by Eric J. Weiner

The allure of fresh and true ideas, of free speculation, of artistic vigor, of cultural styles, of intelligence suffused by feeling, and feeling given fiber and outline by intelligence, has not come, and can hardly come, we see now, while our reigning philosophy is an instrumental one. —Randolph Bourne

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

By contrast, writing to learn re-conceptualizes our relationship to writing from measurable outcomes to critical/creative processes. It moves the epistemological needle from instrumentality to exploration, innovation, imagination, and discovery. Writing to learn supports the development of what Randolph Bourne (1917) called “poetic vision.” Having poetic vision diverts our “creative intelligence” away from “the machinery of life” and redirects our “creative desires” toward enhancing the quality of life. “It is the creative desire,” Bourne writes, “…that we shall need if we are ever to fly” (from Twilight of Idols).

Several decades after Bourne’s warning about the limitations of John Dewey’s pragmatic rationalizations of war, Julia Cameron published The Artist’s Way, a book that claims to teach people how to develop and deepen their poetic visions and creative desires. Her book and workshops are a lifeline toward a more creative and meaningful life for millions of people. Although The Artists’s Way is by all measure a practical book, it avoids instrumentality. Rather than a serious study/guide toward creativity, academic researchers across the social sciences often dismiss her work–if they acknowledge it at all–as new age spiritualism wrapped in the language of self-help and healing. Indeed, healing and renewal form the backbone of Cameron’s ideas about creative desire and poetic vision rather than the science of cognition, neurology, society, culture, genetics, or biology.

For her fans and acolytes, she has created a practice of creativity that is holistic, organic, and empowering. Creativity is ontological and, according to Cameron, we can reclaim who we were or reach beyond who we have become through creative activities and disciplined practices. We are born divergent thinkers but throughout our lives, due to our experiences with negative forms of socialization, disciplinary structures of reward and punishment, and various kinds of physical and emotional trauma, we become less creative, less able to call upon our imaginations to free our minds and bodies from various repressive states. Although her book precedes third-wave cognitive behavioral therapy by at least ten years, there is a strong suggestion of it in her approach to psychic healing and creativity. She claims that the practices she describes in her book and workshops have the power to heal trauma, rewrite destructive and diminishing circuits of thought and action, and release our creative desires and poetic visions from the prison of negative experience and diminishing habits of mind/body in which they’ve been caged.

I am not one of her acolytes or fans, although I am not a naysayer either. I apply the adage “take what you need and leave the rest” to Cameron’s work. One of the practices that form the foundation of The Artist’s Way and that I find valuable is called “Morning Pages.” These are to be written each morning before checking email, social media, texts or even getting out of bed. They are intended to purge the mind/body of thoughts and feelings that can potentially muddy the day’s work. From Cameron:

Morning Pages are three pages of longhand, stream of consciousness writing, done first thing in the morning. There is no wrong way to do Morning Pages–they are not high art. They are not even “writing.” They are about anything and everything that crosses your mind– and they are for your eyes only. Morning Pages provoke, clarify, comfort, cajole, prioritize and synchronize the day at hand. Do not over-think Morning Pages: just put three pages of anything on the page…and then do three more pages tomorrow. https://juliacameronlive.com/basic-tools/morning-pages/

Since being introduced to The Artist’s Way twenty-years ago, I have been intrigued by the practice of Morning Pages. I wish I could say I did them consistently over the last twenty years, but I have not. When I have done them, I feel the potential power in the practice. Not the power to heal trauma and the like (although I certainly am not going to argue with over five million readers as to the efficacy of the routine and I acknowledge that maybe I would feel the healing power of the practice if I did them as directed), but what I do sense is its relationship to the production of new knowledges.

The articulation between epistemology and creativity is one that I have been exploring throughout my academic career and artistic life in part due to the impact of Cameron’s work. In retrospect, I think this relationship has fascinated me for as long as I have been putting pen-to-paper, brush-to-canvas, linoleum-to-ink, sharpie-to-fabric, eye-to-lens, and hands-to-clay. Although I was not necessarily conscious of their arrival or how they might impact my thoughts and actions, there seems to always have been new knowledges arising from my artistic endeavors. Inversely, in the absence of creative practices, the dearth of new knowledges is consciously and deeply felt. Inertia of the spirit, idleness of hands, and dullness of thoughts replace the vitality that comes from creating and leaves me struggling to get out of my own way. This has led me to think about how writing can function as a praxis of learning, sustenance, and renewal. The kind of writing that interests me does not fall easily into the categories of fiction, non-fiction, expository, analytical, theoretical, directional, informative, poetic, philosophical, or autobiographical, yet it might, on some level, tap into or skirt around the edges of all of these.

