Margaret Wardlaw in Guernica:

Madison was never expected to live this long. The doctors had told her parents she would probably die at birth. Surprising everyone but her mother, she seized and trembled, and refused to suckle—but she didn’t die. Madison never learned to walk. Her four limbs were spastic. She remained small for her age, and she never learned to speak, not even to say Mama or milk, or no. But she saw and experienced many things beyond seizures, infections, breathing and feeding tubes; beyond Christmases and Easters and birthdays, and the everyday intimacies of childhood. She was her mother’s joy, and knew a fierce and indelible love, breathed over her in a nightly vigil. It imbued Madison with the quiet beauty of a survivor. Whatever trials she endured, there was a sense that she was lit from inside by something sacred.

Madison was never expected to live this long. The doctors had told her parents she would probably die at birth. Surprising everyone but her mother, she seized and trembled, and refused to suckle—but she didn’t die. Madison never learned to walk. Her four limbs were spastic. She remained small for her age, and she never learned to speak, not even to say Mama or milk, or no. But she saw and experienced many things beyond seizures, infections, breathing and feeding tubes; beyond Christmases and Easters and birthdays, and the everyday intimacies of childhood. She was her mother’s joy, and knew a fierce and indelible love, breathed over her in a nightly vigil. It imbued Madison with the quiet beauty of a survivor. Whatever trials she endured, there was a sense that she was lit from inside by something sacred.

Still, there were the hospitals. The familiar scene, where doctors told Madison’s mother that her daughter would not survive, played out over and over as the little girl got older. She would get sick—her pulse quickening, fever rising, skin becoming clammy—and then she would get very sick, convulsing with seizures, rapid breath shaking her thin frame. But then, just when she was so sick that everyone thought it would be the final sickness, she would get just a little better. Each time this happened, Madison’s mother, living in ambiguity since her daughter’s birth, would trust the doctors a little less. By the time she got to the hospital where I was a doctor, Madison was almost eighteen. This time she really was dying. Sent to our regional referral center by her well-meaning rural physicians who thought they had nothing left to offer, Madison was barely responsive. The sliding-glass door of her hospital room framed a scene that was, at first glance, distinctly modern. State-of-the-art monitors spewed data, and machines pumped tube feeds and broad-spectrum antibiotics into her body. But Madison’s mother, keeping watch by the bed, her face bent over the curled body of her daughter, was a timeless image of suffering, like a stoic pieta. Except that she bore no trace of the placid, limpid resignation the Holy Mother always seemed to wear. She was unbelieving, and angry.

Your daughter is dying, the doctors at our hospital told Madison’s mother. Doctors always say that, she responded.

More here.

I often think that my obsession with Ezra Pound’s poetry was due to his well-known formula “DICHTEN = CONDENSARE” (dichten means “to write poetry” but also “to seal” or “to tighten” in German) or to those chestnuts from “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste,” such as “use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation [of the thing],” all of which was appealing because I was well practiced in reducing these programs to the bare minimum while still achieving their effects. No one wants to play a video game that is too slow or too easy or ends up in an uncontrolled loop (an early version of the spinning pizza of death) because of sloppy coding. One pleasure of programming is reducing many lines of unwieldy code to a few elegant ones, maybe as a function that can be called upon repeatedly. In some ways, I think this is a central pleasure in writing poetry as well—cutting lines, swapping out dull words for lively ones, interjecting a tonal shift that renders some strictly explanatory lines superfluous, and so forth—all while seeing the effect increase as the poem gets smaller.

I often think that my obsession with Ezra Pound’s poetry was due to his well-known formula “DICHTEN = CONDENSARE” (dichten means “to write poetry” but also “to seal” or “to tighten” in German) or to those chestnuts from “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste,” such as “use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation [of the thing],” all of which was appealing because I was well practiced in reducing these programs to the bare minimum while still achieving their effects. No one wants to play a video game that is too slow or too easy or ends up in an uncontrolled loop (an early version of the spinning pizza of death) because of sloppy coding. One pleasure of programming is reducing many lines of unwieldy code to a few elegant ones, maybe as a function that can be called upon repeatedly. In some ways, I think this is a central pleasure in writing poetry as well—cutting lines, swapping out dull words for lively ones, interjecting a tonal shift that renders some strictly explanatory lines superfluous, and so forth—all while seeing the effect increase as the poem gets smaller.

