by Rafaël Newman

And the children of the moon / Were like a fork shoved on a spoon

Hedwig and the Angry Inch

1.

1.

The goddess Demeter, having received the Earth as her domain in the post-Titanic dispensation that followed the parricidal murder of her father Kronos, had mated with her brother Zeus, lord of the Sky, and borne a daughter, Persephone, whom she adored. Their brother Hades, meanwhile, whose dominion was the Underworld, was as yet without a wife; and his gaze now fell on his niece, Persephone. With his brother Zeus’s connivance he kidnapped the object of his desire, whereupon her mother Demeter subsided into melancholy and perpetual winter was visited upon the Earth: until an agreement was reached, to forestall the death of all creatures, and Persephone was allowed to return to the surface, on condition that she not have eaten anything while below. But Hades had in fact persuaded her to swallow six pomegranate seeds; and thus she was condemned to return to the Underworld henceforth for six months of the year, during which period her mother, Demeter, mourned for her, and the Earth was cast into darkness, and cold.

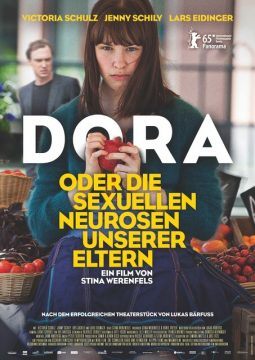

My daughter saw it immediately. We had just spent a week in Istanbul, and our daily dose of nar suyu, fresh-squeezed pomegranate juice, was still a pleasant sense memory; so she was primed to spot the plump fruit on the poster in the lobby of the cinema where we had gone to see Dora, oder die sexuellen Neurosen unserer Eltern (“Dora, or The Sexual Neuroses of Our Parents”). This was the pomegranate that had afforded her so much pleasure in Asia Minor, and which is reputed to have been the snake’s gift to Eve, and thus hers to Adam, in the Garden of Eden. This particular pomegranate, however, was part of a story of natural origins from a different cultural tradition, but was to prove no less my fruit of knowledge that evening as I began to decipher Stina Werenfels’ retelling of a myth central to western culture. A myth about fertility, and death, and love, and sex. And food.

Because Werenfels’ Dora is, among other things, about eating. About edible gifts: the ice cream enjoyed by Dora’s romantically-minded colleagues, Max and Sara, on a park bench; the treats prepared by her mother, Kristin, a professional caterer; the fruit sold, and given away, by Dora and her boss at their market stand. In equal measure it is also about food (and other pleasures, oral or otherwise) forsaken, lost or withheld: the birthday cake that falls on Dora’s shoe at her party, occasioning a tantrum; the kiss she seeks from her father, Felix, and is refused; and of course that pomegranate, which Dora offers the saturnine object of her affections, and which rolls away, unaccepted, unnoticed, in the midst of an act that initiates the film’s central trauma.

Werenfels’ Dora begins, in fact, with an oral dose denied: by Kristin, Dora’s mother, who will take a more commanding, and significant, role as protagonist in Werenfels’ treatment of the eponymous play than she does in Lukas Bärfuss’s work. By deciding to halt the course of medication Dora has been on for much of her life, against an unspecified host of evidently debilitating symptoms, Kristin plans to grant her daughter the womanhood that has been held in check by pills, and opens the gates to a burgeoning sexual curiosity that will lead Dora to the encounter with the man who declines her gift of a pomegranate, and consummates their inchoate relationship on the floor of a public washroom in the underground U-Bahn station.

Werenfels takes her pomegranate from Bärfuss’s play, where, however, it is offered in a less weighted, more ironic bit of stage business by Dora’s boss, the market stall tender, to the “elegant gentleman” (feiner Herr) who will eventually take a nefarious interest in Dora. By transferring the bestowal of that symbolic fruit from her patron to Dora itself, Werenfels grants the young woman agency in her own sexual awakening, even as the director insists, by staging Dora’s seduction of the elegant gentleman in a subterranean toilet, on the Stygian character of their liaison. And she points her audience more deliberately than Bärfuss does towards this mythic subtext, the legend of the maiden ravished by a sinister older man, ransomed by her mother, and condemned thereafter to divide her time between a supernal, feminine realm of light and warmth, and an infernal, masculine world of sexual servitude.

In Werenfels’ retelling, the withholding of food that is to permit the maiden’s return from that underworld is performed prophylactically, rather than post hoc, by her mother, and with a reverse, if unspoken, intent: Kristin wants to give her daughter the gift of womanly experience, which implicitly includes the sexual pleasure that the mother herself, visiting a fertility clinic with Felix in a bid to become pregnant with a second, “normal” child, is currently unable to enjoy. Werenfels’ Dora is taken off her regimen of pills so that she can undertake her journey to the (Under)world of sexual pleasure, while the mythical Persephone must refrain from indulging in pomegranate seeds so that she can return from her sexual captivity.

