation of the motives behind an invasion that killed between three hundred thousand and a million people and found no weapons of mass destruction. But there is a lesson there. Besides the fact that “inconceivable” need not mean 1% – but might mean a one following a googolplex of zeroes [.0….01%] – trying to react to every one-percent probable threat may not be a good idea. Therapists have a word for this. It’s called “catastrophizing.” I know, I know, even if you are catastrophizing, we still might be on the brink of catastrophe. “The decline and fall of everything is our daily dread,” Saul Bellow said. So, let’s look at the basic story that AI doomsayers tell. Read more »

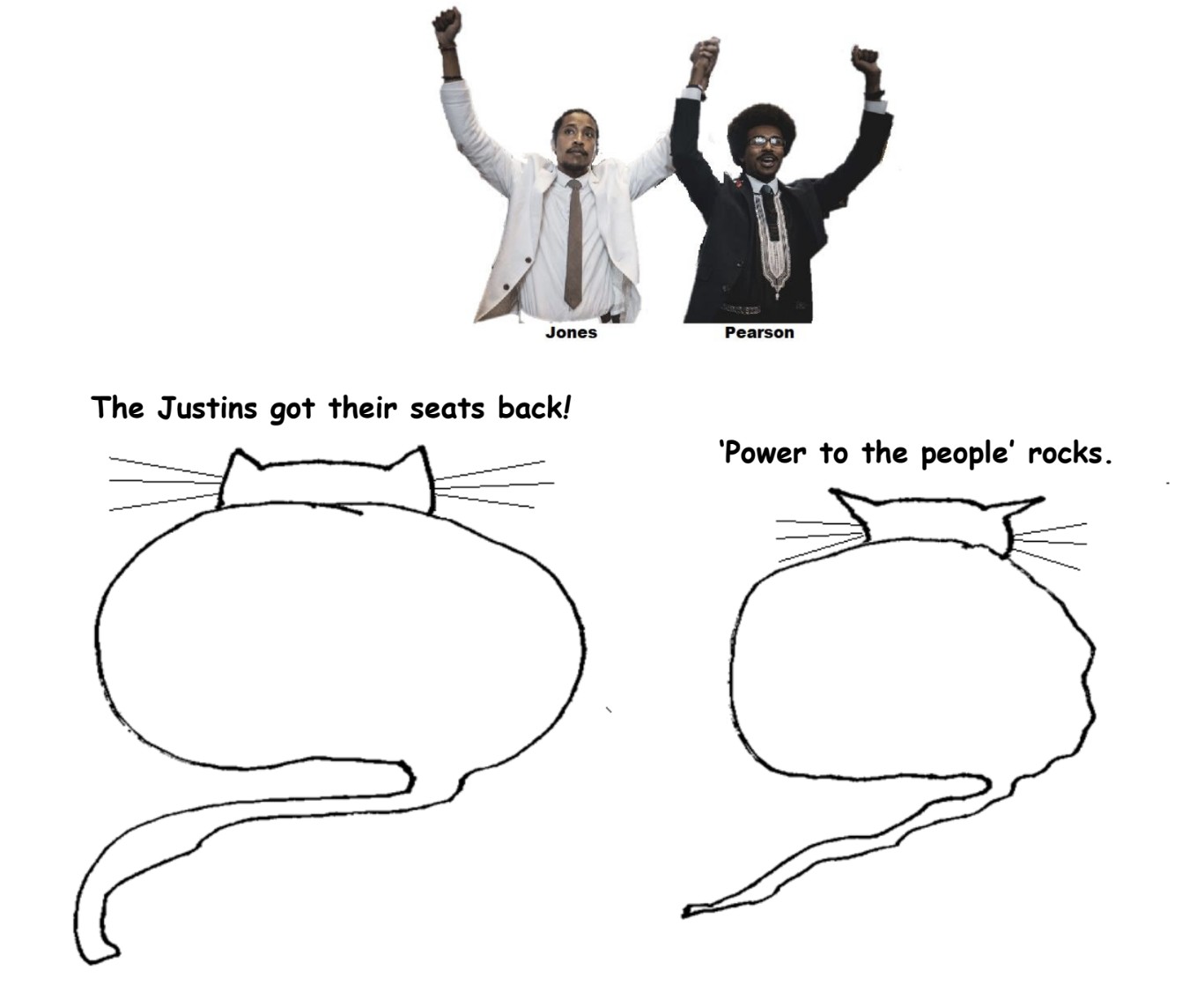

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Hallucinating AI: The devil is in the (computational) details

by Robyn Repko Waller

AI has a proclivity for exaggeration. This hallucination is integral to its success and its danger.

Much digital ink has been spilled and computational resources consumed as of late in the too rapidly advancing capacities of AI.

Large language models like GPT-4 heralded as a welcome shortcut for email, writing, and coding. Worried discussion for the implications for pedagogical assessment — how to codify and detect AI plagiarism. Open-AI image generation to rival celebrated artists and photographers. And what of the convincing deep fakes?