Unlike Armstrong or Cukor, who stay true to Alcott’s timeline, Gerwig begins in the middle of the narrative, depicting the second half of the book while weaving in scenes drawn from the first. We open on the March sisters in their late teens or early twenties. The women in question are no longer very little, and the Civil War that cast a shadow over their youth has ended. We find the eldest, Meg, searching for contentment in her new life as the wife of a poor tutor (James Norton). Played by Emma Watson, she is the picture of grace if not always the voice, her Yankee accent at times on the brink. Tomboyish Jo—Ronan, offering a perfect compromise between Ryder’s timidity and Hepburn’s ham—is in New York avoiding an unwanted marriage proposal from her best friend, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), and chasing after her dream of becoming a writer. Amy (Florence Pugh), the bratty baby, is in Europe to hone her painting skills and find a society husband. Only sweet, sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen) remains at home, though she will soon depart on an adventure of a more permanent kind, as she learns to accept her slowly impending death, the consequence of childhood scarlet fever. As she says of her fate in one of Alcott’s most poetic lines, delivered with solemn elegance by Scanlen, who makes the most of Beth’s limited part: “It’s like the tide . . . when it turns, it goes slowly, but it can’t be stopped.”

Unlike Armstrong or Cukor, who stay true to Alcott’s timeline, Gerwig begins in the middle of the narrative, depicting the second half of the book while weaving in scenes drawn from the first. We open on the March sisters in their late teens or early twenties. The women in question are no longer very little, and the Civil War that cast a shadow over their youth has ended. We find the eldest, Meg, searching for contentment in her new life as the wife of a poor tutor (James Norton). Played by Emma Watson, she is the picture of grace if not always the voice, her Yankee accent at times on the brink. Tomboyish Jo—Ronan, offering a perfect compromise between Ryder’s timidity and Hepburn’s ham—is in New York avoiding an unwanted marriage proposal from her best friend, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet), and chasing after her dream of becoming a writer. Amy (Florence Pugh), the bratty baby, is in Europe to hone her painting skills and find a society husband. Only sweet, sickly Beth (Eliza Scanlen) remains at home, though she will soon depart on an adventure of a more permanent kind, as she learns to accept her slowly impending death, the consequence of childhood scarlet fever. As she says of her fate in one of Alcott’s most poetic lines, delivered with solemn elegance by Scanlen, who makes the most of Beth’s limited part: “It’s like the tide . . . when it turns, it goes slowly, but it can’t be stopped.” Jugaad is a hack, a hustle, a fix. It’s a lot from a little, the best with what you’ve got—which is likely not much, if you need jugaad. A “very DU word,” a Delhi University grad once explained to me, and I thought about how college students as a rule and around the world turn nothing into something (e.g., instant noodles).

Jugaad is a hack, a hustle, a fix. It’s a lot from a little, the best with what you’ve got—which is likely not much, if you need jugaad. A “very DU word,” a Delhi University grad once explained to me, and I thought about how college students as a rule and around the world turn nothing into something (e.g., instant noodles). A facility that saw 53,000 emergency room visits per year disappeared from Philadelphia this summer with the prolonged and still-unfinished closure of Hahnemann University Hospital. The 496-bed hospital employed 2,700 people and saw 17,000 admissions in 2017, its last year under the management of the Tenet Healthcare Corporation. Tenet, one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital conglomerates, owned ninety-six hospitals and nearly 500 outpatient centers in the United States that year. Not all of them turned a profit. Hahnemann, for example, booked $790 million in revenue in 2017, $115 million short of breaking even. So Tenet embarked on an international restructuring program, liquidating seventeen low-margin hospitals in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Philadelphia, Tenet sold Hahnemann to Joel Freedman, a man from Los Angeles who sat on the advisory board of the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics (his name has since been removed from the center’s website) and managed an investment fund, Paladin Capital, with interests in “the world’s most innovative cyber companies,” according to its website. By spring 2019 Freedman was still losing $3 to $5 million a month on Hahnemann. He had burned through four CEOs in fifteen months. In June, hospital administrators announced that the facility was shutting down.