In response to her mother’s controlling munificence, however, Werenfels’ Dora takes matters into her own hands: she courts Peter, the “elegant gentleman” – in the film a sleekly sensuous, occasionally sentimental abuser – by following him down the stairs and into a public facility in the underground, where she “seduces” him by urinating in his presence and presenting him with a gift of a pomegranate from her market stall. When he rapes her on the floor of the washroom, and the proffered fruit rolls away, unacknowledged, into a corner of the squalid space, Werenfels seems at first to be staging a cloying allegory of the pathos of deflowerment: until the camera, trained on Dora’s face, makes it clear that, without the benefit of romantic inoculation, she is assimilating the contemptuous, impersonal assault as pleasure.

For Werenfels’ work is also a profound exploration of the nature and social structure of sexual pleasure, as well as of the limits of parental love and control. Despite its reception as a virtually documentary treatment of a “taboo” topic in the director’s native Switzerland, where reviewers were scandalized by its improperly scintillating depiction of sexual acts involving the differently abled, Dora is not interested in real existing mental or physical conditions at all. Although Werenfels’ realist treatment of Bärfuss’s surrealism (as enacted in his unconventional stage directions and dryly Dürrenmattian monologues) suggests documentary intention, to misread Dora as a sociological rather than a symbolic document is akin to receiving Lolita as a TED talk for pedophiles rather than as an allegory of the relationship between the Old World and the New.

Dora’s “condition”, which is cursorily sketched at best, functions instead as the switch that allows her mother to turn on her daughter’s sensuality and access to womanly, human pleasure, heretofore muffled, and to open for her a supposedly beneficial Pandora’s Box of delights. The trauma that this work of art ostensibly enacts – the erotic lives of the neurodiverse, and their special vulnerability to exploitation by predators in the neurotypical world – and which proved so difficult for the Swiss film establishment to assimilate (and finance), thus turns out to be of a more elemental variety: the pre-programmed failure of the parent’s emancipatory gesture. Indeed, the true trauma of Werenfels’ Dora is its frank avowal of the structural impossibility of imposing freedom on another individual. The mother’s bestowal of the “gift” of womanhood on her daughter, and the former’s subsequent reduction to the status of an anguished onlooker, as the latter realizes the potential of that womanhood, and constructs for herself an autonomous, “perverse” sexuality: these are an enactment of the scandalous truth of maternity, which creates two out of one, an unequal dyad in which the “originary” half is exceeded and eventually abandoned by the other, its product and the ungrateful beneficiary of its loving, selfish, neurotic “gift” of autonomy.

2.

Aristophanes, the fifth-century Athenian playwright caricatured in Plato’s dialogue on the nature of love known as the “Symposium”, develops in that dialogue a myth of the origin of desire. Humankind, Aristophanes says, was originally trisexual in nature: man, woman, and a combination of the two, or “androgyne”. Furthermore, each individual human, regardless of sex, was double: that is, possessed of four hands and four feet, a head with two faces, four ears, two sets of genitalia et cetera. But in their organic completeness, their circular self-sufficiency, these ur-creatures were filled with overweening pride and arrogance, and made an attempt on the gods in their home on Mount Olympus; whereupon these latter, led by Zeus, decided to split them in two, to lessen the threat. And thus ever after, the two halves of each primordial being – man/man, woman/woman, woman/man – have sought out their complement, so as to be restored to their original state of wholeness and bliss.

Released, now, from the unitary bliss of the womb – twice over – by a mother who has re-borne her into a world of stimulation, of colour and decision, of autocratically imposed “freedom”, Dora craves nothing so much as oneness. Her mother has effected a cleavage, by separating her from the medication that had kept her cocooned in blissful unknowing, a sundering which replays her original extrusion from uterine symbiosis, a head birth from which Dora springs fully formed, and capable of desire, coitus, pleasure, and melancholy. The rest of the film will follow her through the various stations of her quest for (re)union, for the healing of the wound inflicted on her by Kristin, who is the arbiter of her affective destiny, the superego which enjoins her to enjoy. Small wonder, then, that one of those stations, in both Bärfuss’s savage template and Werenfels’ more decently Freudian version, will be an attempted incursion into the dyad that forged her.

For Dora will stage her own primal scene, bursting into her parents’ bedroom as they are practicing their grimly procreative sex. In an early version of the screenplay, Werenfels had in fact intended to open the film with this scene, in which a still medicated Dora merely stumbles, unaware, upon her parents in flagrante. The episode is then repeated (and thus filmed) in the sequence detailing Dora’s experiences following her weaning from medication, presumably to highlight the pathos of the newly individuated young woman’s search for congress, and underscoring its no longer aleatory quality by having Dora notice her father’s erect member with interest: which of course lends extra piquancy to the daughter’s joining her parents in bed post-interruption. She will also attempt to practice on her father the passionate embrace she has just witnessed between her similarly “handicapped” colleagues, Max and Sara, on a park bench, untrammelled by the incest taboo and thus all the more painfully rebuffed by her appalled father.