The convenience of using AI to innovate and make efficient our social world and health, from Tiktok to medical diagnosis and treatment. Continued calls, though, for algorithmic fairness in the use of algorithmic decision-making in finance, government, health, security, and hiring.

Newfound friends, therapists, lovers, and enemies of an artificial nature. Both triumphant and terrified exclamations and warnings of sentient, genuinely intelligent AI. Serious widespread calls for a pause in development of these AI systems. And, in reply, reports that such exclamations and calls are overblown: Doesn’t intelligence require experience? Embodiment?

These are fascinating and important matters. Still, I don’t intend to add to the much-warranted shouting. Instead, I want to draw attention to a curious, yet serious, corollary of the use of such AI systems, the emergence of artificial or machine hallucinations. By such hallucinations, folks mean the phenomenon by which AI systems, especially those driven by machine learning, generate factual inaccuracies or create new misleading or irrelevant content. I will focus on one kind of hallucination, the inherent propensity of AI to exaggerate and skew. Read more »

The Great Pretender: AI and the Dark Side of Anthropomorphism

by Brooks Riley

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

That was the voice of the other woman in the car, ‘If possible, please turn around.’ She was nowhere to be seen in the BMW I was riding in sometime in the early aughts, but her voice was pleasant—neutral, polite, finely modulated and real. She was the voice of the navigation system, a precursor of the chatbot—without the chat. You couldn’t talk back to her. All she knew about you was the destination you had typed into the system.

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

She always said this when we missed a turn, or an exit. Since we hadn’t followed her suggestion the first time, she asked us again to turn around. There were reasons not to take her advice. If we were on the autobahn, turning around might be deadly. More often, we just wanted her to find a new route to our destination.

The silence after her second directive seemed excessive—long enough for us to get the impression that she, the ‘voice’, was sulking. In reality, the silence covered the period of time the navigation system needed to calculate a new route. But to ears that were attuned to silent treatments speaking volumes, it was as if Frau GPS was mightily miffed that we hadn’t turned around.

Recent encounters with the Bing chatbot have jogged my memory of that time of relative innocence, when a bot conveyed a message, nothing more. And yet, even that simple computational interaction generated a reflex anthropomorphic response, provoked by the use of language, or in the case of the pregnant silence, the prolonged absence of it. Read more »

Monday Photo

Not Another Lamb

by Eric Bies

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. This is understandable: AI in its current capacity, which we so little understand ourselves, alternately threatens dystopia and promises utopia. We are mostly asking questions. Crucially, we are not asking so much whether the risks outweigh the rewards. That is because the relationship between the first potential and the second is laughably skewed. Most of us are already striving to thrive; whether increasingly superintelligent AI can help us do that is questionable. Whether AI can kill all humans is not.

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. This is understandable: AI in its current capacity, which we so little understand ourselves, alternately threatens dystopia and promises utopia. We are mostly asking questions. Crucially, we are not asking so much whether the risks outweigh the rewards. That is because the relationship between the first potential and the second is laughably skewed. Most of us are already striving to thrive; whether increasingly superintelligent AI can help us do that is questionable. Whether AI can kill all humans is not.

So laymen like me potter about and conceive, no longer of Kant’s end-in-itself, but of some increasingly possible end-to-it-all. No surprise, then, when notions of the parallel and the alternate grow more and more conspicuous in our cultural moment. We long for other science-fictional universes.

Happily, then, did the news of the FDA’s approval of one company’s proprietary blend of “cultured chicken cell material” greet my wonky eyes last month.

“Too much time and money has been poured into the research and development of plant-based meat,” I thought. “It’s time we focused our attention on meat-based meat.”

When I shared this milestone with my students—most of them high school freshmen—opinions were split. Like AI, lab-grown meat was quick to take on the Janus-faced contour of promise and threat. The regulatory thumbs-up to GOOD Meat’s synthetic chicken breast was, for some students, evidence of our steady march, aided by science, into a sustainable future. For other students, it was yet another chromium-plated creepy-crawly, an omen of more bad to come. Read more »

Monday, April 10, 2023

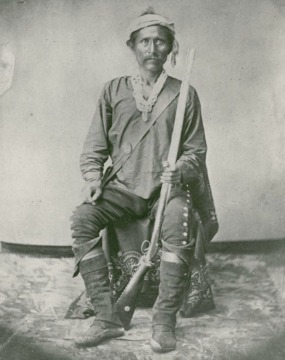

Tribal Waters and The Supreme Court

by Mark Harvey

After we get back to our country, black clouds will rise and there will be plenty of rain. Corn will grow in abundance and everything [will] look happy. –Barboncito, Navajo Leader, 1868

My idea of a fun evening is listening to the oral arguments of a contentious dispute that has reached the Supreme Court. As much as I disagree with some of the justices, I must admit that almost all of them are wickedly sharp at analyzing the issues—the facts and the law—of every case that comes before them. I don’t always get how they arrive at their final votes on cases that seem cut and dried before their probing inquiry. But most of them can flay a poorly presented argument with all the efficiency of a seasoned hunter field-dressing a kill.

