Robert Cohen at Lit Hub:

Someone must have been telling lies about Jared K., for one fine morning without having done anything wrong, or right for that matter—without having done anything save run a major metropolitan newspaper into the ground and kick thousands of poor people out of their apartments—he was put in charge of the nation’s pandemic response. This had never happened to K. before. Except for that time he was put in charge of the border wall. And opioids. And prison reform. And presidential pardons. And the Middle East peace process. “I’d better get someone in authority to help me,” K. said. But there was no one.

Someone must have been telling lies about Jared K., for one fine morning without having done anything wrong, or right for that matter—without having done anything save run a major metropolitan newspaper into the ground and kick thousands of poor people out of their apartments—he was put in charge of the nation’s pandemic response. This had never happened to K. before. Except for that time he was put in charge of the border wall. And opioids. And prison reform. And presidential pardons. And the Middle East peace process. “I’d better get someone in authority to help me,” K. said. But there was no one.

Now he stood near the podium in the briefing room. It was prime time. The camera was eyeing him with bland curiosity, as if it expected something significant from him, some comprehensive answer or consoling truth. But what? He recalled this feeling from his bar mitzvah, for which he’d worn more or less the same suit: this same atmosphere of suspended meaning, of people coming together to hear him read from the coiled scrolls of the Law, at once precise and obscure. Only what was the Law? It was so hard to read. Where were the vowels? Where was the rabbi his parents had paid to help him? When would his voice change, and a few lousy hair follicles appear on the backs of his hands?

More here.

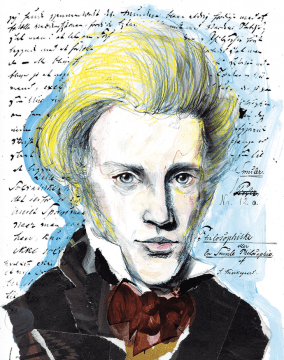

CH: Yes. I’m not sure atheism, as we now know it, was generally available as an option for 17th-century thinkers. By “atheism” I mean a total rejection of any sort of divine being. There may have been a few real radicals who proclaimed such a belief, but encountering them in those days must have been like meeting someone today who denies the existence of electrons. Some sort of divinity metaphysics was woven into the very fabric of metaphysics back then – maybe the biblical God, maybe a less specific divine person, maybe an impersonal divine force, maybe something falling between these notions. But to think that there wasn’t some sort of special being ushering into existence the world with its laws of nature must have seemed like a non-starter. Even Hume, in the next century, couldn’t shake the idea that there probably was some sort of Big Designer, if we take the conclusion of his dialogues to represent his view. It’s not until the 19th century, with the postulation of deep time, that atheism in our sense becomes really thinkable.

CH: Yes. I’m not sure atheism, as we now know it, was generally available as an option for 17th-century thinkers. By “atheism” I mean a total rejection of any sort of divine being. There may have been a few real radicals who proclaimed such a belief, but encountering them in those days must have been like meeting someone today who denies the existence of electrons. Some sort of divinity metaphysics was woven into the very fabric of metaphysics back then – maybe the biblical God, maybe a less specific divine person, maybe an impersonal divine force, maybe something falling between these notions. But to think that there wasn’t some sort of special being ushering into existence the world with its laws of nature must have seemed like a non-starter. Even Hume, in the next century, couldn’t shake the idea that there probably was some sort of Big Designer, if we take the conclusion of his dialogues to represent his view. It’s not until the 19th century, with the postulation of deep time, that atheism in our sense becomes really thinkable. Indeed, from the beginning, the popular response to Greta Thunberg has displayed some of the characteristics of a millenarian movement, as described by Norman Cohn in his classic study The Pursuit of the Millennium (1957). The millenarian movements of the Middle Ages, Cohn writes in that indispensable book, appealed to “an unorganised, atomized population”; they tended to take place “against a background of disaster” (plague, famine, economic crisis); they were “salvationist” in tendency (imagining the redemption of the world through struggle); they convocated around “intellectuals or half-intellectuals”, figures of humble rank perceived by their followers as prophets or messiahs, leaders who possessed “a personal magnetism which enabled [them] to claim, with some show of plausibility, a special role in bringing history to its appointed consummation”.