A facility that saw 53,000 emergency room visits per year disappeared from Philadelphia this summer with the prolonged and still-unfinished closure of Hahnemann University Hospital. The 496-bed hospital employed 2,700 people and saw 17,000 admissions in 2017, its last year under the management of the Tenet Healthcare Corporation. Tenet, one of the nation’s largest for-profit hospital conglomerates, owned ninety-six hospitals and nearly 500 outpatient centers in the United States that year. Not all of them turned a profit. Hahnemann, for example, booked $790 million in revenue in 2017, $115 million short of breaking even. So Tenet embarked on an international restructuring program, liquidating seventeen low-margin hospitals in the United States and the United Kingdom. In Philadelphia, Tenet sold Hahnemann to Joel Freedman, a man from Los Angeles who sat on the advisory board of the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics (his name has since been removed from the center’s website) and managed an investment fund, Paladin Capital, with interests in “the world’s most innovative cyber companies,” according to its website. By spring 2019 Freedman was still losing $3 to $5 million a month on Hahnemann. He had burned through four CEOs in fifteen months. In June, hospital administrators announced that the facility was shutting down. There is no escape from this dilemma – either all matter is conscious, or consciousness is something distinct from matter”: Alfred Russel Wallace put the point succinctly in 1870, and it is hard to see how his colleague

There is no escape from this dilemma – either all matter is conscious, or consciousness is something distinct from matter”: Alfred Russel Wallace put the point succinctly in 1870, and it is hard to see how his colleague  During the past eight years, many astute people, inside and outside the scientific community, have worried about the quality of scientific research. They warn of a “replication crisis.” In biomedicine and psychology in particular, it seems that a high proportion of published results cannot be reproduced. The absolute number of retractions for articles in these fields are rising. Whether or not it is right to talk of crisis, it is certainly reasonable to be concerned. What is going on?

During the past eight years, many astute people, inside and outside the scientific community, have worried about the quality of scientific research. They warn of a “replication crisis.” In biomedicine and psychology in particular, it seems that a high proportion of published results cannot be reproduced. The absolute number of retractions for articles in these fields are rising. Whether or not it is right to talk of crisis, it is certainly reasonable to be concerned. What is going on?

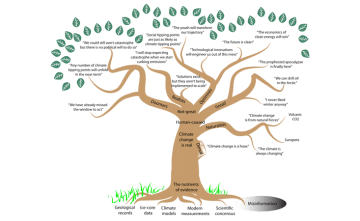

As a paleoclimatologist, I often find myself wondering why more people aren’t listening to the warnings, the data, the messages of climate woes—it’s not just a storm on the horizon, it’s here, knocking on the front door. In fact, it’s not even the front door anymore. You are on the roof, waiting for a helicopter to rescue you from your submerged house. The data is clear: The rates of current carbon dioxide release are 10 times greater than even the most rapid natural carbon catastrophe1 in the geological records, which brought about a miserable hothouse world of acidic oceans lacking oxygen, triggering a pulse of extinctions.2 Despite the evidence for anthropogenic climate change, views about the severity and impact of global warming diverge like branch points on a gnarly old oak tree (below).

As a paleoclimatologist, I often find myself wondering why more people aren’t listening to the warnings, the data, the messages of climate woes—it’s not just a storm on the horizon, it’s here, knocking on the front door. In fact, it’s not even the front door anymore. You are on the roof, waiting for a helicopter to rescue you from your submerged house. The data is clear: The rates of current carbon dioxide release are 10 times greater than even the most rapid natural carbon catastrophe1 in the geological records, which brought about a miserable hothouse world of acidic oceans lacking oxygen, triggering a pulse of extinctions.2 Despite the evidence for anthropogenic climate change, views about the severity and impact of global warming diverge like branch points on a gnarly old oak tree (below). Madison was never expected to live this long. The doctors had told her parents she would probably die at birth. Surprising everyone but her mother, she seized and trembled, and refused to suckle—but she didn’t die. Madison never learned to walk. Her four limbs were spastic. She remained small for her age, and she never learned to speak, not even to say Mama or milk, or no. But she saw and experienced many things beyond seizures, infections, breathing and feeding tubes; beyond Christmases and Easters and birthdays, and the everyday intimacies of childhood. She was her mother’s joy, and knew a fierce and indelible love, breathed over her in a nightly vigil. It imbued Madison with the quiet beauty of a survivor. Whatever trials she endured, there was a sense that she was lit from inside by something sacred.

