by Barbara Fischkin

Moving forward, I plan to use this space to experiment with chapters of a memoir. Please join me on this journey. Another potential title: “Barbara in Free-Range.” I realize this might be stepping on the toes of Lenore Skenazy, the celebrated former New York News columnist, although I don’t think she’d mind. Lenore was also born a Fishkin, albeit without a “c” but close enough. We share a birthday and the same sensibilities about childhood. These days Lenore uses the phrase “free-range,” typically applied to eggs, to fight for the rights of children to explore on their own as opposed to being over-supervised and scheduled.

I feel free-range, myself. I don’t like rules, particularly the unnecessary and ridiculous ones. My friend Dena Bunis, who recently died suddenly and too soon, once got a ticket for jaywalking on a traffic-free bucolic street in Orange County, California. She never got a jaywalking ticket in other far more congested places like New York City and Washington, D.C.

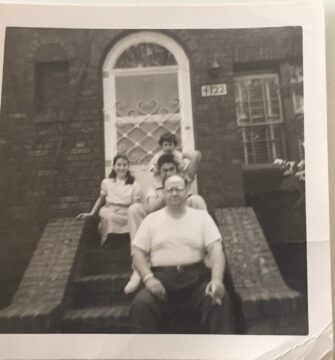

As a kid, I was often free-range, thanks to my parents, old timers blessed with substantial optimism. I have been a free-range adult. I was a relatively well-behaved teen but did not become a schoolteacher as recommended as a good job for a future wife and mother. I wanted a riskier existence as a newspaper reporter. I did not marry the doctor or lawyer envisioned as the perfect husband for me by ancillary relatives and a couple of rabbis. Instead, I married Jim Mulvaney, now my Irish Catholic spouse of almost forty years, because I knew he would lead, join or follow me into adventures.

I left newspapering as my career was blooming to write books, none of which made me a literary icon or even a little famous. I am glad I wrote them. Read more »