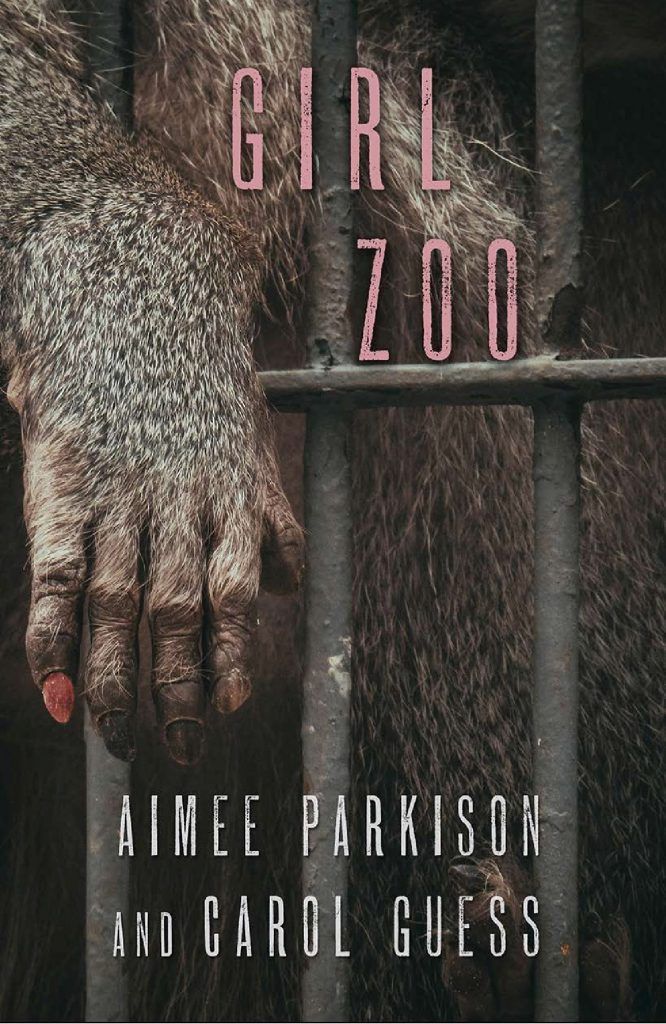

Andrea Scrima: Girl Zoo, which has just been published by the FC2 imprint of the University of Alabama Press, is a collection of stories that takes contemporary feminist theory on an odyssey through the collective capitalist subconscious. Scenes of female incarceration are nightmarish, hallucinatory: each story exists within its own universe and operates according to its own set of natural laws. But while there’s a fairy-tale quality to the telling, none of these stories departs very far from the everyday experience of institutionalized sexism: the all-too-familiar is magnified just enough to reveal its inherently devastating proportions.

Aimee, Carol, I wonder if we could begin by talking about the collaborative process. How did the idea come about to write a book together?

Aimee Parkison: As an artist, I’m always trying new things. I have a wide range and want to expand and explore. My creative process is vital to the way I experience the world. I like the excitement of a new project, a new idea. I write all sorts of stories, from flash fictions to long narratives, from experimental to traditional, from realism to surrealism. Some of my fictions are character-based and others more conceptual. I often focus on the lives of women and am known for revisionist approaches to narrative and poetic language. My writing is often categorized as experimental or innovative. I’ve published five books of fiction, story collections, and a short novel. I’ve been published widely in literary journals. Among my previous books are Refrigerated Music for a Gleaming Woman (FC2 Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize) and a short novel, The Petals of Your Eyes (Starcherone/Dzanc). I admire Carol’s writing and had interviewed her for a couple of articles I was writing for AWP’s The Writer’s Chronicle magazine. A year or so after the interview, she emailed me, inviting me to do a collaboration.

Carol Guess: My approach to writing came through music and dance. Years ago, I studied ballet and moved to New York to try to make a career in that world. Obviously that didn’t happen, but my early experience with failure made me determined to be good at something else! I’d always written for pleasure, so I began taking my writing more seriously, initially focusing on poetry. I did my MFA in poetry; I’ve never actually taken a class in fiction writing. I put my first novel together as an experiment. I wanted to teach myself how to write a novel, and so I did. Since then I’ve published twenty books, each one an experiment and a challenge. I’ll ask myself, “What would happen if …” and then set out to answer my own question. Read more »

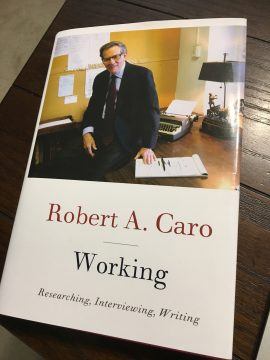

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.