by Katie Poore

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

During a recent visit to Paris, I squeezed through the crowded bookshelves of the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, a stone’s throw from Notre Dame, whose charred heights sat masked in scaffolding just across the Seine. It has become something of a Parisian tourist hotspot, mostly because of its association with our favorite Modernist expat writers, immortalized and gilded in a cosmopolitan, angsty, and glamorous mystique through the canonization of their works and, some might argue, the award-winning Woody Allen film Midnight in Paris.

Shakespeare and Company apparently played host and haven to such writers and legends as Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and James Joyce. In its upstairs rooms, an estimated 30,000 “Tumbleweeds” have slept on the book-lined benches that trace the rooms’ perimeters. A “Tumbleweed,” according to the Shakespeare and Company website, is a fleeting visitor, someone who, in the words of the bookstore’s founder George Whitman, “drift[s] in and out with the winds of chance,” much like the roaming thistles the word conjures. Shakespeare and Company just happens to have welcomed some of the most elite and canonized thistles the English-speaking world has known.

On my first visit to the store (yes, I went there twice), I was skeptical. It was a tourist trap, I reminded myself. Its paperbacks were marked up to the sometimes-outrageous price of 20 euros, and all because the store had harbored an impressive list of intellectual and literary powerhouses over the years.

But then I mounted the creaky stairs to the store’s second floor, and the chatter of the crowded room below receded into that particular silence unique to book-lined rooms. It was as if they absorbed the world, like the unsettling wool-covered walls I saw in a contemporary art exhibit at Centre Georges Pompidou. The books up here were old, with crackling spines and browned and yellowed pages and obscure titles. It was a room that felt better-preserved than its downstairs neighbor. People sat in silence in their own corners, reading.

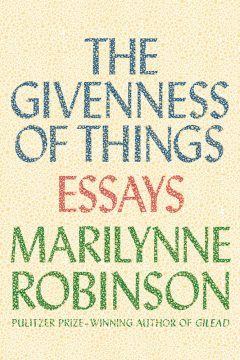

Needless to say, I spent too much money on a paperback that day. I came back the next day without my travel partners to retreat into that upstairs room, settling onto a Tumbleweed bench and cracking open Marilynne Robinson’s essay collection The Givenness of Things.

In a serendipitous occurrence, the first essay of the collection is titled “Humanism.” And what better place to read an essay defending humanism than the very setting in which some of our most iconic thinkers have grappled with questions of humanity? And, with the lingering ghosts of leaders of a literary movement largely and generally referred to as one expressing disillusionment and moral bewilderment, what better healing salve than a meditation on the unanswerable nature of a universe, and the sublime beauty that lies therein?

I mention this only because it is profoundly moving to understand human history as the evolution of thought and belief, as the reformulation of existential questions and the human effort to articulate, answer, and excavate them. And understanding Robinson’s “Humanism” as a response to, or a reorientation of, those questions asked by our beloved, tortured Modernists is, I think, a unifying sort of practice.

Indeed, Robinson speaks almost directly of the horrors of wartime violence often said to have inspired some of the questions investigated by Modernist writers. She says:

“If there were only one human query to be heard in the universe, and it was only the sort of thing we were always inclined to wonder about—Where did all this come from? or, Why could we never refrain from war?—we would hear in it a beauty that would overwhelm us. So frail a sound, so brave, so deeply inflected by the burden of thought, that we would ask, Whose voice is this? We would feel a barely tolerable loneliness, hers and ours. And if there were another hearer, not one of us, how starkly that hearer would apprehend what we are and were.”

I am compelled by this melancholy portrait of human uncertainty and loneliness. Rather than a tragic condition that plagues us, it is what makes us who we are: questioners, thinkers, lonely, but somehow universal. Alternately horrified and enraptured by the severity, violence, and wonder swirling incomprehensibly around us. Brave in the asking and burdened in the thought, seeking both identity and mystery, careening always towards those truths of existence, love, and violence we may never fully understand.

I like this contemporary philosophy, whether or not it is adopted widely or at all. It is a philosophy of question-asking, like that of the Modernists, but one equipped with the understanding of uncertainty as being sometimes exquisite, and of the world holding as much beauty as it does terror. We might be in the midst of an extraordinary and sometimes terrifying political (and environmental) climate, and we might feel lost and adrift, uncertain of meaning, uncertain of faith, uncertain of—well, most things, if we’ll just let ourselves admit it (something Robinson’s essay argues we are loathe to do, trading in the concept of mystery for a more empirical and scientific approach that insists everything must have an answer, and everything can be explained). But we are also in the midst of a great, inexplicable possibility, with a particular form of freedom that comes, if we’ll let it, from there being no true answers at all, but only postures toward the world: openness, curiosity, kindness, delight, melancholy, grief.

These sensations and postures constitute the human experience, as excruciating as they may sometimes be. Wondering is the human experience.

Modernism maintains an iron grip on Western thought’s cultural consciousness (or, at least on the cultural consciousness of English literature majors). Readers continue to be captivated by its fragmentation, its anguish and questions and bewilderment, its experimental nature and its rejection of classic literary forms. I love Modernism for this, too: for its vulnerability, its obvious pain, and the way it renders of that pain something beautiful, lasting, and as poignant now as it was a century ago. Many of these writers masterfully gave voice to an existential anguish that winds its way through every human mind on occasion.

In sitting in such close proximity to the lingering memory of these writers, thinkers, intellectuals, and human beings, the rain pounding against the window, a cat rubbing itself against my ankles, I had a sharp awareness of how earnest and urgent these questions still are, and how desperately we’d like an explanation or two offered up to us on occasion.

And I like to think of Marilynne Robinson’s voice added to the cacophony of doubt and questioning that may have filled those downstairs rooms whenever the Tumbleweeds weren’t all sleeping. She doesn’t ignore or diminish the weight of wondering, but she offers to Modernism, and to us, an antidote to its overwhelming painfulness. Perhaps loneliness can be beautiful, and confusion necessary. Perhaps we will never know ourselves, and perhaps that is how we are made to be.

But perhaps, too, the Modernists were already there. From their own uncertainty, they created art that is sharp and incisive and sometimes incomprehensible, but also bursting with the beauty that comes from the sheer humanity of feeling lost. They were, after all, the “Lost Generation.”

Perhaps, Robinson’s “Humanism” suggests, we’ve always located something ravishing in the unknowns. We just didn’t realize it.