by David Oates

In my preceding post, I reflected on the poetry of the eighth-century Chinese master Tu Fu, which has nourished me for decades (in translation, of course). Tu Fu found a way to place himself both inside and outside the whirling political disorder of his times. I drew strength from the quiet inwardness he captured even in unquiet times. I have taken it as my model.

Yet Tu Fu lived under an entrenched monarchy. There was no hope of influencing or reforming it. So he maintained a joyous, half-brokenhearted inwardness instead. But the stance of “inward exile” (as Russian poets and dissidents named it during the Soviet regime) – isn’t it more problematic when you’re living in an actual (if deeply compromised) democracy?

Isn’t more required of me – more courage, more participation? Especially when the struggle for democracy is playing out so vividly and courageously in my own town of Portland, Oregon, just a half-hour stroll downtown from my house. Why am I not showing up?

* * *

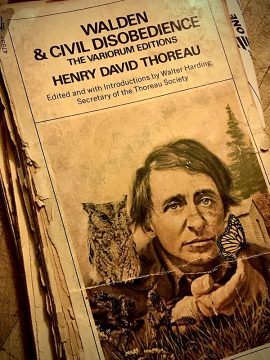

I always think of Henry David Thoreau when I get to this point in the meditation.

Thoreau famously lived alone in a shack for two years (1845-47) at a little lake in the woods outside Concord, Massachusetts. He published his strange book Walden, or Life in the Woods after nine years of laborious rewriting.

He had staked his life on the belief that anyone who actually paid attention to his or her own life would be transformed into so fully human a human being as to stop traffic. “There is not one of my readers who has yet lived a whole human life,” he wrote. “Most have not delved six feet beneath the surface, nor leaped as many above it. . . . Beside, we are sound asleep nearly half our time.” To this end, he celebrated the lowliest details of his life by the pond – counting nails, planting beans – as if they were amazing adventures.

“Be rather the Mungo Park, the Lewis and Clark and Frobisher, of your own streams and oceans: explore your own higher latitudes. . . . Every man is the lord of a realm beside which the earthly empire of the Czar is but a petty state.”

Awakening was his great metaphor. Wash the sleep from your eyes, “arise free from care and seek adventures.” He meant adventures of the spirit and of the mind, as much as physical ones – for “reality is fabulous:” “If men would steadily observe realities only, and not allow themselves to be deluded, life, to compare it with such things as we know, would be like a fairy tale and the Arabian Nights.” That fabulous.

Walden is a wake-up call, a celebration and a reminder that renewal is as near as the morning.

* * *

I took Thoreau’s example seriously and for much of the first half of my life sought clear mornings and mind-cleansing adventures. Mired in an abusive religiosity. . . wondering how to make a life out of my not-at-all-straight-ness. . . horrified by disco culture with its commodified sexuality, its drugs and cheap distractions. . . I headed for the mountains. Usually with my paperback Thoreau thrown (in its protective baggie) into a zipper pocket of my Kelty pack. A book of botany or geology or ecology beside it. Land maps, star maps. And some reading to keep Mr. Thoreau company – Tu Fu, Robinson Jeffers, Camus or Grass or Brautigan.

And, Reader, it worked. Staring into the tiny fire of a solitary campsite, ringed by the stunted pines and shining granite of a high tarn in the Sierra Nevadas, I found permission to rest. Under an eternal sky studded with incomprehensibility, my chattering mind quieted. Ensconced in a swaying forest of Jeffrey pine and incense cedar, or chugging stubbornly up a high pass, my self-loathing diminished. Really just shrank down to near nothing.

Withdrawal was my cure. Sometimes with one or two fellow hikers. Sometimes as a backcountry guide for a shoestring “outdoor-education” outfit. But mostly on my own. Year by year. Day by day. Step by step. Breath by breath.

* * *

Thoreau withdrew during parlous times. While he lived at Walden Pond, mostly solitary and seemingly rather self-involved, his country declared war on and invaded a nearly defenseless Mexico. Of course, literate and humane and right-thinking people condemned the aggression. Of course it went on anyway. The new territories won by conquest tore open the unhealed wound of slavery, setting off conflict and bloodshed that never ceased until another war settled the question. And Thoreau’s friends – Massachusetts intellectuals and political activists – scolded him for abandoning his social duties, saying “that it was not possible to do so much good” as a lakeside hermit. He ought to be leading rallies or writing abolitionist tracts.

Thoreau was not impressed. “Doing-good” was not his calling, he said – he had tried it and it didn’t agree with him. “Let every one mind his own business, and endeavor to be what he was made.” Simple as that: discover, and be, who you are. It can seem a wholly quietist answer, devoid of social conscience.

His friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson was scandalized, disappointed. Emerson owned the woods his young friend had retired into, and Emerson was nothing if not a good-doing citizen. His posthumous article memorializing Thoreau, though full of admiration, contains this curiously bitter complaint:

“With his energy and practical ability he seemed born for great enterprise and command. . . I cannot help counting it a fault in him that he had no ambition. Wanting this, instead of engineering for all America, he was the captain of a huckleberry-party. Pounding beans is good to the end of pounding empires one of these days; but if at the end of years, it is only beans!”

Yet here is where the picture of Thoreau gains an almost unearthly beauty. For the other piece of writing we remember him for is, of course, the essay “Civil Disobedience.”

Exactly half-way through his stint at the pond, Thoreau walked to town to get some shoes cobbled, had a chance encounter with Sam Staples the tax collector, and was clapped in the county jail for his six-year refusal to pay a state “poll tax” or head tax. Thoreau’s resistance expressed his disapproval of American slavery and foreign aggression. “Under a government which imprisons unjustly, the true place for a just man is also in prison,” he reasoned.

