by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met here. I ask you to support artists wherever and however you can.

Peter de Swart, works on paper: Triptych

The triptych form is associated with religious painting. It first appeared as a feature of early Christian art and became popular for altar paintings and devotionals during the Middle Ages. While Peter de Swart’s Triptych is not overtly religious, it emanates an undeniably religious or spiritual aura. It is, in a word, numinous. To encounter this painting is to witness a sacred transaction. You’d have to be a stone to look at it and not experience a yearning for the divine. Why, apart from its rearticulation of the history and symbolism of the triptych form, is that?

It must have something to do, first of all, with the simple purity of the object pictured, which appears to be a bowl of some sort. Bowls are one of those inventions (like scissors or chopsticks or the hourglass) that we got right the first time. They were perfect the moment they appeared. In the bowl, function lives harmoniously with form. Its shape is so ideal as to be almost Platonic. Furthermore, bowls are used to prepare and serve food and drink, which means that they give sustenance, enable shared meals, and consequently help to strengthen communal bonds and deepen human relationships. Finally, bowls are vessels. Like hands and pockets and ships, they hold and contain and convey things—but they are not grasping like hands, nor like pockets do they secret away their contents, and they don’t trade goods and gold like ships. Quite the opposite, in fact: Bowls are generous, open, gratuitous. They give away the things they hold.

All of these attributes (form, use value, ethos) lend bowls a quasi-spiritual redolence, but they do not make bowls sacred. If this triptych depicted a bowl no different from any other bowl, then its effect would be decorative rather than numinous. This bowl is special. Again we must ask: Why is that? Read more »

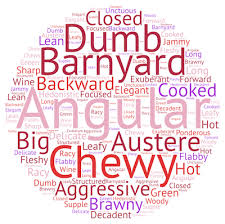

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative. Research by linguists

Research by linguists The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even

The wine community is often accused of being snobby and elitist. The language used to describe wine is one source of this innuendo. Although most people have become accustomed to the fruit descriptors used in wine reviews, when wine writers wax poetic by describing wines as “graphite mixed with pâte de fruit”, even  Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists  Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make.

Wine is a living, dynamically changing, energetic organism. Although it doesn’t quite satisfy strict biological criteria for life, wine exhibits constant, unpredictable variation. It has a developmental trajectory of its own that resists human intentions and an internal structure that facilitates exchange with the external environment thus maintaining a process similar to homeostasis. Organisms are disposed to respond to changes in the environment in ways that do not threaten their integrity. Winemakers build this capacity for vitality in the wines they make. Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.

Among the best books I’ve read about wine are the two by wine importer Terry Theise.  It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation. Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful.

Why do we value successful art works, symphonies, and good bottles of wine? One answer is that they give us an experience that lesser works or merely useful objects cannot provide—an aesthetic experience. But how does an aesthetic experience differ from an ordinary experience? This is one of the central questions in philosophical aesthetics but one that has resisted a clear answer. Although we are all familiar with paradigm cases of aesthetic experience—being overwhelmed by beauty, music that thrills, waves of delight provoked by dialogue in a play, a wine that inspires awe—attempts to precisely define “aesthetic experience” by showing what all such experiences have in common have been less than successful. If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry?

If a rectangular canvas splashed with paint and lines can express freedom or joy, why not liquid poetry? In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame.

In giving an account of the aesthetic value of wine, the most important factor to keep in mind is that wine is an everyday affair. It is consumed by people in the course of their daily lives, and wine’s peculiar value and allure is that it infuses everyday life with an aura of mystery and consummate beauty. Wine is a “useless” passion that has a mysterious ability to gather people and create community. It serves no other purpose than to command us to slow down, take time, focus on the moment, and recognize that some things in life have intrinsic value. But it does so in situ where we live and play. Wine transforms the commonplace, providing a glimpse of the sacred in the profane. Wine’s appeal must be understood within that frame. Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past. The wine world thrives on variation. Wine grapes are notoriously sensitive to differences in climate, weather and soil. If care is taken to plant grapes in the right locations and preserve those differences, each region, each vintage, and indeed each vineyard can produce differences that wine lovers crave. If the thousands of bottles on wine shop shelves all taste the same, there is no justification for the vast number of brands and their price differentials. Yet the modern wine world is built on processes that can dampen variation and increase homogeneity. If these processes were to gain power and prominence the culture of wine would be under threat. The wine world is a battleground in which forces that promote homogeneity compete with forces that encourage variation with the aesthetics of wine as the stakes. In order to understand the nature of the threat homogeneity poses to the wine world and the reasons why thus far we’ve avoided the worst consequences of that threat we need to understand these forces. I will be telling this story from the perspective of the U.S. although the themes will resonate within wine regions throughout much of the world.

The wine world thrives on variation. Wine grapes are notoriously sensitive to differences in climate, weather and soil. If care is taken to plant grapes in the right locations and preserve those differences, each region, each vintage, and indeed each vineyard can produce differences that wine lovers crave. If the thousands of bottles on wine shop shelves all taste the same, there is no justification for the vast number of brands and their price differentials. Yet the modern wine world is built on processes that can dampen variation and increase homogeneity. If these processes were to gain power and prominence the culture of wine would be under threat. The wine world is a battleground in which forces that promote homogeneity compete with forces that encourage variation with the aesthetics of wine as the stakes. In order to understand the nature of the threat homogeneity poses to the wine world and the reasons why thus far we’ve avoided the worst consequences of that threat we need to understand these forces. I will be telling this story from the perspective of the U.S. although the themes will resonate within wine regions throughout much of the world. It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month

It is fashionable to say that great wine is made in the vineyard. There is a lot of truth to that slogan but in fact wine is made by a complex assemblage with various factors influencing the final product. Last month  The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As

The wine world is an interesting amalgam of stability and variation. As  Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time. From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.

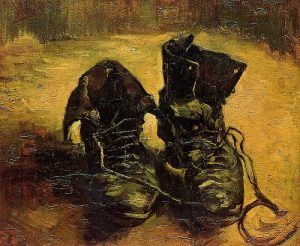

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love. Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.  Although wine writing takes diverse forms, wine evaluation is a persistent theme of much wine writing. When particular wines, wineries or vintages are under discussion, at some point the writer will typically turn to assessing wine quality. The major publications devoted to wine include tasting notes that not only describe a wine but indicate its quality, often with the help of a numerical score, and most wine blogs and online wine magazines include a wine evaluation component that is central to their mission.

Although wine writing takes diverse forms, wine evaluation is a persistent theme of much wine writing. When particular wines, wineries or vintages are under discussion, at some point the writer will typically turn to assessing wine quality. The major publications devoted to wine include tasting notes that not only describe a wine but indicate its quality, often with the help of a numerical score, and most wine blogs and online wine magazines include a wine evaluation component that is central to their mission. Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?

Although frequently lampooned as over-the-top, there is a history of describing wines as if they expressed personality traits or emotions, despite the fact that wine is not a psychological agent and could not literally have these characteristics—wines are described as aggressive, sensual, fierce, languorous, angry, dignified, brooding, joyful, bombastic, tense or calm, etc. Is there a foundation to these descriptions or are they just arbitrary flights of fancy?