by Jackson Arn

Writing seriously about comedy is a thankless challenge. Only an idiot, or somebody who’s used to thankless challenges because he’s a freelance critic, would bother. The risks are high, the rewards low. Overanalyze your subject and you’ll kill it. Treat it too indulgently and you’re left with a jumble of second-hand bits. Clearly, jokes say something important about the society that laughs at them, but woe to the writer who takes them too literally or too earnestly. They are, after all, jokes.

Sometimes, comedy changes so profoundly that it’s worth risking some kind of grand, straight-faced interpretation. And mainstream American comedy has changed profoundly in the last thirty-ish years. It’s gotten thinner, lighter, you could almost say healthier. The style of humor that nourished America for decades has dried up—it’s still possible to find it if you know what to look for, but it’s become the exception where it used to be the rule. To put it another way: comedy has been drained of chicken fat. Where did it go?

If my subject is chicken fat, I have to start with Mad Magazine. No humor source—not SNL, not Carson, not Lenny Bruce—had as much influence on America in the back half of the 20th century. This is impossible to prove, and almost certainly true. Mad was founded in 1952 and lasted until 2019, when it announced it would stop printing new material. At its peak it had two million subscribers. It made its reputation poking fun at McCarthy and Khrushchev and lasted long enough to take on Trump and Putin.

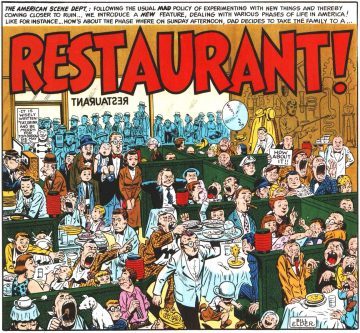

Unlike Lenny Bruce’s standup or The Tonight Show ca. 1962, early issues of Mad are still laugh-out-loud funny. Their style of humor is familiar but unnerving—you have the sense of sampling a potent, not entirely pleasurable drug that you’ve otherwise only tasted in watered-down forms. In a 1954 feature called “Restaurant!”, the splash includes a couple dozen rubbery bodies squishing against each other like blobs of color in a lava lamp. The title is the only simple part—there’s nowhere in “Restaurant!” to rest your eyes. Every square inch is lousy with stuff: hieroglyphics; a pair of kids slugging it out; a tower of dishes that’s about to fall over; more gaping, black mouths than you’ll find this side of Francis Bacon; an orangutan.

This was a comedy of abundance, of jokes on top of jokes on top of jokes—in other words, chicken fat. Its inventor, or at least the one who named it, was a cartoonist named Will Elder. He was born in the Bronx in 1921; his real name was Wolf William Eisenberg, but like a lot of pragmatic Jews of his generation, he opted for something Waspier. A self-described student of Bosch and Bruegel, he has a fair claim to being one of the greatest draughtsmen of the last century. He was a very funny guy, and also a huge pain in the ass. I suspect so, anyway. As a child he convinced his neighbors that a man with a knife was trying to kill him. He once painted a portrait of his young son and then added two tiny, vampiric dots to the neck. On Valentine’s Day he’d send his sweetheart beef hearts from the slaughterhouse.

Elder’s great insight—the basis for Mad’s house style, and a good chunk of comedy for the next fifty years—was that you could pack the panel with little gags and doodles and caricatures and still keep the overarching story. The little gags enriched the “flavor” of the comic without overwhelming it, as chicken fat enriches the flavor of a soup. Elder’s drawings for Mad were cluttered, but carefully, painstakingly so—narrative and fragmented, traditional and avant-garde, artful enough to stand on their own but taut enough to propel you onward to the next panel.

And Jewish. Jewish at every level, really: the chicken fat style was pioneered by a Jew, named after a staple of Jewish cuisine, imitated by the other outer-borough Jews who made up Mad’s freshman staff. Its machine gun pace was pure Jewish vaudeville; its raunchiness was a pin aimed at the soft, white backside of goy America. The way Elder had conceived of chicken fat humor could almost be called Freudian—by throwing out more jokes than the mind knew what to do with, he created a kind of comedy that worked semi-subliminally, tinting your mood whether you knew it or not, creating an illusion of depth.

