by Fabio Tollon

Getting a handle on the various ways that technology influences us is as important as it is difficult. The media is awash with claims of how this or that technology will either save us or doom us. And in some cases, it does seem as though we have a concrete grasp on the various costs and benefits that a technology provides. We know that CO2 emissions from large-scale animal agriculture are very damaging for the environment, notwithstanding the increases in food production we have seen over the years. However, such a ‘balanced’ perspective usually emerges after some time has passed and the technology has become ‘stable’, in the sense that its uses and effects are relatively well understood. We now understand, better than we did in the 1920s, for example, the disastrous effects of fossil fuels and CO2 emissions. We can see that the technology at some point provided a benefit, but that now the costs outweigh those benefits. For emerging technologies, however, such a ‘cost-benefit’ approach might not be possible in practice.

Take a simple example: imagine a private company is accused of polluting a river due to chemical runoff from a new machine they have installed (unfortunately this probably does not require much imagination and can be achieved by looking outside, depending on where you live). In order to determine whether the company is guilty or not we would investigate the effects of their activities. We could take water samples from the river and attempt to show that the chemicals used in the company’s manufacturing process are indeed present in the water. Further, we could make an argument where we show how there is a causal relationship between the presence of these chemicals and certain detrimental effects that might be observed in the area, such as loss of biodiversity, the pollution of drinking water, or an increase in diseases associated with the chemical in question. Read more »

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Among the ideas in the history of philosophy most worthy of an eye-roll is Aristotle’s claim that the study of metaphysics is the highest form of eudaimonia (variously translated as “happiness” or “flourishing”) of which human beings are capable. The metaphysician is allegedly happier than even the philosopher who makes a well-lived life the sole focus of inquiry. “Arrogant,” self-serving,” and “implausible” come immediately to mind as a first response to the argument. It’s not at all obvious that philosophers, let alone metaphysicians, are happier than anyone else nor is it obvious why the investigation of metaphysical matters is more joyful or conducive to flourishing than the investigation of other subjects.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the  For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like.

For many wine lovers, understanding wine is hard work. We study maps of wine regions and their climates, learn about grape varietals and their characteristics, and delve into various techniques for making wine, trying to understand their influence on the final product. Then we learn a complex but arcane vocabulary for describing what we’re tasting and go to the trouble of decanting, choosing the right glass, and organizing a tasting procedure, all before getting down to the business of tasting. This business of tasting is also difficult. We sip, swish, and spit trying to extract every nuance of the wine and then puzzle over the whys and wherefores, all while comparing what we drink to other similar wines. Some of us even take copious notes to help us remember, for future reference, what this tasting experience was like. One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

One problem plaguing contemporary anti-Cartesians (pragmatists, Wittgensteinians, hermeneutic philosophers, etc.) is that it can seem that we are competing against each other, trying to do better than everyone else what we all want to do: get past the dualisms and other infelicities of the modern picture while at the same time absorbing its lessons and retaining its good aspects. We waste our time fighting each other instead of our common enemy. Why is it so hard to see ourselves as all on the same team?

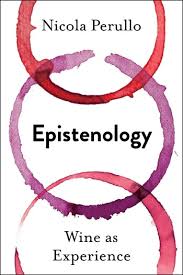

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Epistenology: Wine as Experience

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.

Philosophy has been an ongoing enterprise for at least 2500 years in what we now call the West and has even more ancient roots in Asia. But until the mid-2000’s you would never have encountered something called “the philosophy of wine.” Over the past 15 years there have been several monographs and a few anthologies devoted to the topic, although it is hardly a central topic in philosophy. About such a discourse, one might legitimately ask why philosophers should be discussing wine at all, and why anyone interested in wine should pay heed to what philosophers have to say.