Kenan Malik in Pandaemonium:

‘A poem is not a lecture; a story is not an argument. The way poems and stories work on our minds is not by logic, but by their capacity to enchant, to excite, to move, to inspire.’ So writes Philip Pullman in his introduction to John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

‘A poem is not a lecture; a story is not an argument. The way poems and stories work on our minds is not by logic, but by their capacity to enchant, to excite, to move, to inspire.’ So writes Philip Pullman in his introduction to John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

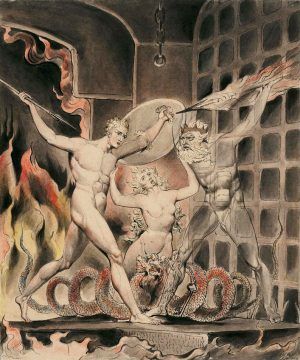

Milton’s epic remains one of the greatest retellings of the Christian story, a work that has mesmerised writers through the generations from William Blake to Pullman himself. Pullman’s His Dark Materials, the striking BBC adaptation of which ended its first series last week, reworks Paradise Lost, turning its moral message on its head. Milton’s poem tells the story of the Fall; of Satan’s banishment from heaven for leading a rebellion against God and of his revenge in corrupting Adam and Eve and hence all humans, by tempting them to eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

In His Dark Materials, knowledge is seen not as corrupting but as liberatory; it’s the desire to keep certain knowledge forbidden that corrupts. Deeper down, though, what links the two works is a common reverence for human dignity and a recognition of the complexity, both of humans and of storytelling.

Milton wrote Paradise Lost to ‘justify the ways of God to men’. The star of the work, however, is not God but Satan, fanatical and malevolent, yet heroic in a most tragic way. As Blake observed of Milton, he is “of the devil’s party without knowing it”.

More here.