by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

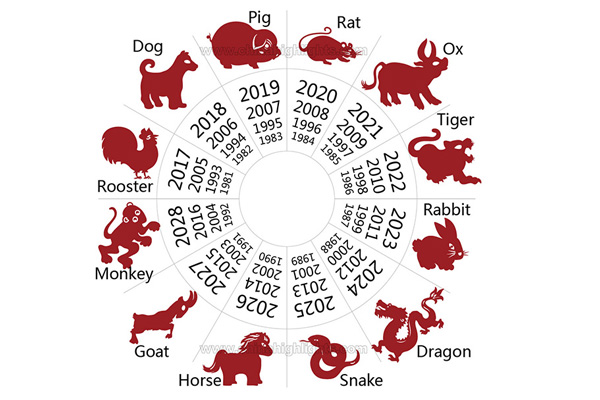

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

Ain’t no rat gonna cut you no slack.

While singing the praises of sheep and trying to hold my own against dragons, snakes and the like, I made a passing reference to the 1977 pop hit “Year of the Cat” by Al Stewart. Didn’t hear the song, didn’t sing it to myself, didn’t even utter the words. Merely wrote Al Stewart’s “Year of the Cat” in a blog post. And that, apparently, is all it took for the song to get stuck in my head.

Why did “Year of the Cat” trap me with such ease? Possibly because it’s one of the very first songs I ever purchased.

The first two long playing, vinyl record I ever bought were a couple of collections called Music Machine and Stars. It was 1979. I was eleven and a half years old. Both albums were put out by a company called K-Tel.

The brainchild of a Winnipeg, Manitoba knife salesman, K-Tel hit it big in the 1960s by taking to the airwaves and hawking various of odds and ends with an intense but simple “As Seen on TV” sales pitch. They started with all sorts of knives and bladed devices like the Veg-O-Matic and the Dial-O-Matic. It slices, it dices, bla bla bla. Other gadgets that wouldn’t make you bleed soon followed. But during the 1970s, the company was best known for music compilations.

It actually began in 1966 with a record called 25 Great Country Artists Singing their Original Hits. That format, a compilation of hit singles by various artists, was still fairly novel, and K-Tel struck gold when combining it with their high octane TV marketing formula. By the time I picked up my two discs, K-Tel had issued over 500 different albums, mostly collections. Read more »