Writing to learn refers to a divergent process of exploring new knowledges and different ways of knowing through the creative practice of writing what we don’t know. I am not speaking about writing a research paper or journalistic article and, as a consequence of the investigation the writer of the essay learned about her subject. This would be an example of researching to learn while the writing becomes a way to record what the researcher, through some method of inquiry and/or analyses, has learned. Writing in this context is primarily about the final product and although this is an important stage in the writing process for many genres of writing, when we write to learn we shouldn’t be concerned with the final product or showing an audience what we have learned and/or already know; it is focused instead on how through writing we can come to learn more and differently than we did before we started writing.

Writing to learn, as I am imagining it, is a divergent social practice fueled by a lovely cocktail of curiosity, imagination, experience, and ignorance. For my purposes, there are two kinds of ignorance that most matter. The first kind of ignorance can be characterized as a refusal to learn. When reason, experience, scientific research, rigorous theory, and historical knowledge are not enough to educate a person to the wrongness or limitations of her ideas then this is a refusal to learn; it is a form of ignorance dependent on willful power, tribalism, and arrogance.

The second kind of ignorance, by contrast, describes a state of “not knowing.” This state of not knowing has a couple different registers. One register is when we know what we don’t know but don’t know how to find the answers we need. The other is when we don’t know what we don’t know. In both instances, writing to learn can help bring us closer to a state of knowing. I am most interested however in how writing to learn can plumb the depths of the second register of ignorance; that is, how it can reveal what we don’t know we don’t know. This practice of imagination and curiosity might never get beyond the register of coming to know what we don’t know and is therefore not an end in itself. It can’t replace other forms of knowledge production. At some point, it might be helpful to actually learn about the thing we discovered we didn’t know we didn’t know. But this process of knowing is not linear and as such our movements in and out of knowledge and ignorance don’t have clearly defined beginnings and ends.

The “How” of Writing to Learn

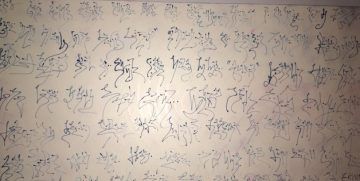

Just as there is no real method nor quantifiable measure for this kind of writing, there isn’t a template that one can follow either. Unlike Cameron’s “Morning Pages,” there is an object of curiosity about which the writer writes. The writer doesn’t just write about anything but rather has a subject however loosely imagined that she is grappling to understand more deeply. She continues to read about the subject from multiple perspectives as she writes through her confusion and disorientation. She writes what is essentially a twisting web of tenuous relations. Through writing, she connects to new knowledges and feelings by short-circuiting the habituated mind/body from the normalizing conditions of everyday life. Words soon appear from the depths of the unconscious, floating upon the page of consciousness to be read and re-read as though someone else had written them.

There are strategies that can assist in helping writers move through what can be for some a strange and frustrating process. From dialogical notebooks to multi-sensory prompts, writers can use these tools, as Maxine Greene might have said, to release their authorial imaginations. People who were taught first the mechanics of writing (i.e., how to write) and then schooled to think about writing as a tool for recording and communicating, have the most trouble grasping the practice of writing to learn. From texting to research papers to fiction, they have been taught that writing is a way to show someone what you are feeling, thinking or have learned. At most, some were asked to explain, through writing, how they came to know what they know. As such, it is a practice situated at the level of description and measured by standards of outcome that have been standardized. Writing to learn, by contrast, is valuable because it’s not about a final product, but rather is a process of self- and social discovery, creation, and reflective analysis. It’s essentially writing about what you don’t know in order to discover what you didn’t know you didn’t know.

