by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was an odd fellow who eventually became someone else.

Born in 1832, he was the fourth of twelve children, and descended from a long line of English soldiers and priests all named Charles Dodgson. His parents were first cousins. He stuttered. A childhood fever left him deaf in one ear. As an adult he would suffer from migraines and epilepsy.

At age 12 he was sent away to school. He hated it. Still, he aced his classes and went on to Christ Church College in Oxford. He did not always apply himself, but nonetheless excelled at mathematics and eventually earned a teaching position. He remained at the school for the rest of his life.

Dodgson was conservative, stuffy, and shy. He was awed by aristocrats and sometimes snobbish to his social inferiors. He was mildly self-deprecating and earnestly religious. He had a reputation for being a very good charades player. He invented a number of gadgets, including a stamp collecting folder, a note taking tablet, a new type of money order, and a steering device for tricycles. He also created an early version of Scrabble. He liked little girls.

Dodgson enjoyed photographing and drawing nude children. He never married or had any children of his own. Whether his affection for pre-pubescent girls was sexual, or merely tied to Victorian notions of children representing innocence, is still debated. In the prime of his adulthood, one girl in particular caught his fancy: eleven year old Alice Liddell.

Dodgson spent much time with the Liddell family. A favorite activity was taking Alice and her two siblings out on a rowboat, where he would tell them stories. Alice so enjoyed the stories that she begged Charles to write them down. He presented her with a handwritten, illustrated collection in 1864. He called it Alice’s Adventures Underground.

Next, he brought the manuscript to a publisher. Several new titles were considered, including Alice among the Fairies and Alice’s Golden Hour. In 1865 it was published as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It was an immediate success. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, the odd man fascinated by numbers and other people’s children, had become celebrated author Lewis Carroll.

The book and its 1871 sequel, Through the Looking Glass, are at once simple tales of childhood fancy and stunningly complex pieces of literature. The stories are at turns straightforward and absurd. For example, Carroll occasionally employs what scholars call literary nonsense. Famous examples are two poems within the books, “Jabberwocky” and “The Hunting of the Snark.” They are largely gibberish and full of make believe words. Yet the books are so rich in word play, Victorian cultural references, parodies of other poems, mathematical concepts, and contemporary satire, that by 1960 The Annotated Alice was published, replete with hundreds of footnotes explaining this deceptively complex children’s story, because few adult readers could be expected to really “get it” without substantial help.

So simple and so complicated, Carroll’s two books about a small girl who went down the rabbit hole could be almost anything one wanted them to be. And so they became many things.

First the books began to change. In 1890, Carroll himself produced a shorter version for small children. Five years later, author Anna Richards imagined a new girl, also named Alice, who travels to Wonderland and has her own adventures. In 1897, a string of parody editions began appearing.

A stage production was developed as early as 1886. It featured musical pantomime. In 1903, Alice in Wonderland became a pioneering silent movie, with color tinting of the film and innovative special effects packed into its 12 minutes. After several more silent adaptations, the first talkie Alice premiered in movie houses in 1931. Betty Boop starred in a 1934 cartoon version called Betty in Blunderland. The story eventually served as an animated vehicle for Mickey Mouse, Popeye, The Three Stooges, Abbot and Costello, Hello Kitty, and the Care Bears among others; Walt Disney’s studio took its turn in 1951.

