Philip Ball in Prospect:

“Do me a favour, speed it up, speed it up.” That is what Donald Trump has been saying to the executives of pharmaceutical companies about their quest for a vaccine for the coronavirus. He has been told very clearly, not least by Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), that a vaccine will take at least a year to 18 months to develop. But, wrote H Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of Science in mid-March in an uncharacteristically furious outburst at the US president, “Apparently, Trump thought that simply repeating his request would change the outcome.”

“Do me a favour, speed it up, speed it up.” That is what Donald Trump has been saying to the executives of pharmaceutical companies about their quest for a vaccine for the coronavirus. He has been told very clearly, not least by Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), that a vaccine will take at least a year to 18 months to develop. But, wrote H Holden Thorp, editor-in-chief of Science in mid-March in an uncharacteristically furious outburst at the US president, “Apparently, Trump thought that simply repeating his request would change the outcome.”

The remark was, you might say, classic Don: petulant, heedless of inconvenient truths and spectacularly ignorant. (He reportedly crowned it with a botched offer of “large sums of money” to a German manufacturer to produce a putative vaccine exclusively for use in the United States.) But one can sense some of that same impatience in the air more broadly: why is there going to be no pharmaceutical magic bullet to get us through this crisis, but only one that will mop up afterwards?

Here, though, is the harsh truth: there will almost certainly be no vaccine ready to use against the Covid-19 virus until early 2021, and perhaps not before the summer of that year.

A typical timescale for developing a vaccine is 15-20 years—remember that there is still no vaccine against HIV today. The only way a coronavirus vaccine could be created as fast as this is by taking new approaches and judiciously cutting corners—for example, by taking some steps of the process that would normally be done sequentially and doing them simultaneously.

More here.

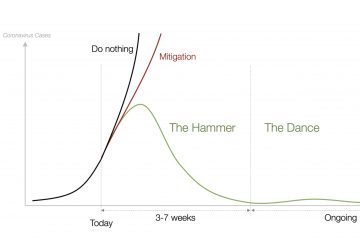

Summary of the article: Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have collapsed.

Summary of the article: Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have collapsed. How long is this going to last? As terrible as a pandemic would be, is averting it really worth a new Great Depression? What is the endgame?

How long is this going to last? As terrible as a pandemic would be, is averting it really worth a new Great Depression? What is the endgame? For an immeasurable public health disaster, Washington has come up with unheard of relief, about double what the federal government budgets for all spending in a whole year. And the case loads and death toll of the coronavirus keep rising, unevenly, unpredictably, and by far the worst in New York, city and state. Mark Blyth is our almost reflexive call: our political economist at Brown University, eagle-eyed and irreverent on those places where money and power mix and mingle and make rules for the world. He can sound like the noisiest know-it-all in a Glasgow pub, but people always say he has a gift for making sense where they hadn’t seen it.

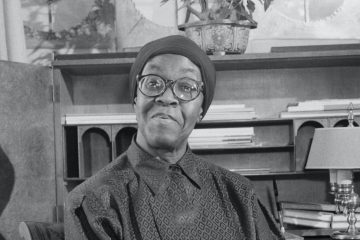

For an immeasurable public health disaster, Washington has come up with unheard of relief, about double what the federal government budgets for all spending in a whole year. And the case loads and death toll of the coronavirus keep rising, unevenly, unpredictably, and by far the worst in New York, city and state. Mark Blyth is our almost reflexive call: our political economist at Brown University, eagle-eyed and irreverent on those places where money and power mix and mingle and make rules for the world. He can sound like the noisiest know-it-all in a Glasgow pub, but people always say he has a gift for making sense where they hadn’t seen it. Gwendolyn Brooks grew up on Chicago’s South Side in a house her father bought shortly after the poet and her younger brother were born. Located at 4332 South Champlain, it was a comfortable home with a large front porch and backyard. The Brooks family was only the second black family on the block, but as the 1920s slid into the 1930s, African Americans began to move to the area in increasing numbers. Once a “Black Belt” was recognized, a series of discriminatory housing practices started: Chicago’s growing African American population was soon unofficially segregated. The narrow corridor of apartment buildings and houses along State Street could not hope to hold the explosion of skilled and unskilled workers who moved to the city during World War II; one solution was to chop existing houses and apartments into ever smaller units, called “kitchenettes.” These single rooms or series of small rooms, often rented at high profit by predatory landlords, housed entire families who shared kitchens, bathrooms, and much else. They were cramped microcosms of the circumscribed lives endured by most African Americans at the time.