At some point in living memory, it’s been said, Jewish humor became humor, full stop. In the case of chicken fat, I think this is basically true, or was for a long time. Mad’s influence was such that it brought chicken fat to a full generation of budding comic geniuses across the country: Terry Gilliam in Minnesota, Robert Crumb in Pennsylvania, David and Jerry Zucker in Wisconsin, Matt Groening in Oregon. Outside the country, too—the French New Waver Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Métro (1960) seems suspiciously like a live-action Will Elder cartoon. (Lest I make it sound as if Mad invented the concept of dense, detail-oriented comedy, it’s worth noting that Jacques Tati’s Playtime, from 1967, could be the chicken-fattiest film ever made—anyone who claims to have spotted all its gags after one viewing is either lying or nearsighted.)

Chicken fat even trickled into the work of comedians who were on the scene before Mad existed. Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles (1974) is plainly a post-Elder comedy—take the bit where the villain holds auditions for his gang of henchmen. The camera pans down the line: first the obvious cowboys, but then 50s Greasers, German soldiers, bikers (with the handles growing out of their legs), Klansmen (with “Have a Nice Day!” stenciled on their robes), etc. It’s the sort of thing you’d find squeezed into the corner of a Mad strip, as is the scene in Airplane! (1980) where people take turns slapping a passenger out of hysteria—first a flight attendant, then a doctor, then a nun, then a guy with boxing gloves, a wrench, a bat, a handgun …

Recently, some bright sparks decided to count and rate every joke in Airplane!. The results read like a golden-age Awl feature, or maybe an early, unpublished Tao Lin novel. Sample entries, with rating from one to 10 noted parenthetically: “153. There’s actual jars of mayo at the Mayo Clinic. (3.71)”; “80. Ice cream cone instead of microphone. (6)”; “157. Dr. Rumack grows a Pinocchio nose telling the passengers everything will be fine. (3.57)” According to the article, there are 178 jokes in Airplane!. That sounds a tad low (they appear to have missed one of my personal favorites, which involves a lowrider ambulance stretcher), but you get the idea. In a 90-minute movie, 178-plus jokes come so fast it’s impossible to process them all, and after a while they start to melt into each other.

I’m not saying that more jokes are better than fewer—only that when a film is a joke a minute, or literally two, and most are actually funny, the result is something greater than the sum of its parts. Like all styles of comedy, chicken fat communicates a certain view of the world. And the worlds of Airplane! or “Restaurant!” or The Simpsons are filthy factory floors covered in bodies, machines, signs, and food. Nothing is central, nothing is essential, almost nothing is connected. Nature barely exists. Because of the speed at which new gags are discharged, everything seems like a gag, or like it’s about to mutate into a gag. The main characters cling desperately to the plot, but the only reason we care about them is the chicken fat that’s always on the verge of drowning them.

What I’m describing is, save for the humor, a nightmare—specifically, the nightmare of jittery metropolitan life that Elder and the rest of the Mad staff grew up with. But if chicken fat suggests such a worldview, it also paints a portrait of its own audience, and this portrait is more flattering than you might suppose. By offering more jokes than any single person is likely to get, the chicken fat comedian acknowledges that everyone is different. Chicken fat trusts you with the freedom to choose what to notice and what to glance over. It rewards your attention as well as your inattention. It acknowledges all the quintessential bad, modern feelings (alienation, distraction, confusion, paranoia) and redeems them by turning them into comedy.

All of which only makes it more puzzling that chicken fat has almost disappeared from mass, narrative entertainment in this country. The world that inspired the chicken fat style hasn’t gone anywhere—so where are all the dense, surreal, joke-a-second shows and movies and comics? What is the early 21st century successor to Monty Python, Playtime, seasons 2-8 of The Simpsons, Airplane!, Blazing Saddles, Mad Magazine? What even comes close?

Arrested Development, maybe, but it’s the exception to everything. A few recent cartoons have dabbled in chicken fat—when animators can draw whatever they want and viewers can pause and peruse any frame they like, there’s really no excuse not to. In one episode of Bojack Horseman, there’s a blackboard, glimpsed for maybe five seconds, covered in the names of next year’s Oscar nominees. Best Foreign Language Film: My Father the War Criminal, Old Marriage, Karate in the Woods. Best Supporting Actor: Mark Buffalo, Shark Rylance, Tom Hardy (Who Is a Cat). All these little jokes are hidden onscreen, like eggs of a certain festive, Christian variety.

But Easter Eggs and chicken fat are not the same, and the difference between the terms is narrow yet suggestive (suggestive, for starters, of how Elder’s style of comedy had to lose its Jewish tinge in order to win favor with what is still a de facto Christian country). Chicken fat may be the tastiest, most complex flavor in the soup, but it’s not the main attraction; its purpose, at least in theory, is to enrich the other ingredients. Easter Eggs are an attraction in themselves: the hunt only begins after the movie or TV show is over, the plot long forgotten or never processed in the first place. This, I think, explains how even the Easter Eggiest recent TV shows can be unapologetically cheesy as few chicken fat-laden entertainments of decades past were. Chicken fat ironizes plot, holding it in check, refusing to let it be. Easter Eggs work independent of the plot—they’re denser and often more elaborate than chicken fat, but also stealthier, content to remain in the background.

