At close to 71 million votes, Donald Trump beat Barack Obama’s 2008 total of 69.5 million, which had been the highest number of votes ever cast for a presidential candidate (Wikipedia). But Joseph Biden got over 75 million votes to win. Those numbers alone make this a landmark election.

The nature of the opposition, the candidates, the voters, the issues, the general state of the nation, that too is important. But I don’t know how to  think about that. Though others may have one, I lack an analytic framework. The best I can do is to offer some things I’ve been thinking about.

think about that. Though others may have one, I lack an analytic framework. The best I can do is to offer some things I’ve been thinking about.

Be of Good Cheer

Let us start with Episode 223 of the In Lieu of Fun podcast, or whatever it is, from the day after, Nov. 4. It is hosted by Ben Wittes, of the Brookings Institution and Lawfare, and Kate Klonick, who teaches at St. Johns University School of Law. They’ve been hosting this conversation since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the whole conversation is worthwhile, especially some relatively early remarks taking note of the fact that Trump still has a great deal of support, I’m interested in some remarks that Wittes offered at the very end, starting at roughly 55:49 (you have to view it on Youtube).

It really really matters who’s President. And so if Joe Biden does nothing more than stop the craziness, he will be in the top few percentiles of Presidents in the history of the country. If all he does is rebuild the executive branch in a sane fashion.

Can he work with Mitch McConnell? I don’t know. Will they work together on the things that have to get done? Yes, because they’re both pros. Don’t underestimate that. Mitch Connell is a nasty fellow, but he’s a professional. I just what to say, it matters who’s President. What Donald Trump has shown is in a negative sense how much a President can do. All of that can be undone. … At the end of the day, this country is in much better shape today than it was 24 hours ago. … Be optimistic, be of good cheer.

Think about that for a minute. Forget about what legislation a Biden administration might effect, forget about “packing” the Supreme Court. Think only about restoring order to the executive branch. THAT that can possibly count as a major achievement implies that four more years of Trump would have imperiled our basic mode of governance.

Is that so? And if so, can it be rescued merely by restoring the executive branch?

I note that The American Prospect has a list of 277 policies Biden can enact without congressional approval.

A World of Coal and Steel

I spent most of my childhood in Western Pennsylvania in Johnstown, PA, which had a peak population of 67 thousand early in the 20th century, declining to 50-60 thousand when I lived there – though I didn’t live in the city proper, but in a suburb, and now just over 19 thousand. At the time of the Civil War Johnstown’s Cambria Iron Works produced more steel than any other plant in the nation. When I lived there those works had long been incorporated into the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, which was the second largest steel company in the nation. United States Steel, the largest steel company, had a smaller plant in Johnstown as well. The Bethlehem Steel Corporation finally went bankrupt in 2001 and its remaining assets were finally sold in 2003. U.S. Steel remains.

My father worked for Bethlehem Mines, a subsidiary, which provided iron ore and coal for the manufacture of steel. My father had technical responsibility for the design and operation of the plants that cleaned coal of impurities, mostly sulfur-bearing rock, so it could be used in smelting iron ore. He took frequent trips to West Virginia and Kentucky, where the coal was mined.

We also had coal in our house, which was heated by a coal-fired furnace. In the late fall a truck would back into our driveway and dump a load of coal into the basement. I forget the exact mechanical arrangements, but there was a small chute that lead into the coal bin, a small room in a corner of the basement. We probably had a wheel barrow to help move the coal from the bin over next to the furnace; it wasn’t far, but carrying shovelfuls of coal ten feet or so would have been awkward. At some point that furnace was replaced by an oil-burner and an oil tank went into the coal bin.

Sixteen Tons and Deeper in Debt

The song, “Sixteen Tons” was written in 1946 by Merle Travis and came out of the Kentucky coal mines.

I remember it from the mid-1950s when the version by Tennessee Ernie Ford topped the charts. And when I say “remember” I mean that I can readily conjure it up in my mind’s ear.

Here’s the refrain:

You load sixteen tons and what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

Saint Peter don’t you call me, ‘cause I can’t go.

I owe my soul to the company store.

The Library of Congress included it in the National Recording Registry in 2015.

For what it’s worth, my father believed the no one who hadn’t first worked in a coal mine should be entrusted with management responsibility for a mine.

A good Democrat bag

I remember one Halloween when my bag of candy was beginning to fall apart and I was not yet home. Perhaps it was a presidential election year – 1956, 1960? – because the man who met us at the door asked my political affiliation. To be sure, I don’t remember exactly what he asked and I was way too young to vote, but somehow I offered “Republican” and he gave me a “good Democrat” bag to replace my fraying Republican bag. I believe that was Mr. Cannone (?); I was friends with his son, Nick; they owned a roadhouse.

I also have vague memories of newspaper headlines about a steel strike, seeing stories in the TV news, hearing conversations about it. Trade unions were important then, with the United Steel Workers and United Mine Workers being particularly important to Johnstown. Then of course we had the United Auto Workers and the Teamsters. It is certainly a gross exaggeration to say that the movies about the murder of Teamster president Jimmy Hoffa are about all that’s left of the union movement.