Dora speaks in unwittingly Aristophanic terms about her own desire: rebuked by Max for putting her hand on his crotch during the embrace, and told by her father that Max and Sara are permitted to engage in this behavior weil sie ein Paar sind – “because they are a couple” – Dora exclaims: Ich will auch ein Paar sein – “I want to be a couple too!” And later, as Kristin attempts to console her after she has been subjected to verbal abuse at the market – called a Mongo, or “mongoloid” – by telling her that she is not behindert (“handicapped”), merely anders (“other” or “different”), Dora wails, Ich will nicht anders sein! (“I don’t want to be other/different!”). But of course her protest comes too late, since otherness is inscribed in the very experience of birth and individuation: quite literally, in Dora’s case, since her family name is “Anderson”.

At the same time, Dora is hopefully initiating herself into the repertoire of cultural gender (makeup, “feminine” clothing, jewelry) and of sexual stimulation (masturbation in the bath), and her secondary sexual characteristics are becoming increasingly evident and culturally significant, initially to her father, and ultimately to potential exogamous objects, such as Peter, Werenfels’ version of Bärfuss’s feiner Herr. Their first encounter, at the market stand where Dora works, segues seamlessly into coerced sexual congress. Dora has followed Peter to the pharmacy where he has business and from there into the underground, where she presents him with the pomegranate, urinates in his presence, and is raped by him. In the ensuing scene she is interrogated by the police and examined by a gynecologist, to whom she responds, when asked to render an account of the incident: Scheiden-Pimmelchen ist schön! (“Vagina-willy is lovely”). She has constructed this portmanteau term for sexual congress as a gloss in response to her mother’s pedantically correct explanation of human (heterosexual) erotic behavior, as a means to rendering the abstract process more vivid; now she has been subjected to an anatomically, if not sentimentally, equivalent version on her person, and transfers the neologism reflexively from the domesticated nuclear-family template to her own anomalous experience. She thus bestows upon her abusive, loveless treatment at the hands of a stranger the status of a culturally acceptable event in the history of human affective relations, while assigning to it a name that foregrounds the mechanical nature of the encounter even as it signals her recognition of a healing of the wound she has suffered as a result of the cleavage from her original oneness, whether amniotic or pharmaceutical.

Dora unchained is thus a desiring-machine, scandalously celebrating that raw bliss in which pleasure and pain are commingled and which is meant to be foregone in the interest of a culturally productive enjoyment. And in distinction to the hollowed existence of her parents, who have foresworn bliss in the name of other, more socially acceptable, less outrageous principles, Dora is entirely replete – in the blissful harness of an autonomous, solipsistic oneness with the other half of her Scheiden-Pimmelchen machine: a spherical, originary being once again, part of a whole, a round body adorned by and filled with glittering, germinal, jewel-like eggs and seed (of which her gaudy navel piercing is merely the outward sign: the crown of the pomegranate).

3.

Orpheus, the son of the god Apollo, was a musician of such power and expertise that he could charm any living creature with his song. When his beloved Eurydice died and descended to the Underworld, however, he was overwhelmed with grief and resolved to harrow hell to retrieve her. In the Kingdom of the Dead he was able to charm its beastly denizens with his music and bend even the god of the realm to his will, and Hades agreed to let him take Eurydice back with him to the world of the living above, on condition he not turn to look at her until they had cleared the exit. But Orpheus forgot his pledge when he had reached the light, and turned, and looked back at Eurydice, who was still emerging from the shadows: and lost her a second time.

Ultimately, of course, Dora will be abandoned by Peter “at the altar” to an inadvertent, un-erotic experience of oneness with another: to her pregnancy, which, if not entirely desired by Dora, she has nevertheless not colluded in preventing. And as Dora attempts (symbolically and unsuccessfully) to perform a late-term abortion on herself, by mutilating her pierced navel, sign of her own nativity and site of original cleavage, only to give birth in the same public lavatory in which she was raped by Peter, Kristin, despondent at the loss of her daughter to the dangerous bliss of a rapist’s “affections” (or rather, his violent, fickle, cowardly whims) and despairing of a marriage leeched of bliss by a joyless regimen of chemically enhanced copulation, seeks solace in a drug-assisted descent into an erotic Underworld of her own.

