by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Most are already familiar with many of the thoughts driving the Ancient Paradoxical ethical tradition. Surely we’ve all either thought and endorsed or at least heard someone express thoughts along the following lines:

Most are already familiar with many of the thoughts driving the Ancient Paradoxical ethical tradition. Surely we’ve all either thought and endorsed or at least heard someone express thoughts along the following lines:

It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game.

It’s not getting what you want, it’s wanting what you get.

Being good is its own reward.

Let’s first note an important terminological point about the paradoxical tradition. Paradox is a Greek word that, in its classical usage, that meant something counter intuitive, something surprising. Para, meaning alongside or against, and doxa, belief. So a paradox is something that runs against what we normally believe. In short, those who belong to the paradoxical tradition say surprising things. Now, the paradox is most clearly in view for us, as we endorse sentiments like It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s how you play the game, but we nevertheless cheer for winners, and nobody makes it to any Halls of Fame simply for being a good sport. The same goes for all the familiar old saws – we think they are right, but nevertheless don’t live in accord with them. The paradoxical tradition is one of consistently living in accord with sentiments like these.

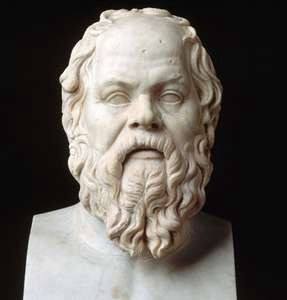

Socrates was one of the first great paradoxicalists, and one of the most famous. One particular paradox he announces after the Athenians sentence him to death for impiety and corrupting the young. He says he does not believe “a good man can be harmed in life or in death” (Apology 41d). And so we have the first of the ancient paradoxes of the good life, call it:

The paradox of invulnerability: Insofar as you are virtuous, you cannot be truly harmed.

Now what makes this view paradoxical is that Socrates says this in the face of a jury who’ve sentenced him to death. Having to drink hemlock and suffer its effects. That sounds like a harm. Dying? It certainly seems worse than living on and being Socrates. How else might someone consider it a punishment?

The paradoxical perspective on this is that these slings and arrows of outrageous fortune would be harms only if they harmed our souls. A death sentence is a harm only if it makes you willing to grovel, lie and cheat to avoid it. Poverty and suffering are harms only if it makes you a horrible person, violent, or selfish. Illness is a harm only if it makes you resentful and empty.

The world can destroy us, but if we live well, it cannot destroy the good in us. The world can take the light of goodness inside you only if you let it. Our job is to tend and care for that light of decency and goodness inside us. Virtue ensures it’s not snuffed out.

Read more »

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

Socrates, snub-nosed, wall-eyed, paunchy, squat,

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.