Gwendolyn Brooks grew up on Chicago’s South Side in a house her father bought shortly after the poet and her younger brother were born. Located at 4332 South Champlain, it was a comfortable home with a large front porch and backyard. The Brooks family was only the second black family on the block, but as the 1920s slid into the 1930s, African Americans began to move to the area in increasing numbers. Once a “Black Belt” was recognized, a series of discriminatory housing practices started: Chicago’s growing African American population was soon unofficially segregated. The narrow corridor of apartment buildings and houses along State Street could not hope to hold the explosion of skilled and unskilled workers who moved to the city during World War II; one solution was to chop existing houses and apartments into ever smaller units, called “kitchenettes.” These single rooms or series of small rooms, often rented at high profit by predatory landlords, housed entire families who shared kitchens, bathrooms, and much else. They were cramped microcosms of the circumscribed lives endured by most African Americans at the time. These days, the singer-songwriter, who is forty-two, rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with Mercy. Five years ago, Apple stopped going to Largo, the Los Angeles venue where, since the late nineties, she’d regularly performed her thorny, emotionally revelatory songs. (Her song “Largo” still plays on the club’s Web site.) She’d cancelled her most recent tour, in 2012, when Janet, a pit bull she had adopted when she was twenty-two, was dying. Still, a lot can go on without leaving home. Apple’s new album, whose completion she’d been inching toward for years, was a tricky topic, and so, during the week that I visited, we cycled in and out of other subjects, among them her decision, a year earlier, to stop drinking; estrangements from old friends; and her memories of growing up, in Manhattan, as the youngest child in the “second family” of a married Broadway actor. Near the front door of Apple’s house stood a chalkboard on wheels, which was scrawled with the title of the upcoming album: “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.”

These days, the singer-songwriter, who is forty-two, rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with Mercy. Five years ago, Apple stopped going to Largo, the Los Angeles venue where, since the late nineties, she’d regularly performed her thorny, emotionally revelatory songs. (Her song “Largo” still plays on the club’s Web site.) She’d cancelled her most recent tour, in 2012, when Janet, a pit bull she had adopted when she was twenty-two, was dying. Still, a lot can go on without leaving home. Apple’s new album, whose completion she’d been inching toward for years, was a tricky topic, and so, during the week that I visited, we cycled in and out of other subjects, among them her decision, a year earlier, to stop drinking; estrangements from old friends; and her memories of growing up, in Manhattan, as the youngest child in the “second family” of a married Broadway actor. Near the front door of Apple’s house stood a chalkboard on wheels, which was scrawled with the title of the upcoming album: “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.” Huysmans reviewed the Salons of 1879-82 and the Independent Exhibitions of 1880-82 at considerable length. His articles, collected as L’Art moderne (1883), have never before been translated into English, probably because he is the least known of the writer-critics, and his French is often not straightforward. Robert Baldick, biographer of Huysmans (1955) and translator of his most famous novel, À Rebours, described his style as ‘one of the strangest literary idioms in existence’. Léon Bloy, a fellow writer and fellow Catholic, described it as ‘continually dragging Mother Image by the hair or the feet down the wormeaten staircase of terrified Syntax’. Brendan King, who has already translated most of Huysmans’s fiction, has produced an excellent version. Rarely can it have been such fun to read translated denunciations of so many forgotten French pictures. The edition also includes scores of small black and white illustrations, which can easily be Googled into colour.