Refused attendance upon Dora in her travails, Kristin, who is catering a louche party thrown by a sexy acquaintance, accepts from the latter a consolatory gift of recreational drugs, swallows the proffered pill and embarks on a nocturnal odyssey: into one of Berlin’s notorious underground discos, staged in what might be an abandoned (albeit glamorously enhanced) U-Bahn station, where she engages in a watery orgy notably involving snakes and a tattooed lover, and heralded by the appearance of a naked pregnant woman in a fur hat, solemnly processing through the entrance to an inner sanctum.

The oneiric quality of the sequence, which features slow-motion camera work, ecstatic dancing, and Kristin’s fascinated observation of herself as lovemaking doppelganger with multiple partners, marks it as otherworldly, and of course the character is under the influence of some manner of euphoric. But the animal motif and reddish glow of the orgy scene also serve to make of Kristin’s carousing an Orphic catabasis (the viewer recalls the infernal cigar smoke that attends the equivalent scene in Black Orpheus): an artful descent into the nether realm in quest of a lost love object, reunion with which, however, is sabotaged by the seeker’s scopophilic dependence on visual reassurance. In Kristin’s case, of course, we do not know as the film ends – for this is its final scene – whether she will be able to transport her lost bliss, now rediscovered, back into the upper world. What we are left with is a vision of her naked body, stretched out like an odalisque on a banquette in an alcove set into the curving, tiled wall of a caldarium, and arrayed between niches containing a bed and a vanity; and a close-up of her face, relaxed now, finally, after the stress and anguish that have beset her features for much of the film, glowing with post-coital satisfaction. Her gaze meets ours as she looks frankly into the camera, acknowledging the viewer’s scopophilia even as she indulges her own, at the risk of losing once again that scandalous bliss, the impossibility of an immortal pleasure, which must in any case be renounced in the name of art.

Envoi

The Titan Prometheus had challenged the gods, allied himself with humanity, and paid a grisly forfeit; and as part of the vengeance wreaked on overweening humankind by those jealous deities, Pandora was created and bestowed upon the suffering Titan’s brother, Epimetheus. For as soon as she had been accepted into Epimetheus’s home, Pandora opened the jar she had been given by the gods, and released into the world of humans, still luxuriating in their Golden Age, all of the ills that have plagued them ever since, as Toil, and Disease, and Pain, and Death. And when all of these evils had escaped, all that was left in the jar was Hope.

The film’s final sequence, in which Kristin experiences the twin escapist transports of chemical intoxication and anonymous sex, is intercut with scenes of Dora post-partum, seen in close-up as she nurses an apparently healthy newborn at her unblemished breast. (She had last been glimpsed in the act of mutilating her own belly and prostrating herself on the floor of a public washroom.) The “gift” that is Dora – the matryoshka doll that she had become; the disappointing plaything of her parents, and of Peter; the jeweled vessel bearing within it the manifold ruin of its recipients – has been opened, and this newfound oneness, too, another iteration of the mother-daughter dyad that has structured the film, cleft in twain: even as her own mother reclines, languidly solitary, within a jeweled vessel of her own.

Solitary, and yet framed as the central panel of a triptych, a painterly feast for the gratification of the viewer, who is frankly acknowledged by Kristin’s eye contact. And at this moment of visual pleasure we hear a single word, uttered off-screen, the film’s final line: Mama. Dora intrudes even here, in Kristin’s bastion of womanly self-sufficiency: but she intrudes only as a category; or rather, as a distant nomothete, consigning Kristin to the symbolic category of “mother,” from which she has for the moment escaped.

And of course, her high will subside, her orgasmic glow will dim, her duties as mother – and grandmother! – will presumably interpellate her anew upon her ascent to the world above. But she has also (at least temporarily) found her place within that triad which at once prefigures, mimics, perfects, and exceeds the dyadic relationship of mother and child, lover and beloved, two halves of one originary whole. She has acceded to her role in the triangular relationship that subtends the aesthetic (in this case cinematic) experience: author – character – consumer. And the ratio of the film’s title to its subtitle is at last made plain, translated from the rhetorical to the algebraic: “Dora” – her parents’ Pandora, their gift of troubles – is revealed in apposition to, as the equivalent of, “the sexual neuroses” of those parents, the most patent symptom of that self-harming disease of narcissism, obsessive-compulsive disorder and a creed of genetics-as-destiny that afflicts and drives all reproductive humans.

In the aftermath of her attempt to square the circle of enforced freedom, of the proclamation of liberty and its revocation in the bonds of morality, of the (re)production of originary oneness that circumvents bliss in the name of science, Kristin will be left with the evils of a hangover, a memory of adultery, and the pain of having been refused access to her child by that child herself – but also with the compensatory promise of an aesthetic future.

And indeed, without drugs, without sex, without children: what else is there to hope for?

DORA ODER DIE SEXUELLEN NEUROSEN UNSERER ELTERN from Dschoint Ventschr Filmproduktion on Vimeo.