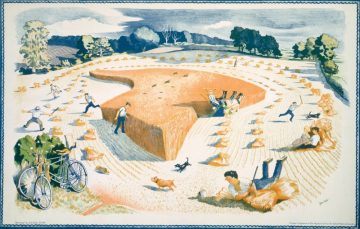

Indeed, from the beginning, the popular response to Greta Thunberg has displayed some of the characteristics of a millenarian movement, as described by Norman Cohn in his classic study The Pursuit of the Millennium (1957). The millenarian movements of the Middle Ages, Cohn writes in that indispensable book, appealed to “an unorganised, atomized population”; they tended to take place “against a background of disaster” (plague, famine, economic crisis); they were “salvationist” in tendency (imagining the redemption of the world through struggle); they convocated around “intellectuals or half-intellectuals”, figures of humble rank perceived by their followers as prophets or messiahs, leaders who possessed “a personal magnetism which enabled [them] to claim, with some show of plausibility, a special role in bringing history to its appointed consummation”. There is little evidence in Harvesting, a charming and amusing picture of harvesters, rabbit catchers, idlers and canoodlers that the artist, John Nash (1893-1977), was a painter haunted by his experiences of the First World War. In 1917 his regiment, the Artists Rifles, was involved in a counter-attack against the Germans near Cambrai. As the men went over the top, he recalled, there was silence and then: “Suddenly the Germans opened up and that seemed to be every machine gun in Europe…” Of the 80 men who climbed out of the trenches, only 12 returned alive and unfounded: Nash was one of them. Although his brother Paul was a better known war artist, John’s 1918 painting of the episode, Over the Top, poignantly captures the leaden-footed fatalism of the soldiers – not just weary but life-weary – as they trudge into no man’s land towards their deaths.

There is little evidence in Harvesting, a charming and amusing picture of harvesters, rabbit catchers, idlers and canoodlers that the artist, John Nash (1893-1977), was a painter haunted by his experiences of the First World War. In 1917 his regiment, the Artists Rifles, was involved in a counter-attack against the Germans near Cambrai. As the men went over the top, he recalled, there was silence and then: “Suddenly the Germans opened up and that seemed to be every machine gun in Europe…” Of the 80 men who climbed out of the trenches, only 12 returned alive and unfounded: Nash was one of them. Although his brother Paul was a better known war artist, John’s 1918 painting of the episode, Over the Top, poignantly captures the leaden-footed fatalism of the soldiers – not just weary but life-weary – as they trudge into no man’s land towards their deaths. The panic began the moment the earliest cases were confirmed. Those with means hurriedly packed their belongings and fled the city. Those who stayed had a range of reactions: many laid siege to the markets, stocking up on provisions before barricading themselves and their families in their homes; some congregated in churches while others consulted astronomers and fortune-tellers; many more, dismissive of the invisible disease or the visible fear it stoked in the masses, continued their lives unabated. These individuals were the first to die. The government acted swiftly. Invoking emergency measures passed in earlier times, the mayor issued a series of orders that aggressively changed life in the city. Public events and gatherings were banned, schools were closed and the city was divided into more readily policeable quarters. Infected individuals were locked in their houses with their families and were forbidden from leaving under the penalty of death. Upstanding citizens, deputized in various capacities as searchers, examiner, and watchmen, were — under the penalty of death — tasked with overseeing this quarantine. The city in question is not Wuhan or Milan or Manhattan. It is London and the year is 1665. Before the end of 1666, the Bubonic Plague will kill roughly one-quarter of the city’s population. As devastating as this figure is, it could have been much worse.