Huysmans reviewed the Salons of 1879-82 and the Independent Exhibitions of 1880-82 at considerable length. His articles, collected as L’Art moderne (1883), have never before been translated into English, probably because he is the least known of the writer-critics, and his French is often not straightforward. Robert Baldick, biographer of Huysmans (1955) and translator of his most famous novel, À Rebours, described his style as ‘one of the strangest literary idioms in existence’. Léon Bloy, a fellow writer and fellow Catholic, described it as ‘continually dragging Mother Image by the hair or the feet down the wormeaten staircase of terrified Syntax’. Brendan King, who has already translated most of Huysmans’s fiction, has produced an excellent version. Rarely can it have been such fun to read translated denunciations of so many forgotten French pictures. The edition also includes scores of small black and white illustrations, which can easily be Googled into colour. Chances are, you’re hunkered down at home right now, as I am, worried about COVID-19 and coping by means of Instacart deliveries, Zoom chats, and Netflix movies, while avoiding others and the outside world. As shown by the experience in China1 and recent

Chances are, you’re hunkered down at home right now, as I am, worried about COVID-19 and coping by means of Instacart deliveries, Zoom chats, and Netflix movies, while avoiding others and the outside world. As shown by the experience in China1 and recent In the third week of February, as the

In the third week of February, as the  A global pandemic of this scale was inevitable. In recent years, hundreds of health experts have written books, white papers, and op-eds warning of the possibility. Bill Gates has been telling anyone who would listen, including the

A global pandemic of this scale was inevitable. In recent years, hundreds of health experts have written books, white papers, and op-eds warning of the possibility. Bill Gates has been telling anyone who would listen, including the  As the coronavirus outbreak in the US follows the same grim exponential growth path first displayed in Wuhan, China, before herculean measures were put in place to slow its spread there, America is waking up to the fact that it has almost no public capacity to deal with it.

As the coronavirus outbreak in the US follows the same grim exponential growth path first displayed in Wuhan, China, before herculean measures were put in place to slow its spread there, America is waking up to the fact that it has almost no public capacity to deal with it. The first big need is medical supplies, facilities and personnel. That is why we need to finance immediate domestic production of masks, oxygen tanks, ventilators and the construction and staffing of field hospitals, including the conversion of existing structures such as hotels, dormitories and stadiums, and the hiring and upgrading of staff.

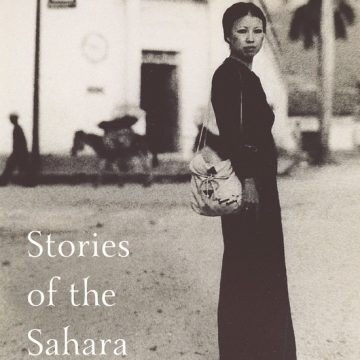

The first big need is medical supplies, facilities and personnel. That is why we need to finance immediate domestic production of masks, oxygen tanks, ventilators and the construction and staffing of field hospitals, including the conversion of existing structures such as hotels, dormitories and stadiums, and the hiring and upgrading of staff. As I read, I kept wondering why Sanmao’s persona was so magnetic. Is it simply because she was so unusual, out there in the vast and largely unpeopled desert, likely the only Taiwanese woman for miles around? Part of the draw of Stories of the Sahara is that it promises to satisfy our curiosity—what was she even doing there? But I couldn’t shake a sense of vertigo. I learned of Sanmao’s existence recently, through a teacher who had in turn learned about her from an article in the New York Times. And yet: “Of course we know who Sanmao is,” my parents told me over the phone. They grew up in Taiwan in the 1970s; they were in college when Sanmao began publishing her Saharan dispatches. One of my mom’s go-to karaoke songs is “The Olive Tree”—Sanmao wrote the lyrics. (“Don’t ask from where I have come / My home is far, far away.”) Who was this person, whose stories had traveled—across far-flung borders and multiple language barriers—from my parents’ lives into my own?

