by Joan Harvey

The radio music is smooth now, sentimental, semi-classic in the popular vein…music something like a golden bell, promising that tomorrow will be better. Jazz, good jazz, tells no such lies. —Charles Wright, The Messenger

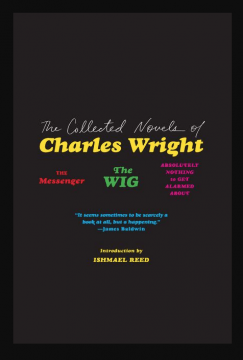

Recently, in an independent bookstore in a city I was visiting, one of the books I randomly scooped up to weigh down my luggage on the way home was The Collected Novels of Charles Wright, with an introduction by Ishmael Reed. The confusing thing was, had I heard of him? It seemed to me that of course I had, but there is a famous American poet named Charles Wright and this is not that man. There was also of course Richard Wright; the first novel in this collection is dedicated in part to him. There’s Charles White, the artist, whose work I happened to see on this same trip. But the Charles Wright of these novels is Charles Stevenson Wright (1932-2008). I later looked this collection up on Amazon. There are zero reader reviews of this edition. The last copyright before this was 1993. And yet he’s back in print, or still in print; there are editions of the novels separately. Very little has been written about him. Yet Wright’s writing felt familiar, as if he were an old friend.

The collection contains Wright’s three novels. The first, The Messenger, is from 1963, The Wig from 1966, and Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About from 1973. The Wig is satirical and fictional; Reed cites it as an influence. Some think it is a better book than the other two, which are mostly made of vignettes of Wright’s direct experience. I prefer the more autobiographical books that bookend the satire. In Absolutely Nothing Wright mentions having a drink with Langston Hughes in the Cedar Tavern just before Hughes died. Wright remembers Hughes saying, “The Wig disturbed me, and it’s a pity you can’t write another one like it. But don’t. Write another little book like The Messenger” (278). Although The Wig is a scathing and often brilliant satire, I think Hughes was right.

Wright writes about what he sees, what he experiences, how he lives. If he needs bennies and weed and a lot of booze to get through the day he says so, without castigating himself or making it good either. He is complicated, life is complicated, race is complicated. And yet his writing doesn’t feel complicated. It’s full of humor, metaphor, strong images, but no varnish. In order to know the world better he risks all kinds of experiences. When young he is eager to fight in Korea just to see more of the world. There is mention of time he has spent in Morocco and Mexico. In Absolutely Nothing he lives down on the Bowery and describes how young white kids jackroll the winos and black queens regularly without violence and the more hardened black criminals fleece the old white winos after they get their checks. He goes to fancy parties; he gets high with bums. He’s understanding about other people and revealing of himself. His descriptions show the falsity and hierarchy and constant striving that make up New York.

That afternoon, as I walked through the concourse of the RCA building, sneezing and reading Lawrence Durrell, dead drunk from the explosion of his words, I suddenly looked up and encountered the long face of Steven Rockefeller. He seemed startled. Doesn’t he think poor people read? (7)

It’s the nature of Wright’s writing, the vivid, accurate directness of it, that allows me to feel I’ve met most of these characters, the hustlers, the queens, the hustling queens, the liberal white people, the junkies, the Wall Street guys. As if I know Wright’s New York with its cheap flophouse hotels, but then, as now, changing: “Big new office and apartment buildings, bright new street lights, the cops clamping down like the great purge” (39).

Wright’s somewhat detached curiosity leads him into other people’s lives. He was bisexual, so not part only of either the straight or queer worlds. He was a country boy in New York, a well-read and well-connected man living among hustlers and junkies and winos. And because he’s a very light-skinned black man he’s also “a A minority within a minority” (88). An outsider’s outsider, which makes him a good writer. When young he’s very attractive. Men and women want to take him home. Often he goes. He observes their furniture, their kinks. It’s not about his desires or his ego, but what he sees. “Still, Third Avenue has a little seedy, fashionable charm and sometimes I wander over, step through all that rich dog shit which peppers the sidewalk like a mosaic and peer into antique shops, knowing that some freaklina will accost me. I’ll be picked up for ten-plus-drinks, or by a Vassar-type of girl who will want to discuss jazz” (39).

His writing is vivid and often funny. A modern Danish chair looks like a “miniature ski lift.” “Depression multiplies like cockroaches.” “He looked like an angelic little boy who had been kicked out of his orphanage for failing to take part in group masturbation.” “I remained worldly, indifferent, like Marcello Mastroianni.” “Despite an abundance of expensive flowering plants, the inner room had the serene masculinity of a GI sleeping bag.”

