by Bill Murray

While everybody dreams of getting out of town, here’s the story of a mostly hapless road trip my wife and I took several years ago:

Ashray Raj Gautam waited in the dark before dawn. Men worked under the hood of his Toyota Corolla while we stuffed our things in its trunk. We pushed the car down the hill to get it started, and little Gautam took us to a town called Banepa, north of Kathmandu. Mirja bought junk food, I bought cheap Indian whiskey, and Gautam disappeared. When he came back he had a confession. He did a sheepish, dusty little shuffle.

“We came here with no fan belt.”

He was sure we could get one in Banepa but he couldn’t find one.

“Excuse me sir, we have to wait for new car from Kathmandu one hour.” He went to find a phone.

So we were off, sort of, driving from Kathmandu to Lhasa. Our Tibet travel permits would be waiting at the border. The fellow who booked us said don’t bring pictures of the Dalai Lama (I had five), and don’t be surprised if the police follow you – they’re not too used to private visitors.

Banepa, Nepal, was a lane and a half of bad tarmac twenty kilometers outside Kathmandu with twenty meters of dust on either side of the road, and businesses the length of town with their garage-door-fronts rolled down closed.

Buses bumped into the dust and blasted their horns. They shared the verge with chickens, goats, kids, bags of grain, metal rods and tubes, the general refuse, and us.

Two old folks worked the length of town with rough straw brooms, whipping up a dust tornado, moving trash from here to there to no use. Boys held up bread into the windows of the buses. They spit and coughed all the time.

The air was opaque. You couldn’t see even the neighborhood hills. Forget the Himalayas, you couldn’t see out of town.

Gautam borrowed 500 rupees for gas for the replacement Corolla. We needed oil, but we couldn’t find any and drove on. A road sign declared: “Khodari – 85 km.” The border.

For a few hours we drove up one side or the other of the Botaghosi. Bo means Tibet, Bota means from Tibet and Ghosi means river. It ran green and chalky and it ran wild.

People busted and stacked rocks. They dried homemade paper in the sun. Chalky dust covered everything. Thirty kilometers from the border the tarmac dissolved into rocks. Clouds drew closer (rather we to them). Now it was a meter by meter trudge. I was sure we’d break down but we bumped all the way into Khodari, sometimes along the river, sometimes on a track cut out of the hill.

Businessmen and thieves congregated on both sides of the border, and there were porters to pay to carry our bags over the bridge. We graduated from the Corolla to a LandCruiser, and headed into the border town on the Tibetan side called Zhangmu.

Our presence at the border attracted a driver, a “helper,” a Chinese minder, a businessman in a threadbare suit to handle it all, and a bully in a tank top, earrings, ponytail and Nike cap – expediter.

On the way out of town, a roadblock. If the guard is Tibetan he doesn’t care about your papers. Only the Chinese care about your papers.

Fifty kilometers to our destination, Nylam, steady gaining altitude. Where Nepal had huge pine forests, Tibet showed spruce and fir. Up the Botaghosi (must be named something else now), a first herd of Zoh – a mix of yak and bull – mingled with yaks, humps behind their shoulders and long hair, and then the trees just completely disappeared. Not there. Snow appeared on hilltops above. Beyond the Kathmandu valley the sky turned cobalt blue.

A row of tin-roofed sheds on either side of the Lhasa road, Nylam was nothing more. Up a ladder a no-name restaurant served dinner, pork fat, green chillies and fries.

Two horse blankets sewn together hung as the front door of the Nylam Snow Land Hotel, which was full. Our room was normally the proprietors’, with a sandal under my bunk. The girl who normally slept there slept on the bench behind the reception desk.

I feared for lice and Mirja for vermin. Mirja saw the pit toilet once and never ventured there again. At first light we lined up beside the other guests to brush our teeth outside the front door and spit our bottled water into the street.

Mirja stood by the LandCruiser and said something as I carried bags into the street.

“What?” I asked.

“Don’t step in the puke, I said,” she said, too late.

We set out alternately blazing downhill then crawling too slow up the other side of expansive valleys, ribbons of winding water at the bottom. Way, way down to the bottom.

A village called Pamas perched on a chalky, fast-flowing river. What was the river’s name?

“No special name.”

They made us understand that this river and others come from the Nylam pass, so collectively they are all known as Nylam rivers.

We’d drive alongside walled, multi-family settlements built of stone, with courtyards for livestock, which had their own way in and out. We’d pass a lone horseman, or three or four men with a horse-drawn cart. I thought the sun might not make it into the valley until noon.

