by Charlie Huenemann

The living few, and frequent funerals then,

Proclaim’d thy wrath on this forsaken place;

And now those few who are return’d again,

Thy searching judgments to their dwellings trace.

– John Dryden, Annus Mirabilis: The Year of Wonders, 1666

This isn’t the first time universities have shut down from fear of pestilence. In 1665, “it pleased the Almighty God in his just severity to visit this towne of Cambridge with the plague of pestilence”, and Cambridge University was closed. Students were sent home, and all public gatherings were canceled. Some students arranged to meet with tutors over that time, but we can suspect that a good number of students simply went home, forgot about their studies entirely, prayed fervently, and followed whatever strategies they could to lessen the chance of death.

One student caught up in this nightmare was Isaac Newton. At the time, he had narrowly won a scholarship at Cambridge, which meant that he could continue his attendance; he could not otherwise afford it. It is a bit of a mystery just why Newton was afforded a scholarship, has he had pretty much left behind everything that his college valued and taught, and had embarked upon his own course of self-study. His focus was on developing a new mathematics that was more adequate to understanding motion, and in doing this he had few teachers who could help him (or even keep up with him). Over 1665, he lived, ate, breathed, and dreamed mathematics, and did little else in terms of our ordinary conceptions of living, eating, and sleeping.

A recollection he offered toward the end of his life gives us a sense of his activities at the time:

And the same year [1665] I began to think of gravity extending to the orb of the Moon & (having found out how to estimate the force with which a globe revolving within a sphere presses the surface of the sphere) Kepler’s rule of the periodic times of the planets being in sesquialterate proportion [3:2] of their distances from the center of their orbs, I deduced that the forces which keep the planets in their orbs must be reciprocally as the squares of their distance from the centers about which they revolve; & thereby compared the force requisite to keep the Moon in her orb with the force of gravity at the surface of the earth, & found them answer pretty nearly. All this was in the two plague years of 1665-1666. For in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention & minded Mathematics & Philosophy more than at any time since.

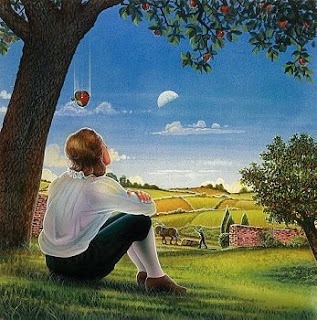

Arriving at these astonishing conclusions was certainly the result of years of intense study and persistence, but it is probably also true that a few months spent at home with nothing better to do gave Newton the open space he needed to chase his insights to their conclusion. These years have come to be called his anni mirabilis, or “miraculous years”, as they saw the fruition of his inquiries into the mathematics of nature. Or, if we don’t want to pay attention to all the tremendous effort and detailed work that went into them, we can think of them simply as the time when Newton went home, had an apple fall on his head, and thereby discovered gravity.

Now it might be a tad too much for our professors today to expect students to bring back new ideas that alter the course of human history upon their return to university. But we might well expect that students will learn a great deal when their studies are forcibly interrupted. For the business of schooling can be quite a lot of busyness. We like to believe that the endless parade of quizzes and assignments and tests and papers shape young minds into learned scholars, but in truth it is probably the time spent outside of the classroom where the most important elements of learning take place. This is especially true in our digital age, when young people have at their fingertips the greatest repository of knowledge and entertainment known to history.

Not that university classes don’t offer students anything: lots of content and technical know how are dumped into them, obviously. Furthermore, some professors serve as inspirations, or models of intellectual inquiry, and students carry with them those ideals long after they have forgotten exactly what they studied in their classes. But all humans also need time on their own to incorporate what they have learned into their perspective of the world. Students need to come across new events, and surprising conversations, and idle daydreams, so that all of the theories and big ideas find connection to parts of their own experience, and to their own self-generated thoughts. It’s like putting fertilizer near the roots of the plant: the plant then needs time and sunshine to assimilate the nutrients and allow them to become part of their lives.

So, as we try to escape our own pestilence, it is a good time to explore new ideas, and let our existing base of knowledge begin to grow meaningfully into our lives, connecting all those school lessons with the unexpected events of life beyond the classroom. If you’re lucky, an apple will fall on your head.

(Quoted passages taken from Richard Westfall, The Life of Isaac Newton, with minor alterations.)