The panic began the moment the earliest cases were confirmed. Those with means hurriedly packed their belongings and fled the city. Those who stayed had a range of reactions: many laid siege to the markets, stocking up on provisions before barricading themselves and their families in their homes; some congregated in churches while others consulted astronomers and fortune-tellers; many more, dismissive of the invisible disease or the visible fear it stoked in the masses, continued their lives unabated. These individuals were the first to die. The government acted swiftly. Invoking emergency measures passed in earlier times, the mayor issued a series of orders that aggressively changed life in the city. Public events and gatherings were banned, schools were closed and the city was divided into more readily policeable quarters. Infected individuals were locked in their houses with their families and were forbidden from leaving under the penalty of death. Upstanding citizens, deputized in various capacities as searchers, examiner, and watchmen, were — under the penalty of death — tasked with overseeing this quarantine. The city in question is not Wuhan or Milan or Manhattan. It is London and the year is 1665. Before the end of 1666, the Bubonic Plague will kill roughly one-quarter of the city’s population. As devastating as this figure is, it could have been much worse. Throughout its history, philosophy has been marked by figures who sought to demolish the prevailing intellectual systems of their moment—to practice “philosophy with a hammer,” as Friedrich Nietzsche put it—in order to look with fresh eyes at the most urgent human problems. As depicted in Plato’s early dialogues, Socrates railed against professional Sophists who charged fees to engage in what amounted to rhetorical games. By contrast, he merely wandered the agora, posing pointed questions about life’s meaning to anyone who’d listen. He insisted that he had no new knowledge to impart: his wisdom lay entirely in recognizing his own ignorance. He devoted his energy to unsettling commonly held beliefs rather than imposing his own, and he spoke of himself as an annoyance, a gadfly stinging a complacent Athenian society. To much of that society he was a laughingstock, but he also attracted a substantial following, for whom his personal example—his ironic temperament; his embrace of poverty and his detachment from worldly matters; and, especially, his equanimity in the face of death—signified at least as much as the content of his thought.

Throughout its history, philosophy has been marked by figures who sought to demolish the prevailing intellectual systems of their moment—to practice “philosophy with a hammer,” as Friedrich Nietzsche put it—in order to look with fresh eyes at the most urgent human problems. As depicted in Plato’s early dialogues, Socrates railed against professional Sophists who charged fees to engage in what amounted to rhetorical games. By contrast, he merely wandered the agora, posing pointed questions about life’s meaning to anyone who’d listen. He insisted that he had no new knowledge to impart: his wisdom lay entirely in recognizing his own ignorance. He devoted his energy to unsettling commonly held beliefs rather than imposing his own, and he spoke of himself as an annoyance, a gadfly stinging a complacent Athenian society. To much of that society he was a laughingstock, but he also attracted a substantial following, for whom his personal example—his ironic temperament; his embrace of poverty and his detachment from worldly matters; and, especially, his equanimity in the face of death—signified at least as much as the content of his thought. India is the world’s second most populous country. Yet it boasts one of the globe’s lowest levels of public expenditure on health care, just 1.3 percent of GDP, less than a fifth of what the European Union countries invest. Knowing this, the government recognized the virus as a grave, perhaps catastrophic, threat. Public health officials heroically pursued contact tracing. “Social distancing” and “self-isolation” rapidly entered the national lexicon. By March 23, with the number of confirmed cases nearing five hundred, the government had prudently shut down all domestic and international flights and hardened its borders.

India is the world’s second most populous country. Yet it boasts one of the globe’s lowest levels of public expenditure on health care, just 1.3 percent of GDP, less than a fifth of what the European Union countries invest. Knowing this, the government recognized the virus as a grave, perhaps catastrophic, threat. Public health officials heroically pursued contact tracing. “Social distancing” and “self-isolation” rapidly entered the national lexicon. By March 23, with the number of confirmed cases nearing five hundred, the government had prudently shut down all domestic and international flights and hardened its borders. [From

[From  A month ago we sounded the alarm with

A month ago we sounded the alarm with  Eating garlic, taking a bath, and drinking hot water. These are three alleged “cures” that will not protect you from the coronavirus, but they have become so widely believed that the World Health Organization has launched a

Eating garlic, taking a bath, and drinking hot water. These are three alleged “cures” that will not protect you from the coronavirus, but they have become so widely believed that the World Health Organization has launched a  In a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility.