There are strategies that can assist in helping writers move through what can be for some a strange and frustrating process. From dialogical notebooks to multi-sensory prompts, writers can use these tools, as Maxine Greene might have said, to release their authorial imaginations. People who were taught first the mechanics of writing (i.e., how to write) and then schooled to think about writing as a tool for recording and communicating, have the most trouble grasping the practice of writing to learn. From texting to research papers to fiction, they have been taught that writing is a way to show someone what you are feeling, thinking or have learned. At most, some were asked to explain, through writing, how they came to know what they know. As such, it is a practice situated at the level of description and measured by standards of outcome that have been standardized. Writing to learn, by contrast, is valuable because it’s not about a final product, but rather is a process of self- and social discovery, creation, and reflective analysis. It’s essentially writing about what you don’t know in order to discover what you didn’t know you didn’t know.

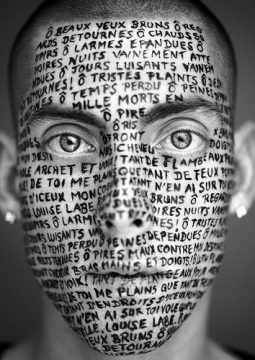

I encourage people to use prompts to start this process of writing to learn. A prompt can come from a quote from another person about something the writer finds interesting or provocative. It can be a visual, auditory, tactile, or multi-sensory prompt. In any case, the writer begins writing as though in conversation with the prompt. Then in a free-form, stream of consciousness style, unconstrained by convention, the writer begins to unleash her imagination onto the page. Thoughts don’t have to be at first coherent but they should be authentic, grounded in real emotion, experiences (imagined or real), and memory. One idea flows or crashes into the next. Superficial thoughts can lead to deeper levels of feelings. These feelings are unfamiliar and require a retreat to the surface, only to be sucked down even deeper as one continues to explore the unfamiliar and the strange.  This kind of writing to learn can be confusing, terrifying, heartbreaking, joyous, soulful, affirming, fracturing, and disruptive. It’s like hiking through an unknown forest where the trails crisscross and switch-back, rise up and then descend rapidly. You lose your footing often, sometimes landing painfully on your back, looking upward at the underbelly of a canopy of trees, or a kaleidoscope of dissolving clouds, or a squall of stars so brilliant and multitudinous that you sink into the soft machine of time becoming invisible to yourself. This kind of invisibility allows you, as if for the first time, to see.

This kind of writing to learn can be confusing, terrifying, heartbreaking, joyous, soulful, affirming, fracturing, and disruptive. It’s like hiking through an unknown forest where the trails crisscross and switch-back, rise up and then descend rapidly. You lose your footing often, sometimes landing painfully on your back, looking upward at the underbelly of a canopy of trees, or a kaleidoscope of dissolving clouds, or a squall of stars so brilliant and multitudinous that you sink into the soft machine of time becoming invisible to yourself. This kind of invisibility allows you, as if for the first time, to see.

At some point, you get up a little bruised and maybe a bit embarrassed but intent on moving, not forward per se, but in whatever direction this path you are now on leads. This is an important aspect to remember because when we write to learn we are being led by an “invisible hand,” one that pushes us to explore paths of knowledge that we wouldn’t even be aware of before we started writing. The invisible hand can be gentle, guiding the writer by the arm into the unknown. Or it can be brutish, gripping the writer’s neck until she feels like she’s going to lose consciousness; it presses her forward, down, or pushes her back. But the result is the same–new pathways of knowledge are revealed and traveled, explored and experienced.

At some point, deep into the hike, the trail will inevitably become overgrown and the writer must use her machete to cut through the thickening brush. The going is painfully slow. Muscles ache. She chops and slices, blisters ripping open across the soft flesh of her mind. As Michel Foucault understood, “Knowledge is not made for understanding; it is made for cutting.” And there is a blissful pleasure in the cutting. The light from the sun slices through the detangle of branches and leaves. The trail starts to open and a more worn path intersects with the one the writer is on. She takes that path not knowing where it will lead, but does sense that the crossing of borders demarcates being from being more.

But writing to learn also might mean becoming less than we are. It is a purging practice; that is, to know more or differently through writing we must also experience what it is to unlearn, to decolonize our minds and bodies, denaturalize habituated thoughts and actions, and cut into the flesh of ignorance. As we mark the page with our thoughts and feelings, some doors open, while others close. Through this kind of writing we can begin to purge knowledges from deep in our psychic architecture thereby rewriting the power they have to condition the shape and direction of our ideas and actions. By engaging in the divergent practice of writing to learn, we can travel beyond what we know, fuel our creative desires, and realize the potential of our poetic vision to liberate us from the rationalization of instrumental thinking.