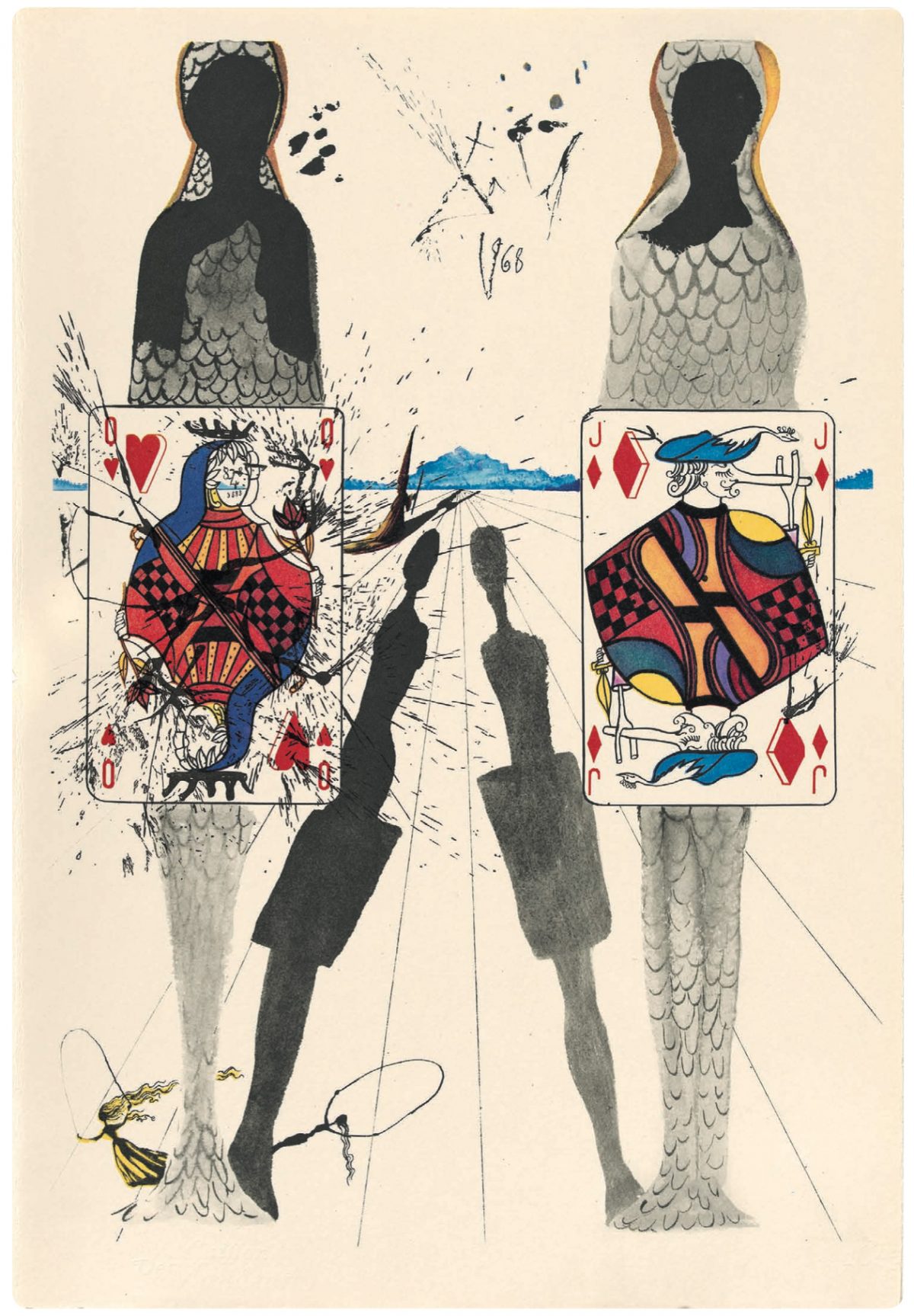

Alice in Wonderland first became a British TV show in 1937, many years before almost anyone had a television. The list of TV shows adapting the books in one way or another is exhaustive, ranging from the original Star Trek to Lost. Several Batman villains were drawn directly from Carroll’s roster of characters, including the Mad Hatter and Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee. In 1969, Salvador Dali made a dozen paintings based on the story. In 1976, the X-rated Alice in Wonderland: A Musical Porno appeared in theaters.

In the world of music, Alice became an orchestral piece (1914), a choral work (1942), a symphony (1969), two ballets (both in 2010) and several operas (1973, 1995, 2007). But none of those clung to me. Rather, it was a short song, written in 1965 by a woman who was in the process of reinventing herself, and who soon thereafter reinterpreted her own song with a new band that also kept changing and remaking itself.

Grace Barnett Wing was born outside Chicago in 1939 and grew up in Palo Alto, California. After a year of college in New York City and another in Miami, she dropped out, married an aspiring film maker, and settled in San Francisco. She spent three years working as a model in a department store, and now went by her married name: Grace Slick.

During this period she also began writing songs. In 1965, Grace Slick, her husband Jerry, her brother-in-law Darby, and another friend teamed up to form a musical group. They called themselves The Great Society, a mocking reference to President Lyndon Johnson’s domestic political program. By the end of the year they were a popular local act.

It was around this time that Grace Slick wrote a song about Alice called “White Rabbit.” The Great Society was at the forefront of San Francisco’s emerging psychedelic scene, and Slick’s lyrics rendered imagery from Lewis Carroll’s books into a cipher for hallucinogenic drug use.

One pill makes you larger and one pill makes you small

And the ones that mother gives you don’t do anything at all

Go Ask Alice when she’s 10 feet tall

Around Slick’s lyrics and chords, The Great Society painted a musical tableau that reflected psychedelia’s ethos of open mindedness, drug experimentation, and sometimes naive overtures to proto-multicutluralism. The piece opens with an extended instrumental jam that conjures images of Middle Eastern snake charmers before Slick starts singing about “a hookah-smoking caterpillar” who has summoned you to take this trip.

Listen to a live Great Society recording from 1966 and you find that the lyrics and melody are already sorted out. But the singing is different. This is not yet the famous Grace Slick. This a the mid-20s, first marriage, model-turned-singer who had yet to pursue music as a full time career, and who is still learning how to use her voice. Her signature vibrato is there, but it is not fully formed. She’s occasionally off key.

As The Great Society played club dates around town, they sometimes found themselves on the same bill as another band quickly bubbling up from San Francisco’s vibrant music scene. They were called Jefferson Airplane, and they too had a female singer.

Signe Toly Anderson was already an accomplished folk and jazz singer when she signed on as a founding member of Jefferson Airplane in 1965. She sang on their debut album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off. However, when she became pregnant by her husband (Jerry Anderson, who was one of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters), she quite reasonably decided that life on the road with a drug addled rock band was no way to raise a kid. So she quit.

The band needed a replacement. They wanted a woman with a deep, powerful voice like Anderson. The lead singer of The Great Society now became the lead singer of Jefferson Airplane. And she brought her songs with her.

Grace Slick’s new band worked over “White Rabbit” before recording it for their second album, Surrealistic Pillow. They slowed down the tempo, giving it a more meditative feeling The musical introduction was shortened substantially and re-arranged to recall Maurice Ravel’s “Bolero,” which had originally inspired Slick while writing the song. The whole thing was now barely two and a half minutes, its centerpiece the rising crescendo of Grace Slick’s vocals, which culminated in a soaring finale. And this time she didn’t miss any notes.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson had become Lewis Carroll. Alice Liddell had become the Alice of Carroll’s fantasy world. Stories told on a rowboat had become world famous books. Alice in Wonderland had become many things, including parodies, plays, paintings and pornography. And in the hands of Grace Wing, who herself had become Grace Slick, it became an early hippie jam for The Great Society, the breakthrough single for Jefferson Airplane, and an anthem of the 1960s counterculture.

*

CODA (noun): 1. a concluding musical passage typically forming an addition to the basic structure; 2. a concluding event, remark, or section. A coda on the circuitous and comical, tangled and tragic evolution of Jefferson Airplane can be found here.