We’d drive alongside walled, multi-family settlements built of stone, with courtyards for livestock, which had their own way in and out. We’d pass a lone horseman, or three or four men with a horse-drawn cart. I thought the sun might not make it into the valley until noon.

We didn’t quite understand why we’d drive so slowly up the inclines. Mirja suggested maybe it was a way to avoid landslides. Then, puttering across rocky plains, she suggested more weakly, school zones? Turned out our driver didn’t know “downshift.”

The boys passed between them strings of yak cheese. The Pakistani band Junoon on the juke, then some rasta tunes. “Stand up for your rights. Get up, stand up, don’t give up the fight,” our crew sang out loud with no irony.

Here was a landscape of stretched horizons. Patches of snow. Way up high, over 14000 feet, we felt light of breath. Things started to move a little bit in slow motion. Everything turned extra vivid, like in the seconds before a car crash. After a time we’d climbed so that there were ice fields in mountains down below.

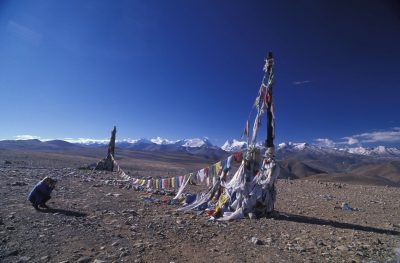

We stood a little tight in the chest, temples pounding, before the prayer flags at the Lalung Leh pass at 16570 feet, and gazed on the peaks of Xixibangma, at 26286 feet, to the west, and Cho Oyu (26278) off to the east in the Qomolangma Nature Preserve. Qomolangma is the local name for Sagarmatha, or Everest, and Cho Oyu is the highest peak in the range west of Sagarmatha.

We had a little engine trouble. The LandCruiser was idling low and they had to climb up under the hood to prime the carburetor. While they did, Mirja and I clambered back out for more of the view, cold, dry wind chapping our faces, and once the engine fired we moved on.

A sheep herd, pushed ahead by nomads, blocked the road. We jumped out of the LandCruiser into maybe forty people working the herd, most under thirty, about a dozen of them children. Two men carried crossbows and handmade fiddles on their backs. Tiny girls carried even tinier infants on their backs. A small boy scowled from his perch tied to the back of a donkey.

Beginning the traverse of a wide valley, we came face to face with Mt. Everest. Snow blew in waves off its peak. It was such a singular sight, Mirja and I piled out, just sat and stared. Our boys urged us on, saying we could see Everest better at the village of Tinggri, a hundred-meter-long settlement where we stopped for lunch at Amdo Guest House, ten rooms opening onto a courtyard. While the boys disappeared inside to eat, Mirja and I walked the town.

We traded caps with kids, took pictures of pony riders and bided our time. We inspected sacks of tsampa, the staple roasted barley flour, and the traditional houses, where old men or young kids drew water into canisters from courtyard wells.

While we waited back at the LandCruiser, mendicants and miscreants gathered at its windows. I went in to round up our team, who sat on long wooden benches in a darkened room. Everybody smoked and gossiped over butter tea. A cooking fire flared and lit up a half dozen men in the shadows. Ok, ok, one minute, they said.

I went back in fifteen minutes as the driver was just getting round to his noodles. I told them we had to go and stood there while he gobbled and slurped. My audacity, to haul them out of there after their hour and a half noodle break, sowed the seeds of doom.

For half the day we drove through canyons, along an escarpment and through an absolutely gorgeous painted desert. Dry, still, crisp and hot. An utterly clear sky. Nobody in sight anywhere except for us, and our new company. After lunch, out at the edge of Tinggri, our boys had made some phrases about, “she is going to Xegar,” and in popped an elfin woman of forty, who settled into the back of the LandCruiser on top of our bags. She coughed a lot.

So we were off with a hacking hitchhiker in the trunk and sullen staff in front. We got some slow Indian tunes on the juke, rolled our windows down for the breeze and settled in.

The wind howled as we climbed through settlements not on the map. The first power lines connecting to the east, to Lhasa and the grid, were just wooden poles with two wires strung along them.

Sometime past three, the engine stopped and the boys climbed back under the hood. We grew accustomed to piling in and out of the LandCruiser for mechanical reasons. The first time we sat on rocks our hacking hitchhiker shared Lao Lao Tang bubble gum with Mirja and me.

Then we set out across another rock field, did maybe twelve minutes and sputtered again. The first time your car breaks down in the developing world is de rigueur. The second time, if necessary, is included in the package. But now we sensed a routine.

Heavy patches of ice hung along either side of the road. At the next pass, even higher at 17060 feet, the dominant peak stood in snowy splendor. I asked its name.

