by Sabyn Javeri Jillani

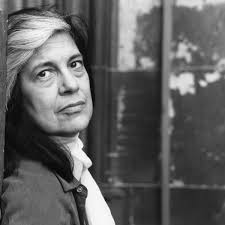

‘To be a woman is to be an actress’, writes Susan Sontag in her 1972 essay The Double Standards of Ageing. She is referring to the beauty norms that expect women to freeze ageing while levying no such expectations on men. As the popular saying goes, men become wiser with age while women become older; men being judged by their maturity while women through their bodies. Beauty is often associated with the young and so these pressures of eternal youth trap our subconscious in unrealistic standards of attractiveness. Performing to a biased audience, women become objects of their own calling for as Sontag writes, ‘From early childhood on, girls are trained to care in a pathologically exaggerated way about their appearance’. She wrote this nearly 50 years ago. Since then, there has been a lot of consciousness-raising debates about these reductive attitudes, and nowadays you would be hard pressed to find someone who would admit to the pressures of ‘youthful preservation’. They call it ‘selfcare’, instead. But is it really?

I’ve always been suspicious of dressing up to please others but I’m even more skeptical of dressing up for myself. Despite all the consciousness-raising feminist movements that made us aware of women’s history of objectification, the fact remains that prior to the pandemic many of us still spent a lot of time and money on beautifying ourselves according to societal standards. Only this time the capitalists were selling it to us as ‘selfcare’ and ‘wellbeing’. The pandemic has made us rethink how beauty and youth have been rebranded as ‘selfcare’ while still pandering to the imaginary audience that makes being a woman a performance. Much along the lines of Sheryl Sandberg’s neoliberal ‘Lean in’ feminism which tells women to take responsibility for their marginalization, the new beauty standards tell us to look good ‘for ourselves’. In other words, looking good is for our own good.

This may sound strange in today’s so called post-feminism world, where fear of ageing is a contested, and to some, an outdated topic. Media and influencers tell us that more and more women are embracing their age rather than hiding it. Ageing is empowering – but only as long as you don’t smell of decay and retain that youthful glow of energy about you. For the truth is, the beauty industry has altered and adapted to this new ‘empowered’ mindset, selling us old wine in new bottles. Purchasing ‘anti-ageing’ potions and lotions that cost an arm and leg is not marked as indulgence, it is now sold to us as an ‘investment’ in one’s self. The rhetoric of beauty has changed and it’s not unusual to hear women rationalize it as enfranchisement, but is it really?

Before the pandemic, I would often hear women friends say: ‘I put on makeup for myself. Not to please others,’ or ‘I buy expensive anti-ageing creams to invest in my skin, not for anti-ageing reasons’, or ‘I use botox and fillers to look fresh, not to fight age’, ‘I buy expensive lipstick because I like how it makes me feel’….And perhaps, earlier this year, I too, would have found myself saying this.

But five months into the pandemic my views have changed. I find myself wearing comfortable clothes, I have let my roots grow out and I dress for comfort rather than style. Now I look at the painfully excruciating high heel shoes or oxygen cutting skinny jeans in my wardrobe, the tubes of concealer in my drawer, the unused vials of hair dye, and I think to myself- was I really dressing for myself? If so, then why do I not continue to do so when there is no one around to see me?

I am reminded of Sontag’s words, ‘Being feminine is a kind of theatre, with its appropriate costumes’. With no audience around, has the desire to perform receded? Or is it that somewhere along the way, despite the consciousness of toxic femininity, we internalized the thought that, as women, we will always be judged by our appearance. And as older women, judged even more harshly as ‘dowdy’, ‘frumpy’ or worse, ‘negligent’, if we let the mask down.

The rhetoric of ‘selfcare’ has convinced us that we ‘perform beauty’ to please ourselves. But now that many of us have relaxed our rigid ‘wellbeing’ routines, we find ourselves questioning if our audience really was us? Many of us are rethinking the jargon of ‘selfcare as downtime’, for we seem to indulge in these routines and rituals of dressing up only when we are being viewed by an external eye. Many female colleagues tell me that they ‘slap on a little lippy or change into close-fitting clothes just before a zoom meeting,’ because they want to look ‘presentable’. With the camera off they relax and get back into comfortable clothes, wipe off the lipstick, or pile their hair up into a messy bun. With no audience to judge us, why do we not indulge in those elaborate rituals of ‘selfcare’ if the aim is really to dress up for ourselves?