In a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility. It is historically unsurprising that, in the context of an emerging mass culture, nostalgia for older forms should express itself in their revival and imitation as high-art products. The adventure story was promoted into literature. A taste for this ‘canon’, from Stevenson to Kipling, from gaucho stories to Westerns, was formative for Borges, whose admiration for Conrad was well known. It is a mistake to consider Borges a modernist; rather, when he was awarded the Prix Formentor in 1961, marking his belated arrival on the world literary stage (along with Beckett, who shared the prize that year), it was a harbinger of the postmodern return to plot, to intricacy and intrigue, and away from the densities of poetic language. Conrad’s ‘postmodern’ reversion to plot was, however, combined with a different kind of modernist supplement, namely the work of style. Conrad dealt with his traditional raw material according to a stylistic strategy very different from Borges’s superposition of alternating plots and narrative paradoxes; yet the affinity betrays a deeper contradiction in the literary production process common to their respective historical moments.

It is historically unsurprising that, in the context of an emerging mass culture, nostalgia for older forms should express itself in their revival and imitation as high-art products. The adventure story was promoted into literature. A taste for this ‘canon’, from Stevenson to Kipling, from gaucho stories to Westerns, was formative for Borges, whose admiration for Conrad was well known. It is a mistake to consider Borges a modernist; rather, when he was awarded the Prix Formentor in 1961, marking his belated arrival on the world literary stage (along with Beckett, who shared the prize that year), it was a harbinger of the postmodern return to plot, to intricacy and intrigue, and away from the densities of poetic language. Conrad’s ‘postmodern’ reversion to plot was, however, combined with a different kind of modernist supplement, namely the work of style. Conrad dealt with his traditional raw material according to a stylistic strategy very different from Borges’s superposition of alternating plots and narrative paradoxes; yet the affinity betrays a deeper contradiction in the literary production process common to their respective historical moments. Covid 19 is a challenge to which we are all seeking to respond. Some major social upheavals lead to fundamental and progressive shifts, think for example of the way the AIDS crisis accelerated the fight for LGBT rights; while others, most obviously the global financial meltdown of 2008, fail to precipitate major reform despite causing immense hardship. Indeed, the widespread assumption on the left that the financial crisis would lead to a reaction against inequality and global finance was not only disappointed but confounded as the political momentum was, in many countries, seized by nationalist populism.

Covid 19 is a challenge to which we are all seeking to respond. Some major social upheavals lead to fundamental and progressive shifts, think for example of the way the AIDS crisis accelerated the fight for LGBT rights; while others, most obviously the global financial meltdown of 2008, fail to precipitate major reform despite causing immense hardship. Indeed, the widespread assumption on the left that the financial crisis would lead to a reaction against inequality and global finance was not only disappointed but confounded as the political momentum was, in many countries, seized by nationalist populism. Mark Denison began hunting for a drug to treat COVID-19 almost a decade before the contagion, driven by a novel coronavirus, devastated the world this year. Denison is not a prophet, but he is a virologist and an expert on the often deadly coronavirus family, members of which also caused the SARS outbreak in 2002 and the MERS eruption in 2012. It is a big viral group, and “we were pretty certain another one would soon emerge,” says Denison, who directs the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Mark Denison began hunting for a drug to treat COVID-19 almost a decade before the contagion, driven by a novel coronavirus, devastated the world this year. Denison is not a prophet, but he is a virologist and an expert on the often deadly coronavirus family, members of which also caused the SARS outbreak in 2002 and the MERS eruption in 2012. It is a big viral group, and “we were pretty certain another one would soon emerge,” says Denison, who directs the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.