Now, way back at the border, when we were happy to get a ride, we all introduced ourselves. Since then, I’d lost so much faith in the helper, whose rudimentary English was all we had, that I forgot his name, and our driver’s too, and now I didn’t care.

I named our driver “Noodleboy” in honor of lunch, and I just called our helper, “Sir.” Sir asked Noodleboy what the name of the peak was, they talked, and Sir turned to me, “No special name.”

The LandCruiser idled low but Noodleboy didn’t know to shift out of fourth when we’d brake to ease through streams. He wouldn’t apply gas, the engine would die, and we’d all hop out and take up our positions.

When we stalled right in the middle of a creek and a bus pulled up, blocked by us, somebody asked, “How long you been here?” We told them don’t worry, they’ll fix it in fifteen minutes, they’ve been doing it all day. The people on the bus thought that funnier than we did.

Once a LandCruiser with three Europeans and an English-speaking guide stopped to help. I explained to the guide how Noodleboy would let the engine die and they talked it over to no effect. That LandCruiser followed along with us for a while, as if to rescue us if our LandCruiser finally gave up.

This slowed them down considerably. Finally, at one repair stop, one Euro-guy slammed the door and theatrically started walking ahead into the desert (where was he going?) and I was secretly with Noodleboy when eventually we thundered by him and covered him with dust.

It was fifteen minutes to Lhaze, Sir declared. Forty-five minutes later when we asked how far now, he pondered and offered brightly, “about forty kilometers.” There was one last checkpoint. Just beyond it we had a flat tire.

Which was the crystalline moment between exasperation and acceptance. What had been a challenge was becoming a tolerably good story. So right there on the rocks by the road Mirja and the hitchhiker and I broke out the Bagpiper India whiskey that I carefully imported from Banepa, and toasted our boys fixing the tire.

Which was the crystalline moment between exasperation and acceptance. What had been a challenge was becoming a tolerably good story. So right there on the rocks by the road Mirja and the hitchhiker and I broke out the Bagpiper India whiskey that I carefully imported from Banepa, and toasted our boys fixing the tire.

Our hitchhiker showed us pictures of her two daughters, and her Dalai Lama amulet, so I slid her one of my smuggled Dalai Lama postcards. In gratitude, when we finally rolled up to Lhaze, she carried one of our bags and asked for a dollar.

•••••

In Lhaze, I pointed to the flat spare and asked if it would get fixed. They said it would. We agreed to leave for Xigatse at 8:00 tomorrow morning and the boys vanished. A young woman with a radiant smile led us up the guest house stairs by flashlight, down the hall to our room. They promised electrical power, but not until later, so we found a roadhouse across the street and talked with some men from Guangdong on their way to China’s Everest base camp.

We asked for cold beer and one of the guys tried to translate. The waitress looked puzzled, was gone too long, then came back smiling triumphantly, buckling under a big metal tub of raw meat. Translator thought we asked for “cold beef.” Good try.

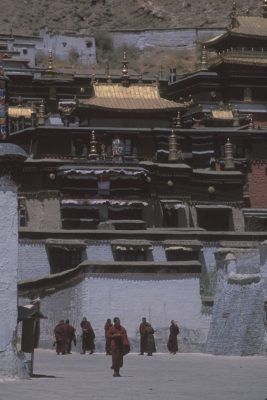

A table full of tourists from Szechuan played cards. One man saw a book I had opened to a page about the Tashilunpo Monastery in Xigatse and grabbed it from my hands. I slid him a Dalai Lama card and he grabbed it, too, and in an instant slipped it out of sight and inside his coat. They cooked up what smelled like breakfast sausage by lantern light.

The new moon provided no light, and back across the street it grew so dark the constellations blazed. The sound of conversation continued late into the night, kind sounds, singing and laughing.

Eight o’clock, agreed departure time, waiting on the gravel by the car. Our helper, Sir, showed up and said they’d have breakfast first. A man in a cheap suit interrupted, insisting “I need to talk to him.” I said I was talking to him. “Oh, you are special person!” His voice rose derisively, with a dash of menace. Not a good start.

We waited. In time the boys re-emerged with our hacking hitcher in tow. She’d be going with us again. And they hadn’t fixed the spare and they never did.

Mirja tried banter.

“It was loud last night. Was…there…party?” Pause. Blank look.

“Karaoke maybe?” She tried again. Recognition.

“Karaoke, yeah.”

“Do they do that every night?”

“Every night, yeah.”

A series of valleys stretched to the horizon, then again, and again. Snow patches on stark brown hills. Little cumulus puffs formed from nothing. Riding along, you could sit and watch clouds begin, and with a long horizon and plenty of time, that’s just what we did. A sing-along broke out to the cassettes.