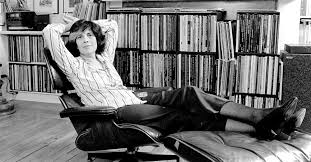

With this realization, many of my wonderful women friends have taken the lockdown as a time to let the gray in their hair grow out. Others have embraced their curves and now wear clothes that fit them rather than forcing their bodies to ‘fit the fashion’ by starving themselves and challenging their ageing metabolisms with strict diets. They sit comfortably with legs stretched out or backs hunched, unsmiling, in whatever posture or expression seems comfortable. The self-consciousness that comes with being watched seems to have dissipated, a little. Perhaps because we no longer feel vulnerable in our desires to conform to internalized gender norms. Although the price of such a non-conformist attitude can be harsh.

One colleague reflected with horror that she would never sit in public, the way she does in zoom meetings where the camera only captures her top half. Another noticed how much she had to smile to come across friendly and approachable in the work space, and how she can now relax her facial muscles while working from home. I thought about how many times I had witnessed male colleagues’ manspreading or mansplaining and frowning without any sort of self-consciousness, be it in an open plan office or in a board meeting. Neither is this uncommon in public spaces or on public transport. In the tubes and buses of London, I remember many male travelers would think nothing of jamming their elbows on the armrest or would let their thighs flop apart encroaching a fellow passengers personal space or merely stick their legs out in front of them without realizing how uncomfortable they might be making the person next to them. Why, then, did my women friends feel this was somethings they could do only in the privacy of their homes? Perhaps because if they were to sit on public transport or in an office with their legs stretched out, they would be judged. Older women, even more so, with their maturity and sagacity being questioned. Is it then this performance that Sontag refers to that keeps us from facing the world without our masks of make-up and styled hair, whether we call it ‘skincare & haircare’ or ‘selfcare’?

Now with the pandemic questioning this idea of ‘performing beauty’ the beauty and youth industry, too, is quickly changing targets. Julie Cresswell wrote in The New York Times that with more women dropping elaborate beauty routines during the pandemic, ‘Beauty brands, acknowledging their products are nonessential, are also having to navigate how to unveil new products and market themselves without coming off as insensitive to the health and economic crisis that is unfolding. Revlon, for instance, started the social media campaign #butithelps, encouraging followers to put on their favorite lipstick, even if they’re just wearing sweatpants at home.’

Crewell’s words have brought out the insecurities of ‘performing beauty’ that have us questioning the need to do so with a limited audience and by default, admitting that it is a performance. Now that so many of us have adopted comfort over style, letting go of ‘performing’ has also become an act of empowerment. Appearing in public without make-up is for many of us. Perhaps because it makes us feel exposed. But the word expose has to my mind always been related to reveal or confess- again an act of shame. Just like women’s writing is often termed confessional writing (with its negative connotations of sin and repentance), women baring their unmade faces or ageing bodies, too, is associated with a shame that has to be covered up. For exposing ourselves as we are, means ‘accepting’ ourselves as we are. It means ‘selfcare’ and ‘wellbeing’ becomes accepting our age instead of trying to fight. It means that it would be ok to go gray, to have wrinkles, to not have the same energy as someone 10 years younger. It means we stop conforming.

But how many of us can really afford to do that in an age where women who refuse to conform are shamed for ‘letting themselves go’? It is a question that makes me think of Sontag again, for she writes, ‘Women have been accustomed so long to the protection of their masks, their smiles, their endearing lies. Without this protection, they know, they would be more vulnerable’. During the pandemic, by letting ourselves go gray, by accepting our ageing bodies and by dropping the façade of demanding selfcare routines, many of the women I know have finally let go of the ‘theatre’ that made them vulnerable. And by embracing our vulnerabilities, we have come out stronger. As writer Sara Atnikov wrote in CBC’s Pandemic Diaries, about feeling liberated from imposing beauty standards during the pandemic, ‘Everyone’s lives look different than they did three months ago, and who knows what our futures will hold. I think mine might have a little less makeup, and I think I’m going to try and embrace this new forced vulnerability. It can take that place in my foundation where the need for perfection used to be.’

If there is one thing that the pandemic has taught us, it is that control is an illusion. And if perfection is about control, perhaps it is time to lose control. From the mightiest of world leaders to the fittest of athletes, we are all vulnerable today. The uncertainty of our times has made us understand that what matters most is treading that fine line between truth and fact for as Sontag said, ‘Women should allow their faces to show the lives they have lived. Women, should tell the truth’.