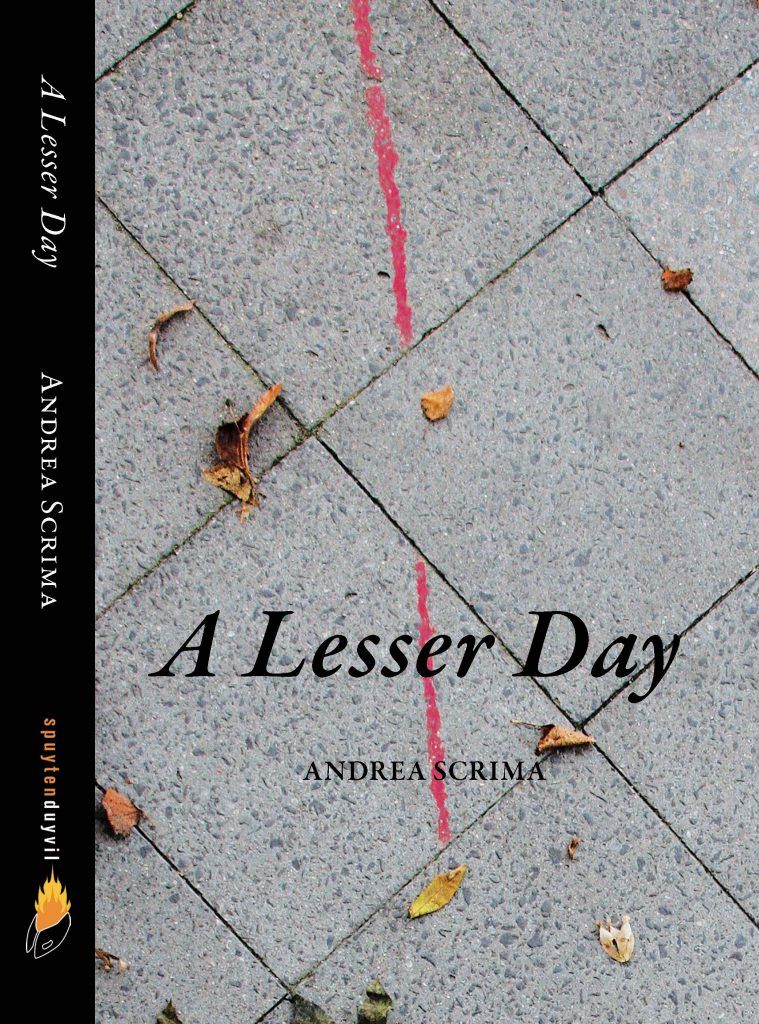

Andrea Scrima’s “The Ethnic Chinese Millionaire” at Manière Noire consists of a two-part, large-scale text installation, a small sculpture, and a news photo printed on the invitation card. These three elements interlock in an intricate manner, while the exhibition stands in relation to the novel A Lesser Day, which has recently come out in German translation [Wie viele Tage, Literaturverlag Droschl, 2018]. I spoke to the artist and author about the connections between literature and art, image and reproduction, description of image and text turned into space—in other words, about the multimodal signification processes of this complex work. The following conversation took place via email over a period of several weeks for the most part in August and September, 2018. –Myriam Naumann

Myriam Naumann: “Kent Avenue; how I hadn’t done anything I’d set out to do in New York, how I’d called off the exhibition and worked on the book instead…” In A Lesser Day, processes of emergence and coalescing, for instance of perception or materiality, are always present. At one point, the actual writing of a book becomes the subject matter of the text. How did A Lesser Day and its German translation come about?

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text? Read more »

Andrea Scrima: As a visual artist, I worked in the area of text installation for many years, in other words, I filled entire rooms with lines of text that carried across walls and corners and wrapped around windows and doors. In the beginning, for the exhibitions Through the Bullethole (Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha), I walk along a narrow path (American Academy in Rome) and it’s as though, you see, it’s as though I no longer knew… (Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin in cooperation with the Galerie Mittelstrasse, Potsdam), I painted the letters by hand, not in the form of handwriting, but in Times Italic. Over time, as the texts grew longer and the setup periods shorter, I began using adhesive letters, for instance at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Kunsthaus Dresden, the museumsakademie berlin, and the Museum für Neue Kunst Freiburg. Many of the texts were site-specific, that is, written for existing spaces, and often in conjunction with objects or photographs. Sometimes it was important that a certain sentence end at a light switch on a wall, that the knob itself concluded the sentence, like a kind of period. I was interested in the architecture of a space and in choreographing the viewer’s movements within it: what happens when a wall of text is too long and the letters too pale to read the entire text block from the distance it would require to encompass it as a whole—what if the viewer had to stride up and down the wall? And if this back and forth, this pacing found its thematic equivalent in the text? Read more »