As I read, I kept wondering why Sanmao’s persona was so magnetic. Is it simply because she was so unusual, out there in the vast and largely unpeopled desert, likely the only Taiwanese woman for miles around? Part of the draw of Stories of the Sahara is that it promises to satisfy our curiosity—what was she even doing there? But I couldn’t shake a sense of vertigo. I learned of Sanmao’s existence recently, through a teacher who had in turn learned about her from an article in the New York Times. And yet: “Of course we know who Sanmao is,” my parents told me over the phone. They grew up in Taiwan in the 1970s; they were in college when Sanmao began publishing her Saharan dispatches. One of my mom’s go-to karaoke songs is “The Olive Tree”—Sanmao wrote the lyrics. (“Don’t ask from where I have come / My home is far, far away.”) Who was this person, whose stories had traveled—across far-flung borders and multiple language barriers—from my parents’ lives into my own? The Telegraph has branded the monkey-puzzle a “love-it-or-loathe-it tree.” Tony Kirkham, Head of the Arboretum, Gardens, and Horticultural Services at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew confirmed as much by phone: “Mhm. We call it the Marmite Tree.” Whether you go for the monkey-puzzle depends on how you feel about a Tim Burton cover of Dr. Seuss’s Truffula. Its spiraling leaves are as sharp as shivs, and some people effuse that the species is a “fantastic product.” “It’s one of those few trees that you can’t climb,” Kirkham noted. (You certainly cannot hug it.) He thinks the tree is grand, and when I mentioned monkey-puzzles to my friend Mitch Owens, AD’s decorative arts editor, Owens told me, “I adore them.” Others report back on the boughs as “savage curlicues,” “a nightmare to work in and around.” On a plant that can reach 160 feet and live 2,000 years, those branches hold forth like topiarian antenna, sending/receiving who knows what to/from who knows what galaxy.

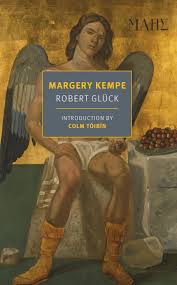

The Telegraph has branded the monkey-puzzle a “love-it-or-loathe-it tree.” Tony Kirkham, Head of the Arboretum, Gardens, and Horticultural Services at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew confirmed as much by phone: “Mhm. We call it the Marmite Tree.” Whether you go for the monkey-puzzle depends on how you feel about a Tim Burton cover of Dr. Seuss’s Truffula. Its spiraling leaves are as sharp as shivs, and some people effuse that the species is a “fantastic product.” “It’s one of those few trees that you can’t climb,” Kirkham noted. (You certainly cannot hug it.) He thinks the tree is grand, and when I mentioned monkey-puzzles to my friend Mitch Owens, AD’s decorative arts editor, Owens told me, “I adore them.” Others report back on the boughs as “savage curlicues,” “a nightmare to work in and around.” On a plant that can reach 160 feet and live 2,000 years, those branches hold forth like topiarian antenna, sending/receiving who knows what to/from who knows what galaxy. The cumulative strength of the New Narrative, which consisted of a core group of writers who took government-funded workshops run by Glück and the similarly under-sung Bruce Boone as well as some kindred, famous spirits far from Northern California—Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus—ensured that Glück’s name has remained in certain corners of the American literary edifice over the past few decades. Yet time and a shifting sensibility has relegated his own fiction to creaky personal libraries such as my own. I crack open original editions of Jack the Modernist and Margery Kempe and see the names of lost, idealistic imprints, SeaHorse and High Risk Books, which went down with the sinking ship of American publishing while larger houses bought space on the lifeboats. The paper trail of gay literature—put out by presses little and big—is inherently splotchy: so many people who had reason to remember died of AIDS.

The cumulative strength of the New Narrative, which consisted of a core group of writers who took government-funded workshops run by Glück and the similarly under-sung Bruce Boone as well as some kindred, famous spirits far from Northern California—Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus—ensured that Glück’s name has remained in certain corners of the American literary edifice over the past few decades. Yet time and a shifting sensibility has relegated his own fiction to creaky personal libraries such as my own. I crack open original editions of Jack the Modernist and Margery Kempe and see the names of lost, idealistic imprints, SeaHorse and High Risk Books, which went down with the sinking ship of American publishing while larger houses bought space on the lifeboats. The paper trail of gay literature—put out by presses little and big—is inherently splotchy: so many people who had reason to remember died of AIDS. It is not surprising to find Rusty Reno, editor of First Things,

It is not surprising to find Rusty Reno, editor of First Things,