So it was with the recent hearing on Arizona v. The Navajo Nation, heard before the court this year on March 20. At stake, in this case, is what responsibility the US government does or doesn’t have in formally assessing the Navajo Nation’s need for water and then developing a plan to meet those needs. The brief on behalf of the Navajo people, Diné as they prefer to be called, puts the case in stark and unmistakable terms: “This case is about this promise of water to this tribe under these treaties, signed after these particular negotiations reflecting this tribe’s understanding. A promise is a promise.”

The promise referred to in the brief refers to a promise made about 150 years ago when the Diné signed a treaty in 1868 with the US Government to establish the Navajo Reservation as a “permanent home” where it sits today. The treaty is only seven pages long and it promises the Diné a permanent home in exchange for giving up their nomadic life, staying within the reservation boundaries, and allowing whites to build railways and forts throughout the reservation as they see fit. A lot of things were left out—like water rights. Read more »

Monday Poem

Trying to make Sense of Red

—A Tennessee Cleanup

Its janitors are sweeping up its sins—

senators are on the floor with whisks and

fine-toothed combs. They crawl and sift,

scooping, collecting photographs

of those they’ve lynched

they cram them into

rubbish bins

—before their kids get wind

they ban their two-faced history,

they ban before their children come to know,

they ban before their jittering pot lid blows

—but

maybe they skew and hack the rules

.. ……… to save kids from what history shows,

maybe they obfuscate for mercy’s sake,

maybe. before their children come to see and judge,

maybe.. .they’d rather have them shot in schools

Jim Culleny, 4/8/23

Are Mass Media and Democracy Compatible?

by Mindy Clegg

In their oft-cited classic examination of the modern mass media, Manufacturing Consent, Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky described modern American news media thusly: “The mass media serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace. It is their function to amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. In a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfill this role requires systematic propaganda.”1 In other words, democratic states use privately-owned media as a means of social control. Private corporations own and operate media outlets and they work with the US government because the power of the state dovetailed with their own economic interests.

The groundwork for this state of affairs emerged out of intellectual discourse in the early days of mass media. In the wake of the first world war, prominent intellectuals like Walter Lippmann and Edward Bernays suggested a set of strategies for channeling democratic impulses expanding in the United States to better align with the wishes of the ruling classes.2 Such analysis was and continues to be necessary, as many are unaware of the very real pitfalls of corporate media in democratic societie. These systems are now often globalized which shape our understanding of the past and present that we must understand in hopes of changing them. But we must also wonder if the singular focus on these systems of control lead to the feelings of hopelessness that many of us feel about our institutions these days. As much as describing what dominates us feels cathartic, focusing only on the systems of control and not on resistance makes the problem seem insurmountable. I argue that we need to look for the cracks as much as describe the problem posed by corporate medi. Understanding the democratic alternatives within and outside of the mainstream production of popular culture can help us to see these cracks. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Digital photograph.

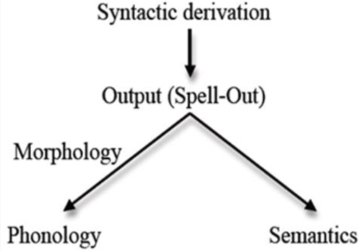

What IS a Natural Language, so that Language Models could learn it (and cognitive scientists stayed sane)?

by David J. Lobina

The hype surrounding Large Language Models remains unbearable when it comes to the study of human cognition, no matter what I write in this Column about the issue – doesn’t everyone read my posts? I certainly do sometimes.

Indeed, this is my fourth, successive post on the topic, having already made the points that Machine/Deep Learning approaches to Artificial Intelligence cannot be smart or sentient, that such approaches are not accounts of cognition anyway, and that when put to the test, LLMs don’t actually behave like human beings at all (where? In order: here, here, and here).[i]

But, again, no matter. Some of the overall coverage on LLMs can certainly be ludicrous (a covenant so that future, sentient computer programs have their rights protected?), and even delirious (let’s treat AI chatbots as we treat people, with radical love?), and this is without considering what some tech charlatans and politicians have said about these models. More to the point here, two recent articles from some cognitive scientists offer quite the bloated view regarding what LLMs can do and contribute to the study of language, and a discussion of where these scholars have gone wrong will, hopefully, make me sleep better at night.

One Pablo Contreras Kallens and two colleagues have it that LLMs constitute an existence proof (their choice of words) that the ability to produce grammatical language can be learned from exposure to data alone, without the need to postulate language-specific processes or even representations, with clear repercussions for cognitive science.[ii]

And one Steven Piantadosi, in a wide-ranging (and widely raging) book chapter, claims that LLMs refute Chomsky’s approach to language, and in toto no less, given that LLMs are bona fide (his choice of words) theories of language; these models have developed sui generis representations of key linguistic structures and dependencies, thereby capturing the basic dynamics of human language and constituting a clear victory for statistical learning in so doing (Contreras Kallens and co. get a tip of the hat here), and in any case Chomskyan accounts of language are not precise or formal enough, cannot be integrated with other fields of cognitive science, have not been empirically tested, and moreover…(oh, piantala).[iii] Read more »