by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met here. I ask you to support artists wherever and however you can.

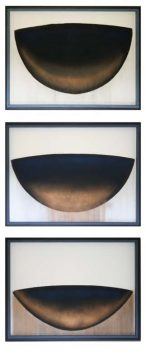

Peter de Swart, works on paper: Triptych

The triptych form is associated with religious painting. It first appeared as a feature of early Christian art and became popular for altar paintings and devotionals during the Middle Ages. While Peter de Swart’s Triptych is not overtly religious, it emanates an undeniably religious or spiritual aura. It is, in a word, numinous. To encounter this painting is to witness a sacred transaction. You’d have to be a stone to look at it and not experience a yearning for the divine. Why, apart from its rearticulation of the history and symbolism of the triptych form, is that?

It must have something to do, first of all, with the simple purity of the object pictured, which appears to be a bowl of some sort. Bowls are one of those inventions (like scissors or chopsticks or the hourglass) that we got right the first time. They were perfect the moment they appeared. In the bowl, function lives harmoniously with form. Its shape is so ideal as to be almost Platonic. Furthermore, bowls are used to prepare and serve food and drink, which means that they give sustenance, enable shared meals, and consequently help to strengthen communal bonds and deepen human relationships. Finally, bowls are vessels. Like hands and pockets and ships, they hold and contain and convey things—but they are not grasping like hands, nor like pockets do they secret away their contents, and they don’t trade goods and gold like ships. Quite the opposite, in fact: Bowls are generous, open, gratuitous. They give away the things they hold.

All of these attributes (form, use value, ethos) lend bowls a quasi-spiritual redolence, but they do not make bowls sacred. If this triptych depicted a bowl no different from any other bowl, then its effect would be decorative rather than numinous. This bowl is special. Again we must ask: Why is that?

This triptych tells a story of transfiguration, and its hero is the bowl. The bowl appears in the top panel as just a bowl. It fills the frame and contains some sort of pellucid substance, a kind of liquid-light. In the center panel, defying the laws of both physics and bowls, that substance gathers at the bottom of the bowl and (weirdly, almost supernaturally) begins to drain through it. At the same time, the bowl’s size diminishes—as though in losing its substance it is losing its mass. The bowl is weeping; its substance is escaping. Finally, in the bottom panel, the substance it held has drained out to such an extent that the bowl is suspended within it. It is a smaller and shallower bowl now, but its rim perfectly bisects and balances the picture plain. It lives in a state of equilibrium. The bowl has been diminished in size—but the picture has been enriched in substance. This bowl is special because it has been transfigured. We see through this work of art what the bowl always was and has become: It is a vessel of light.

Human beings are also vessels. We are living, breathing, moving vessels who are shaped by what we carry within and what we share without. This piece, the story of a bowl transfigured, reminds us that light cannot be hidden or contained, either in a bowl or a body. Light wants to be given. It is intended to be shared. This piece provides us with an example: If a bowl can do it, why can’t we?

Rachelle Reichert, Salt Diamond. San Francisco Bay Salt, steel, resin, wood panel, 2018.

Rachelle Reichert, Salt Diamond. San Francisco Bay Salt, steel, resin, wood panel, 2018.

Salt is essential to human health, and its availability has been pivotal to the development of civilization. It has been used throughout history to seal agreements, forge covenants, ward off evil spirits, attract patrons, preserve food, consecrate churches, finance voyages, and dispel negative energies. Cities have arisen and flourished on account of their adjacency to deposits of salt. Taxes have been levied and wars fought over it. Roads have been laid with the sole purpose of transporting it. Salt has been used as currency and directly traded for gold, ivory, slaves, skins, kola nuts, pepper, and sugar. One of the five basic taste sensations, salt is also a purgative, a salve, a flower, and a crystal.

You may want to touch Rachelle Reichert’s Salt Diamond; you may even want to lick it. Salt has that effect on us. Elemental, alluring, pure: It stimulates the appetite. We want salt. Like water, we want to bathe in it, feel it on our skin, ingest it somehow. Salt Diamond knows this. It knows us, and it knows our desires. It is one of those very rare pieces of art that seems to look back at and comprehend its viewer, one of those objects that in its material and compositional simplicity attains a kind of self-awareness approaching aloofness. It has weight, mass, presence. A Cycladic head comes to mind, or a colorfield painting, or a Suprematist composition. Like these works, like nature itself, Salt Diamond doesn’t care what we think or what we may say about it. It was created from material that was here long before we arrived and will remain long after we are gone. It is implacable. Unlike most of us, it closes the gap between what it is and what it claims to be. It is self-contained and fully self-actualized. It is the thing that it calls itself. It is not an example or a representation of a “salt diamond.” It is, simply, Salt Diamond.

This is terrifying and irresistible work. It has weight, mass presence. It is implacable. It draws you into its presence like the ocean, with a tidal pull; and like the ocean it remains steady even while shifting and moving with the changing light of each day, gathering and reflecting the weather outside and the mood of the sky. The frame is made from steel, which means that over time it will rust and shift and settle. That is intentional. Salt Diamond is a living, breathing thing that is subject to the same laws of inertia and entropy that all things are.

In a world of noise and flux and relentless flow, Salt Diamond waits and endures. Its stillness will call you; you may find yourself returning to its surface again and again. Created from crystals that the ocean deposits as it withdraws, it is saturated and sparkling with oceanic memories and experience. Within each mineral is contained a trace of the ocean’s surge and retreat—and a warning, should you choose to hear it, of the dessicating influence of human activity on our environment. Victorious armies used to scatter salt to prevent crop growth in lands they had vanquished. Could Salt Diamond speak, it might whisper that we are doing exactly the same thing, right now, on a global scale.