Sometimes because he’s black he’s reduced by others to something exotic. A friend takes him into “the rich world of queendom. ‘Writer? How interesting!’ They knew slews of writers. I need to get away to the Cape, or Fire Island…. I don’t look like a messenger. (What does a messenger look like?) They’re all round me, talking in their prissy, cultured voices, and I’m thinking Jesus, Jesus, the latest hunk of meat to be tossed into the arena” (15).

It’s the question that Wright asks—“What does a messenger look like?”—that sticks. He shows with deep, quick insight our presumptions about other people. Later, after sex, he writes, “It was an experience, nothing more. And if I felt like it, I’d do it again. It was as simple as that” (15). This is where Wright is different from most writers, perhaps more honest. Life doesn’t have to be good, doesn’t have to be dramatic or tragic to be something to take in. When it isn’t great it isn’t necessarily something to weep about or hide from. He’s observant, judgmental, but also open. Open to himself, to the world, to experience that’s both destructive and informative. He loves his grandma. Sometimes he hangs out with a precocious little girl who lives in his building and they joke and have tea and cookies and ride the Staten Island Ferry. In his later life Wright lived in a friend’s home and the friend said Wright was a second father to his kids. He has many sides. Sometimes he’s suffering from a woman he likes who prefers a rich doctor. Sometimes he’s turning tricks for money. People want him to do things and often he does. But he never panders. At times he gets in trouble, and he doesn’t move up in society like he should. Yet he’s not a tragic figure. He knows who he is. Later, although he didn’t publish more books, and drank too much, Reed says, “I have photos of Charles Wright taken at a dinner in his honor at a downtown restaurant. He didn’t seem to me that he had ‘vanished’ in ‘despair’” (xix).

The novels are also a devastating portrait of American racism. Wright grew up, well-behaved, motivated, in a small Missouri town. He describes, when young, applying for a busboy job. He’s told the job has been taken but the ad continues for another week. He goes back to ask about the job again. “‘Boy, can’t you get it through your thick skull, we don’t hire niggers.’ It was like being slapped hard across the face or dashed with a bucket of ice water” (53).

Later, age 16, walking home from a job in a bowling alley where he’s called coon and nigger, he detours through a white neighborhood because he likes the old Victorian houses. He’s picked up by the police. Because he tells them he’s on the track team they make him run around and around the station faster and faster until he’s sweating and exhausted and his legs give out.

‘You sure can run fast,’ another policeman said, handing me my wallet.

‘Never saw a nigger who couldn’t,’ another policeman reflected.

‘Yeah,’ the gray-haired policeman agreed. ‘But stay across the tracks. Do you hear me?’” (87).

The second novel, The Wig, the book that influenced Reed, is more satirical. The premise of The Wig is that a hair relaxer will get the protagonist, Lester Jefferson, a new life. “Carefully I read the directions. The red, white, and gold label guarantees that the user can go deep-sea diving, emerge from the water, and shake his head triumphantly like any white boy” (139). The hair is a success, soft and shining, but moving up in the world is not. Lester applies for jobs: “First, I had to fill out an application and take a six week’s course in the art of being human, in the art of being white. The fee for the course would be one-five-o” (167). He and a washed-up actor go into a recording studio, where they’re welcomed because they look right. “Two groovy colored studs. You’ve got everything in your favor” (188). But it turns out that, in spite of racial expectations, they can’t actually sing. He cadges money from his Uncle Tom godfather to spend on a girl he likes. The godfather keeps a hopeful count of all the reported deaths of white people, and they drink to spring and to death. But leaving the fancy apartment where Tom works, Lester runs into a modern runaway slave and gives him all the money that he’s just obtained. He then strangles and skins some giant rats to give to the girl for a fur coat, and ends up with a job crawling around town on his hands and knees in a giant white chicken costume.

The Wig contains scathing passages, like this about a friend: “He was slowly dying. Time and time again the doctors had explained to him that Negroes did not have bleeding ulcers nor did they need sleeping pills. American Negroes, they explained, were free as birds and animals in a rich green forest. Childlike creatures, their minds ran the gamut from Yes Sir to No Sir. There was simply no occasion for ulcers” (154).