I will point out however that, while Joe Biden carried California easily, the state also passed a proposition (22) that defined app-based drivers as contractors rather than as employees. Those unions, and others, still exist, though in somewhat different form and constitution than they had at mid-century. But labor isn’t the political force that it once was. This gig economy is looking more and more like a disaster for the gigged.

Johnstown Votes for Trump

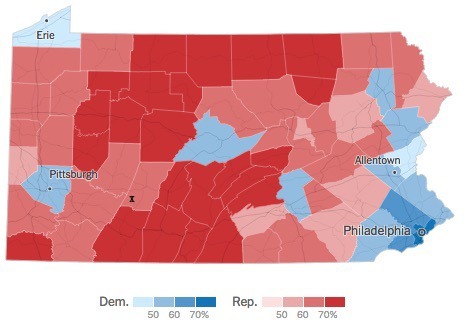

Donald Trump, the wealthy son of a wealthy New York City real estate developer and owner, has somehow managed to step into the void left by the decline of industrial America. I don’t know the voting history of Cambria County, where Johnstown is located, but in this election 68% of the county’s votes went to Donald Trump. Here’s the New York Times voting map of Pennsylvania:

The blue counties went to Democrats, the red to the GOP. Johnstown, marked with an X, is in Trump territory.

Obama Voters Who Flipped for Trump

Glen Loury is an economist at Brown University and has been hoasting The Glen Show for over a decade. He recently had a discussion with John Shields, co-author, with Stephanie Muravchik, of Trump’s Democrats, Brookings Institute Press, 2020. They undertook ethnographic studies of three places that flipped for Trump in 2016. Ottumwa, Iowa, has voted Democratic since 1972 and is centered on a meatpacking plant. Johnston, Rhode Island, last voted Republican in 1984 and is a suburb of Providence, RI. Elliott County, Kentucky, never voted Republican before 2016; the economy is based on coal and tobacco.

I recommend the whole conversation, but if you want to economize, start with the material on honor culture starting at about 19:16 and continue on.

The publisher’s blub for the book indicates some of the themes from the conversation:

In these communities, some of the most beloved and longest-serving Democratic leaders are themselves Trumpian—grandiose, combative, thin-skinned, nepotistic. Indifferent to ideology, they promise to take care of “their people” by cutting deals—and corners if needed. Stressing loyalty, they often turn to family to fill critical political roles. Trump strikes a familiar figure to these communities, resembling an old-style Democratic boss.

Although Trump’s Democrats have often been pictured as racists, Muravchik and Shields find that their primary political allegiances are to their town or county—not racial identity. They will spend an extra dollar to patronize local businesses, and they think local jobs should go to their neighbors, not “foreigners” from neighboring counties—who are just as likely to be white and native-born.

When these citizens turn their attention to the nation and their place in it, their thinking is informed by their sense of belonging in their town. Thus, “America first” nationalism is largely localism writ large.

Keep that last paragraph in mind as you read the next and final section.

It’s happening all over

One thread of thought that keeps appearing over and over is that, whatever it is that’s happening in the United States, is happening all over. Here are some some observations that Tim Burke, a historian at Swarthmore (in eastern Pennsylvania outside of Philadelphia), made on the day after the election:

… people in deindustrialized cities, materially decomposing suburbs, in lower-managerial positions bossed or owned by pedigreed professionals, running small businesses that depend on the culturally protean consuming largesse of educated elites, in rural communities that produce food and boredom in equal measure, have some coherently connected reasons to resent their situation. And hence, even if they are not a clear majority of the inhabitants of a given national territory, are often able to mobilize a political response that either lets them capture the nation-state or lets them block the political will of the much more socially and ideologically fractured opposing alliance. And this reaction has no devotion to democracy, equality or liberalism. It will, if it seizes any system or structure that allows the use of violence and domination, gladly deploy them with little concern even for collateral damage to its own social redoubts.

Scholars have known for a long time that nations and nationalism are much less distinct from empires than it might seem. To some extent, they are empires that performed a level of political and cultural integration in the 19th and 20th Centuries that concealed their remaining, continuously reproduced forms of territorial difference and divergence. Western intellectuals in the late 20th Century liked to talk high-handedly of postcolonial states as divided by ethnic or religious rivalries that were a result of badly constructed boundaries drawn by colonial rulers and uncorrected by postcolonial inheritors. But I think now we are seeing those nation-states were not a defective variant of the main form: we are seeing that everywhere the nation is not what it seems and nowhere does loyalty to the nation create a fellowship that transcends other forms of territorial, economic and cultural affinity and alliance. And contrary to some of the sentimental weepiness in American public life this morning, it never really did. This is not a world we have lost, it is an illusion that has been popped like the soap bubble it has always been.

It’s this last observation that I find most problematic and troublesome, for I fear it is true. It suggests that we here in the United States are facing more than a strenuous challenge to our particular institutions. Rather we are facing the world-wide collapse of a form of governance, the nation-state. If so, then we cannot fix is be rearranging the various coalitions in our political ecology and perhaps adding an amendment or three to the Constitution. We may have to imagine and implement a new form of governance.

What does that even mean?