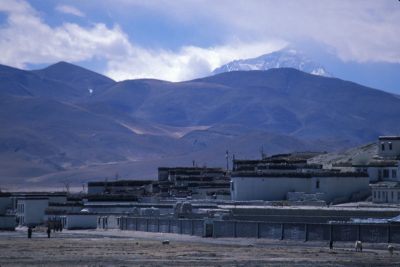

Xigatse is Tibet’s second city, former home of the Panchen Lama. These days there are two Panchen Lamas, the Tibetan one, kidnapped in 1995 and held incommunicado since by the Chinese, and a Chinese-appointed proxy largely rejected by Buddhists.

The Tibetan Panchen Lama’s former residence, the Tashilunpo Monastery, is one of the few monasteries China tolerates. Tashilunpo gave Xigatse a certain allure, but when we pulled up to a rogue hotel called Friendship #2 instead of our promised and paid for in advance Xigatse hotel – a hotel with toilets – the whole tenuous peace broke down.

I insisted we go the Xigatse Hotel. Our helper turned around full in his seat to talk to us for the very first time, and Noodleboy mouth-breathed faster. Sir exploded. In his very real anger, he made himself understood. I had done a bad thing when I dragged them away from their friends at lunch. All Chinese people eat lunch! He was just doing his job.

He showed me a list of the money he’d been given back at the border for our lodging. It included $15 for today. The Xigatse Hotel was $60, and he couldn’t pay for that.

He didn’t know how we did it in our country but in Tibet they did it the Chinese way. He declared, just short of fury, that we could pay to stay wherever we liked. No monastery tour for us today and tomorrow we leave for Lhasa at 8:00 sharp!

That was what we wanted, too. So everybody cooled off, they drove us over there and stormed away. We were pretty happy with that, and went off to find Tashilunpo.

•••••

I wasn’t giving them any excuse. I watched the sun’s first rays strike the prayer flags on the hill behind Tashilunpo from the front of the Xigatse hotel at 8:00 sharp. By 8:20 I was pretty discouraged and by 8:40 I found a tour bus driver who made me understand he was leaving for Lhasa at 10:00. While I puzzled through how to ask for a ride, Mirja called down the hall that our crew had arrived. Off we went, including the hacking chick, who was on a free ride all the way to Lhasa.

As a second city, much as I’d like to, I can’t say Xigatse impressed very much. Outside the Panchen Lama’s monastery there was little more than the barren, blue-collar, harried feel of a hardscrabble frontier town.

Mesas and mini-plateaus, eroded flat, stood alongside the tarmac road. No snow on the hills, no grazing animals. From higher vantage points, range after high range lined up ever more distant.

The closer to Lhasa, the more prayer flags, on a day as beautiful as you’ll ever see. We’d heard all the music the boys had by now and started it again. That was what our helper helped most with – tape changing.

Now settlements were surrounded by planted trees. Mule carts plied the roads; people walked along with shovels and farm tools. The Yalong River reflected the big blue sky. A winch system ferried people and animals across at four separate places.

The LandCruiser gave out in a village high on a hill surrounded by snow-capped mountains. Yaks were being put out while women filled silver urns with water at the spring, and prayer flags flapped over the river.

The LandCruiser gave out in a village high on a hill surrounded by snow-capped mountains. Yaks were being put out while women filled silver urns with water at the spring, and prayer flags flapped over the river.

After they got the Toyota restarted we hurtled headlong into a valley. Long haired goats. More prayer flags. Even as we broke down twice more it really was so beautiful (and we were close enough to Lhasa) that we’d already put our boys into past tense and just looked forward to a couple of days off the road.

Credit to the hitchhiker: We rode with her for three days and on each of them, while she wore the same outfit (in fact she carried no bags), she was always fresh. While the boys wore knockoff western styles made in China, she wore a local blue print blouse and cotton vest with her long skirt covered by an apron. She kept her hair bunned up with a blue headband. And she plied us with Chinese caramels.

Albania to Zimbabwe, Noodle Boy was the worst driver ever. He really would shift from third gear to fourth while meaning to accelerate to pass. Sir never got the client-provider relationship. A young Han Chinese man working at the edge of the empire, maybe he fashioned himself a contributor to a great enterprise, taming the heathen.

He wanted us to go with him to his travel agency boss, a Dutchman, in Lhasa, who he thought would make everything right. Instead we told him we’d call his boss and once Lhasa rolled into view we found our hotel, piled out, they wished us a good stay in Tibet, and all of us, I think, wished we’d acted better.

•••••

Congratulations to 3QD’s new contributors. I look forward to reading your work. Best of luck to you.