by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

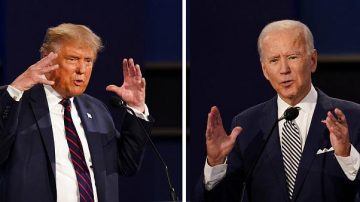

The first of the US Presidential debates between incumbent Donald Trump and challenger Joe Biden is complete, and from the looks of the political landscape after Trump’s positive COVID test, it may be the only debate for this election cycle. Most who watched the debate called it a ‘food fight,’ a ‘brawl,’ or worse. Trump interrupted Biden, there was too much crosstalk, there were insults, and Biden even told the President to “Shut up, man!” Anyone who tuned in to see two candidates for America’s highest office exchange well-reasoned arguments, hold each other accountable to challenge, and answer each other’s questions was sorely disappointed.

But the reality is that debates never have been that idealized exchange. For sure, many debates have better resembled it than this more recent one, but no debates have been close to that aspirational posit. Rather, the debates are more simultaneous campaign events, where the candidates can recite clips of their stump speeches, drop practiced one-liners, and play at having rapport with the moderator when being held to the rules of the debate. What makes them important in this argumentative regard, then, is how well they enact their brand within the rules of the forum. It’s along these lines that we think that Trump is right that he won the debate.

Biden’s brand is that he is the moderate who can beat Trump. Trump’s brand is that he is the powerful disruptor, the one who is so strong that no rules can constrain him. Seen from this perspective, the debate was wholly a case of Trump’s singular dominance. He, again, interrupted Biden, he derailed Biden’s argument about his disparagement of the military with a shot about Biden’s younger son, he squabbled with the moderator about whether the rules were right, and he consistently went over his allotted times. He indeed was a disruptor, one to whom the rules do not apply. He was consistently and manifestly on-brand.

Biden, again, is supposed to be the statesman who can beat Trump, the one who invoked beating up a bully behind the gym to capture how he’d confront Trump and force him to cower. But he did none of that. Instead, he was derailed, he got interrupted and talked over, and instead of confronting Trump over calling fallen WWI soldiers ‘losers’, he had to pivot to explaining his son Hunter Biden’s drug problem. He was not the guy who takes the bully behind the gym for a beating – he was the guy who hands over his lunch money and hopes that somebody else sees it and tops it. But even the moderator who saw it all go down was digging in his pocket for nickels to hand over.

Again, Trump’s political brand is that he is strong enough to break rules without consequence. He cheats on his taxes, he lies to the banks about his assets, he sleeps with adult film stars after his wife gives birth, he lies about the virulence of COVID, he holds US foreign aid over the heads of states that can do him favors, he refuses to submit to Congressional oversight and inquiry, he benefits from government use of his properties, and he colludes with foreign powers to manipulate election information. And nothing happens to him. Nary a consequence. And in the debate, Chris Wallace the moderator repeatedly invoked the norms of debate with Trump. And following the brand, Trump ignored him and did what he pleased. Trump simply was what he’d promised he’d be – the guy who breaks the rules with impunity. And if the rules get written to really get him this time, he’ll break those, too.

Why would I allow the Debate Commission to change the rules for the second and third Debates when I easily won last time?

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 1, 2020

Book One of Plato’s Republic is devoted to a particular character, the sophist Thrasymachus. According to Thrasymachus, rules of justice are always rigged. They’re constraints imposed by the weak on the strong. According to Thrasymachus, then, to follow the rules, to invoke some law or state some principle, is a sign of weakness. The strong don’t argue, or look to the referees, or hope for some well-written statute to fix things; the strong do, the strong win, the strong take. The rules aren’t only for the weak. Following them makes you weak. Consequently, the ideal is the person who can break the rules with impunity – that’s Thrasymachus’ ideal of the truly strong man, the truly free man.

This picture of the immoralist and the attention it holds for too many is what the rest of the nine books of Plato’s Republic is out to answer, critique, and ultimately dispel. But notice that all of talking and philosophical argument may result in a correct diagnosis of the immoralist, but it nevertheless is impotent in the face of the immoralist before you. In the Republic, Socrates begins by silencing and humiliating Thrasymachus before turning to the full-form argumentative refutation. Socrates was not going to let him win as a disruptor of well-run critical dialogue, he was not going to let him break the rules without consequence. He shut him up, instead of telling him to shut up.

The first debate lacked that kind of reply to Trump – a repudiation of his brand. Instead it was Trump enacting his brand and everyone looking on as bystanders to and victims of it happening yet again.

That Trump won the debate is not good news at all. It is bad news for us as citizens, starting in terms of what prospects there are for counterpoints to those who think of themselves as above the rules. Further it is bad news for democratic politics, too, since the argumentative edge to the political display of branding is a test for how accountable these people will be once in office. Will they play by the rules? Trump has shown himself clearly unwilling to be bound by the rules, and so this bodes ill for either electoral output in November – if he wins, it’s four more years of an executive who obeys no norms; if he loses, it’s not clear he’ll see himself bound by the results. And a correlate worry arises with respect to Biden. If he does win the election, will he be like Socrates who can silence the bully, or will he be more like the kid who is already getting out his wallet when the schoolyard bully approaches? If it turns out to be the latter, let’s hope that the moderators for the election have more tools for correction than Wallace did for the debate.