In the third novel, Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, we’re back to more closely autobiographical writing. Wright is older, he’s working as a dishwasher, life is harder. He’s living on the Bowery; there are riots in Brownsville in Brooklyn. He goes to more parties and writes for The Village Voice. He skewers upper middle class black life: “Of course they give money to black causes and buy the Black Panther newspaper… All of them agree that New York’s finest pigs are ‘terrible. Just terrible.’ And like skimming fat from milk, they are as bourgeois as a Republican Vice President. Y’all hear me? Riot all over the goddamn city, but don’t bomb Macy’s, Gimbels, or Bloomingdale’s. Do not open a drug-addict center within five hundred miles of Tanglewood” (285).

The writing is also funny, with great juxtapositions:

“But there’s a war going on. We’re at war with whitey,” the poet said dramatically.

I looked at A.X. He nodded gravely. Was he thinking of his Irish doorman, who said, ‘Good evening, Mr. Coombs’?

“I wanna dance.” Hillary pouted. “I wanna dance with my dress up over my head” (287).

Wright corresponds with Norman Mailer. He says of Mailer, whose writing he admires, “Naturally his comments on civil rights and blacks interested the dishwasher.” But then he quotes what Mailer has written about himself: “. . . he was getting tired of Negroes and their rights…he was so heartily sick listening to the tyranny of soul music, so bored with Negroes triumphantly late for appointments…” and on and on, until Mailer’s confession that “he must have become in some secret part of his flesh a closet republican” (380-381). Wright tries to give Mailer the benefit of the doubt, but clearly this is depressing.

Wright sees how racism has made life as an ordinary individual impossible for him:

That rude bitch of sweet dreams, Mama Nightmare, has hung me like a polka dot, like a black Star of David, below the fascist, Germanic clouds of South Africa, U.S.A.

She has been with me for a very long time, even before I could read and write. The guys at Smitty’s gas station in Boonville, Missouri, called me dago. Aged five, I knew dago was not nigger. But they have remained stepbrothers to this day, forming an uncomfortable army with kike, Polack, poor white trash. But I had nigger, Negro, coon, black, colored, monkey, shit-colored bastard, yellow bastard…Was I ever Charles Stevenson Wright?”(289).

In Absolutely Nothing Wright uses the word “skulled” a lot. It’s hard not to think that the combination of racism, his refusal to pander and play the game, and his sensitive but underrated talent have led him into the need for a kind of permanent numbing that he isn’t going to disguise. It’s a more painful book than the other two to read.

Perhaps I should follow the advice that I’ve been given over the years: buy a tweed suit or whatever type of suit is fashionable at the moment and make the literary-cocktail la ronde. You know, even blacks do it.

And your father or my father might do it. I’ll never do it: But I’ll knock down more wine and go out on the fifth-floor fire escape of the Kenton Hotel” (373).

It’s a dark picture. Wright has been faulted for not overcoming the lure of alcohol and writing more. But not everyone can play the game. And on the other side, not everyone can tell us what it’s like to wash dishes in fancy white resorts. What it’s like to know and admire Norman Mailer and then be hit in the gut by his racism. Wright ends this section with “Thinking of all I’ve done and not done. Thinking and feeling a terrible loss” (373).

There’s a startling episode in The Messenger. Troy and Susan, white friends whom the narrator had introduced to each other, have married and had a child and have been living abroad. They call him up; they’re back in New York; they want to visit him right away. The narrator, who has shown us in other scenes his fondness for children, picks up their three-year-old son, and jokes with him. “‘Nigger,’ Skipper said in a clear, small voice” (15). The parents are embarrassed and apologetic. But the scene shows the racism always so close to the surface, displaced from the nice-seeming parents onto the small boy.

Later he’s with the same couple at a party. “Troy and Susan were leaving for an intellectual gathering in the Village. They can’t quite forgive me because their child once called me ‘Nigger,’ and to conceal the fact have been especially warm and friendly ever since” (129). There is so much psychological knowledge in these few lines.

This edition of Wright’s novels was reissued in 2019. While so far it hasn’t had much attention, the quality of his writing has assured that at least he’s in print. Baldwin praised The Messenger. Reed says, “Their basic difference is that Baldwin, in the words of Chester Himes, was ‘ambitious, while every time Success knocked on Wright’s door, he wasn’t home’” (xi). But there is success in Wright’s unflinching look at himself and America, and in these three slim novels that linger so strongly in the mind.

Wright, Charles. The Collected Novels of Charles Wright. New York, Harper Perennial, 2019.