by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

I am no stranger to waking up in the middle of the night with a nameless feeling of dread. Like everyone else I know, I developed chronic insomnia around age 40, which was exacerbated by the “election” of Trump and the ongoing pillage of American democracy. And then perimenopause wreaked its havoc in the form of hormonal swings, night sweats, and troubled dreams. But this was different. This night—just over a month ago—I woke bolt upright out of a dead sleep, gasping for air, disoriented and terrified. I leapt out of bed and staggered to the bathroom, so dizzy I was bumping into walls. I found the toilet, closed the lid (an ongoing bone of contention in our household), and sank down with my head between my knees. I was dying. I knew, absolutely and with pure and stainless conviction, that I was dying. Dizziness washed over me, an intense feeling of disorientation, and I knew that it was my spirit separating from my body. I was swept with waves of grief. I haven’t written everything I want to write. My partner is in the next room and I don’t want to say goodbye yet. My family, my friends. Work to do, parties to throw. This toilet—it really needs to be cleaned. This is not dignified. I promise, Powers That Be, that from this moment forward I will no longer be cavalier about my life, if you just spare me now.

Suddenly a scrap of memory. A conviction that one is dying—that sounds familiar. I think … that can happen in panic attacks? Maybe I’m having a panic attack? But—how can this be? I have had panic disorder and intermittent generalized anxiety since I was 16, and have had hundreds of panic attacks in my life—never before did I become convinced that I was dying. For me the worst part of panic is the feeling of derealization, as if the world around me is fake and I am in a dream. (It’s very difficult to explain why this feeling is so horrifying to those who have never experienced it—you just have to trust me.) But that night in the bathroom I suddenly remembered that the sensation of dying is on the long list of panic attack symptoms, one I had always skipped over when reading about my disorder since it didn’t apply to me. And yet here we were.

Okay, okay. I might as well try the usual techniques I’ve perfected over the years. Deep breathing. Walking in circles while shaking my hands and feet. Splashing cold water on my face. Above all—not fighting it. Letting the feelings pass through me and trusting that I would come out the other side. It worked; I was released from the iron grip of terror; my soul returned to my body; I lived.

I did not sleep again that night. Read more »

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s

Barring that reality, and knowing this would be an ongoing, lifelong issue, I got a tattoo on my Visa-paying forearm to remind myself that my actions affect the entire world. I borrowed Matisse’s  A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s

A dear friend of mine recently passed away unexpectedly. He had recommended I read Viktor Frankl’s  The season finale of

The season finale of  This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

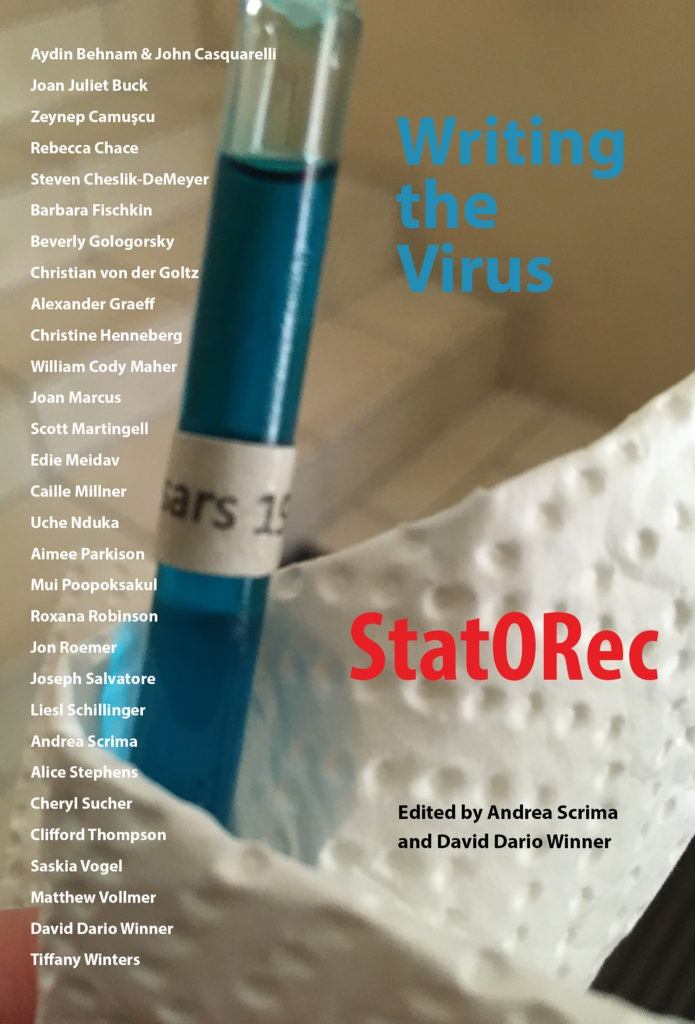

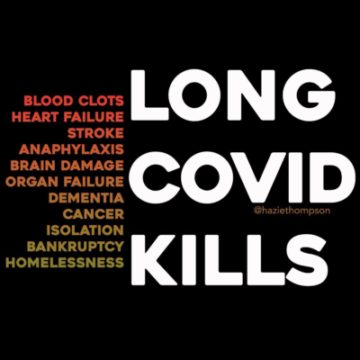

This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band. Two profound horrors have plagued the world in recent times: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency. And after years of dread, their recent decline has brought me a brief respite of peace.

Two profound horrors have plagued the world in recent times: the Covid-19 pandemic and the Trump presidency. And after years of dread, their recent decline has brought me a brief respite of peace.