A pattern seems to be emerging. Chicken fat comedy was always a volatile combination of traditional storytelling and anarchic detail. In the 21st century, the two halves are more segregated from one another, both in individual works and in comedy in general. In cinema, you have a couple of thinned-down, intermittently funny options: the character-based dramedies of Judd Apatow, the infantile pyrotechnics of Adam McKay, and the meta flourishes of Phil Lord and Chris Miller, all of which have made me laugh hysterically but still tend to get unbearably corny by act three. The case of McKay is revealing: in the last couple of years, without warning, the author of the sentence, “The clown has no penis!” has pivoted to Serious, Important, Political fare, when any true fan can tell you his masterpieces are Step Brothers and The Other Guys.

As for the anarchic detail, most of it seems to have gone out of movies and onto the web. If the spirit of Will Elder lives on today, it’s in tart, snippety little forms that didn’t exist while he was alive—gifs, memes, links, Vines, TikToks, and so on. Maybe this is for the best. The conventional, long-form parts of chicken fat comedy were never that great, which is why nobody remembers the plots of Airplane! or Life of Brian—the throwaway gags are what stay with you. Chicken fat was always the best part, so why not make it the only part?

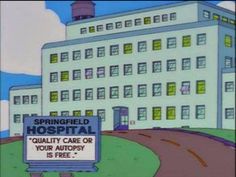

One reason, it seems to me, is that chicken fat is funniest when it’s confined to the background and then gives the action a run for its money. You can’t be a scene-stealer unless the scene belongs to someone else. When you see, in a Simpsons episode, a sign that says, “Springfield Hospital: Quality care or your autopsy is free,” you’re not laughing at the sign itself so much as the sign’s being there in the bottom left corner of the screen, waiting for you to notice it. When it comes to the fore, chicken fat loses one of its most valuable assets, the charm of discovery.

In short: chicken fat humor needs a silly, 90-minute plot and bland, not-so funny characters to cling to, as Lewis needs Martin and Groucho needs Margaret Dumont and Chet Haze needs Tom Hanks. It needs expectations to disrupt. It needs a canvas big enough to fill with wicked, merry nonsense. And these things are only possible when someone is willing to pay for elaborate sets and byzantine animation. In comedy, no less than in any other mass-market entertainment, it all comes down to a question of dollars and cents.

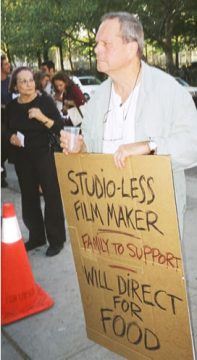

This time, the pattern is unmistakable. Mad lasted for two-thirds of a century, but its years as a lush comic book were over by July 1955—printing in full color was too expensive. Tati went bankrupt building intricate, city-sized sets for Playtime. Each new Terry Gilliam film is blessed with a tinier budget than the last (he showed up to the Tideland premiere with a cardboard sign that said, “Studio-less filmmaker. Family to support. Will direct for food.”). There has always been something financially unviable about chicken fat comedy, not despite but because of the fact that it’s overstuffed with jokes.

Think of it from a business standpoint: why expend all the extra energy conceiving of and realizing jokes that some people won’t get, or even notice? Why, once you’re sure that people will pay to see your movie or watch your show, add one drop of humor more? This might seem like—and is—a bizarre way to conceive of humor. It is, all the same, the kind of thinking that undergirds all mass entertainment—any surplus wit or originality are happy exceptions. And given the collective belt-tightening that has been the history of the new millennium so far, it’s not really surprising that comedy should have to play by the same rules.

It is strange, I’ll admit, to wax sentimental about chicken fat, a style that doesn’t give a damn about my or anyone else’s feelings. But I can’t help it. When I watch most recent comedies, even the ones people assure me are hilarious, I feel like I’m buying a 25-dollar chair from Ikea, some glue-and-plywood wreck that’ll start falling apart the second I sit in it, and may have been designed to fall apart, so I’ll come back to the store and pay 25 dollars more. Chicken fat comedy isn’t like this. Chicken fat is an antique armchair with dovetail joints and no knots, built to last. The more time passes, the more it seems like a relic of another era: an era when America was so rich it could afford to give away some jokes for free.