by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Ami, my mother, does my hair, “Helen-of-Troy-style,” a high pony tail with strands wrapped around it on days there is extra time before school. She remembers the hairdo from an old movie which she talks about often, along with her other favorite The Taming of the Shrew with Liz Taylor. When she combs, she hums, mostly Urdu songs, occasionally Punjabi. Since settling in Peshawar, she has taught herself Pashto not only because it isn’t easy to run a household and her myriad projects without knowing the local language, but because she has a genuine love for connecting with people of all kinds, everywhere. We joke that she can make friends while crossing the road; this is something she and I don’t have in common. I tend to be withdrawn, like my father, content with my books and thoughts.

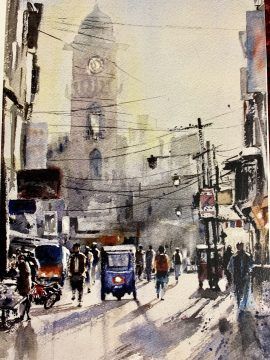

There are times when I do enjoy going on outings, especially when Ami takes me on an excursion to the old city and shows me how herbs, spices, henna, tealeaves, and grains of every kind are sold box-less, displayed in smooth mounds. I like to walk through the narrow streets with her, taking in the crisp, salty aroma of street food, the colors of sherbets, glass bangles, sparkly trim for dupattas, watching shopkeepers with their paraphernalia— their weighing scales, aluminum scoops and glossy brown paper bags. The joy of walking through a bazar, which will become a subject I’ll explore for years in my writing, begins here. I feel certain that if I were to put my ear to the ground, I’ll hear the tread of Silk Road caravans. My curiosity about how cultures of encounter are formed and revealed in the marketplace— about trade- and work habits, competition and conflict, creative marketing, the ethos of fair-play and equality and the complex dynamics of cosmopolitanism— is born as a result of watching my mother interact. I’m astonished by how she varies the language or dialect, accent or register, “code-switching” naturally as she goes. Read more »