by Mary Hrovat

I think it was in the 1980s that I first saw t-shirts showing a drawing of a spiral galaxy with an arrow indicating “You are here.” They were amusing, and the image provides a bit of cosmic context. You may be here, looking at this screen, with your to-do list and personal problems and worries about the world, but you’re also here in the Orion arm of the Milky Way, about 25,000 light years from the center, in this solar system, on this planet.

One way to capture the most local part of your cosmic context is the 3D solar simulator at The Sky Live, which shows a simulated snapshot of the locations of all the planets relative to the sun at this moment. You can zoom in and out and add asteroids, near-Earth objects, and comets. You can also animate the simulation. At one week per second, you get a pretty good view of the tight circling of the inner planets, but the outer planets move at a very sedate pace. At one year per second, the inner planets move too quickly to follow easily, but the outer planets sweep along briskly.

Of course, you can also observe the solar system from the inside. One great way to broaden your horizons is to go out in the evening to see what other planets in the solar system are visible and to watch them moving along in their orbits over the weeks and months. There are a number of guides to what you can see on a clear night. Sky & Telescope provides a weekly update that tells you which planets will be visible, what phase the moon is in, and whether there will be any events such as eclipses or meteor showers. Space.com offers a monthly summary that covers a somewhat broader range of things to look for in the night sky, and EarthSky describes what you can see in the sky tonight.

In addition, space is not an unchanging backdrop but a place with its own weather (sort of) and events. Spaceweather.com posts news stories about solar activity, aurorae, meteor showers, fireball observations, and more. The sidebar on the left shows current data and images.

###

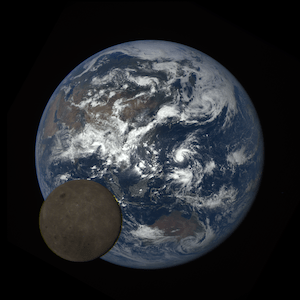

The Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) spacecraft was built to observe Earth and provide alerts and forecasts for solar activity that will affect us. Until late June 2019, multiple images of the sunlit side of Earth taken by the EPIC instrument were posted most days. Since then, however, DSCOVR has been in safe mode as it awaits a software patch that will return it to service.

I’ve missed these views of weather systems moving across the planet, the slow changes of the seasons as the northern and southern hemispheres tip toward the camera in turn, and rarer spectacles such as the shadow of the moon moving across the face of Earth during a solar eclipse. Seeing these things every day placed me in a larger context.

The images of Earth should be available again after the patch is applied (perhaps by March 2020). In the meanwhile, you can view any of the images recorded from July 2015 through June 27, 2019 or check out the galleries of particularly interesting images. DSCOVR is far enough from Earth that it sometimes sees the moon passing in front of Earth, for example, on July 5, 2016, as shown in the image above (there’s a gallery of still images and also a video of this event).

It can also be mind-expanding to look at the weather going on across the entire planet, rather than just the local conditions or even the weather in your country. EarthWindMap shows the entire globe; the default view shows global winds, but a menu (click “earth” at lower left) allows you to select a wide variety of different overlays (one at a time) and different projections. MeteoEarth has fewer options (which include temperature, winds, atmospheric pressure, cloud cover, and precipitation) but allows you to view more than one overlay at a time.

###

There are also far more living things surrounding us than we usually think about. Watching the living world going about its daily activities can be an excellent antidote to immersion in human problems.

Explore.org links to wildlife webcams (some seasonal) that cover a multitude of environments and animals worldwide, including wildlife in Africa, aquariums, birds, and bears. The US National Park Service also hosts various wildlife webcams that offer views (again, some seasonal) of bears, eagles, and the ocean, and Wildlife Forever links to a selection of wildlife cameras, with a focus on birds. The bird cams at The Cornell Lab’s All About Birds site let you watch birds going about their lives, many in the US but some in other parts of the world. You can see highlights on the lab’s YouTube channel.

###

All of these resources are good for when you must engage with the online world; if you’re in a cubicle staring at a screen for much of your work day, they offer a respite. In many cases, they provide experiences that would otherwise be inaccessible. However, they can’t replace the experience of simply observing your natural surroundings, whatever they may be: watching the clouds cross the sky, seeing rain or snow or fog come and go, and, even in the city, observing birds and other animals.

Long periods of time spent watching the natural world, with no particular goal, can amount to a contemplative or meditative practice. The only instruction or training is “Pay attention, and don’t stop watching just because nothing obviously exciting is happening.”

If you sit under a starry sky long enough that you can see the positions of the stars appear to shift, you can almost persuade yourself that you feel Earth turning. It’s worth sometimes watching an entire sunset through all the permutations of color and light as the sun disappears and the darkness rises up the eastern sky. Or walking or sitting anywhere—a park, a back yard, a porch—and attending to the sky, the light, the wind, the shape of the land and any plants that cover it, and any animals that happen into view. Sometimes I think this is one of the best and most important uses of consciousness: to observe and appreciate our natural setting, and then to love it.

###

The image is courtesy of NASA’s EPIC team.

I am indebted to Patrick Alexander for his observation that “sitting and watching things that are not immediately interesting for long periods of time is a rewarding activity.”

You can see more of my work at maryhrovat.com.