He got out the next day, the money paid by a friend or possibly his Aunt Maria. Hardly an epic of heroism and oppression. . . more like the gentle scrape of a privileged white man. Yet the essay generated from this “action from principle” was of such potency that during the next twelve decades it would destroy global empires and bring down American citadels of bigotry.

Emerson’s sarcasm became ironic prophecy: pounding beans did indeed lead to pounding empires. The huckleberry-captain commanded more divisions than the British empire could resist, with South African and American police squads and actual Nazis thrown in.

Here’s how it happened. In 1907, young Mohandas K. Gandhi, agitating for Indian civil rights in South Africa, reprinted the then-obscure “Civil Disobedience” and distributed it, pamphlet-sized, by the thousands. Later it became his reliable weapon as he dismantled the British Empire in India. A generation after that Martin Luther King, Jr., inspired by Gandhi, also read Thoreau, and from these sources developed his program of “non-cooperation with evil.” And in the meantime, during World War II, the Danish Resistance had taken the little booklet as virtually a manual of operations. King Christian’s celebrated donning of the yellow star, in solidarity with threatened Danish Jews, was but one result.

Imperious masters on four continents were ultimately routed by the quiet non-activist Thoreau (in the hands, of course, of his decidedly more activist followers). I wish it were more often remembered that Henry David Thoreau had thus written two of the world’s basic texts – on both sides of the perennial dichotomy of active engagement versus contemplative withdrawal. “Civil Disobedience” and Walden bracket the problem.

Most of us fall simply into one character-type or the other: unquiet political ranter or squeamish navel-gazer. During my years participating in the Society of Friends (“Quaker Meeting,” with its core tradition of silent collective meditation matched with an equal tradition of vigorous political activism) I noticed how neatly our membership sorted themselves into activists and contemplatives. Complementary types. . . we hoped. It was tricky, always a work in progress.

Thoreau united the question by grounding action in being. He did not listen to well-intentioned admonitions. He did not act in response to external morality or pressure to “do good” in some generalized sense. His acts and his words came from the same essential space: “Say what you have to say, not what you ought.”

“I came into this world, not chiefly to make this a good place to live in, but to live in it, good or bad.” He understood that his calling was not organizing, not pamphleteering, not reforming. His calling was Thoreau-ing, which meant living attentively and writing with all possible care and craft. He had the sense to see that only thus could he make his contribution. “The best you can write will be the best you are,” he noted in his journal.

Of busy reformers mired in unexamined lives, he pointed out the limitation: “They speak of moving society, but have no resting-place without it.” A moral lever is useless without a place to stand. The quiet life beside Walden Pond was his standing place.

* * *

At Quaker Meeting I learned something surprising. The activists in our Meeting told me that they felt they gained something essential from the quality of quiet brought to our silent meditations by the non-activists. The political types were some righteous campaigners, I must say – their passion and selflessness left me in awe. They clearly felt a calling, and I could see that they had a knack for it. A gift.

And they felt that we contemplatives had an equal and corresponding gift, which they were nourished by! In my engrained American-style individualism, I had never imagined such a thing. At our Sunday “Meeting for worship,” the activists apparently drew strength from the centered openness we built there, all together in that silent hour punctuated perhaps by brief words. The activists needed to be reminded that their struggle was grounded in the mystery underneath all human busyness (or quietness) – that place from which selflessness and kindness and, at its best, democracy emerge. That Mystery from which life itself emerges.

* * *

Thoreau and Tu Fu tell me to be in my life and to write it with all due ferocity. That if I do this right, it will lever out into the world in ways that my getting punched up at a midnight protest never could.

I can see ways this has come true. A few of my books have tried to translate solitary wandering into communal insight, inspiration, opportunity. I’ve written about the natural world, and about the place of beauty, music, and art. About the struggle to define community communally (instead of through the dictates of profit). A writing group I convened just after the current president’s election put out the good word: In dark times, to speak the truth first we must seek each other. We published a book about it.

I should admit that my reluctance to go downtown to the nightly imbroglio also has private and idiosyncratic roots. I’ve spent a lifetime staying out of the reach of gay-bashers and maintaining a hygienic distance from spewers of Godly hate. My life has needed me to be committed to my own non-victimization. I find it almost impossible to intentionally put myself in harm’s way. And on the practical side there’s the simple fact of my body’s unsuitability – at this late stage it’s a Rube-Goldberg contraption of damaged joints, weakened muscles, and questionable cabling. (Yet others of my age are out there every night. . .)

Oh, we are many things, aren’t we? I see the cowardice in my choice. And the wisdom. And the missed opportunity for solidarity. For beneath the smoke and fury is a truth: our fate is each other. And this moment of protest is clearly about acknowledging this us-ness. That what happens to another, happens to me.

It’s seven o’clock. While my neighbors shout and clap and sing from their doorsteps, brother and sister activists are preparing to go downtown. To support a slogan and a movement, Black Lives Matter. To remember the names of those slain by a deranged policing system: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery. . . . To confront a government of strangely exposed authoritarianism and naked violence. They will be doing this work for all of us. With all of us.

Sources/References:

Walter Harding, ed. and Introductions, Walden and Civil Disobedience: The Variorum Editions (Washington Square/Pocket Books, 1967). For background information and the authoritative texts.

Emerson’s elegy/encomium for Thoreau is in the August 1862 issue of The Atlantic.

Odell Shepard, ed., The Heart of Thoreau’s Journals (Dover, 1961). I’ve quoted Thoreau’s entry for Feb. 28, 1841.

Jill Elliott and Alison Towle Moore, eds., Come Shining: Essays and Poems on Writing in a Dark Time (Kelson Books, 2017). The book we produced in response to the 2016 election.

Photo credit: Horatio Law