Madison was never expected to live this long. The doctors had told her parents she would probably die at birth. Surprising everyone but her mother, she seized and trembled, and refused to suckle—but she didn’t die. Madison never learned to walk. Her four limbs were spastic. She remained small for her age, and she never learned to speak, not even to say Mama or milk, or no. But she saw and experienced many things beyond seizures, infections, breathing and feeding tubes; beyond Christmases and Easters and birthdays, and the everyday intimacies of childhood. She was her mother’s joy, and knew a fierce and indelible love, breathed over her in a nightly vigil. It imbued Madison with the quiet beauty of a survivor. Whatever trials she endured, there was a sense that she was lit from inside by something sacred. These days it is highly fashionable to label consciousness an ‘illusion’. This in turn fosters the impression, especially among the general public, that the way we normally think of our mental life has been shown by science to be drastically mistaken. While this is true in a very specific and technical sense, consciousness remains arguably the most distinctive evolved feature of humanity, enabling us not only to experience the world, like other animal species do, but to deliberately reflect on our experiences and to change the course of our lives accordingly.

These days it is highly fashionable to label consciousness an ‘illusion’. This in turn fosters the impression, especially among the general public, that the way we normally think of our mental life has been shown by science to be drastically mistaken. While this is true in a very specific and technical sense, consciousness remains arguably the most distinctive evolved feature of humanity, enabling us not only to experience the world, like other animal species do, but to deliberately reflect on our experiences and to change the course of our lives accordingly. Dennis, let’s start out by asking about the

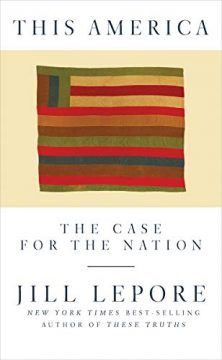

Dennis, let’s start out by asking about the  In her latest book, Jill Lepore, a brilliant story teller, offers us the biggest story of all: who we are and how we came to be. She did that superbly in her one-volume history of the nation, These Truths (2018). But here the effort is more pointed; here, Lepore is telling the story of the past in order to fight the battles of today, and she is urging her fellow historians to join her in the campaign. By mapping out the past as a competition between liberal and illiberal nationalisms, the latter most recently reincarnated and promoted by the President of the United States, Lepore is directly entering into the political fray. Unless liberals embrace and reclaim the idea of American nationalism, they will surrender its meaning to Trump and his supporters. What’s needed, and what her history shows is possible, is a full throated defense of civic patriotism, celebrating a “dedication to equality, citizenship, and equal rights, as guaranteed by a nation of laws.” “A new Americanism,” she writes on her final pages, “would mean a devotion to equality and liberty, tolerance and inquiry.”

In her latest book, Jill Lepore, a brilliant story teller, offers us the biggest story of all: who we are and how we came to be. She did that superbly in her one-volume history of the nation, These Truths (2018). But here the effort is more pointed; here, Lepore is telling the story of the past in order to fight the battles of today, and she is urging her fellow historians to join her in the campaign. By mapping out the past as a competition between liberal and illiberal nationalisms, the latter most recently reincarnated and promoted by the President of the United States, Lepore is directly entering into the political fray. Unless liberals embrace and reclaim the idea of American nationalism, they will surrender its meaning to Trump and his supporters. What’s needed, and what her history shows is possible, is a full throated defense of civic patriotism, celebrating a “dedication to equality, citizenship, and equal rights, as guaranteed by a nation of laws.” “A new Americanism,” she writes on her final pages, “would mean a devotion to equality and liberty, tolerance and inquiry.” Books, books, books. They will increase your lifespan, lower your stress and boost your intelligence. They will give you fuller, thicker hair.

Books, books, books. They will increase your lifespan, lower your stress and boost your intelligence. They will give you fuller, thicker hair. Luke Miller, a cognitive neuroscientist, was toying with a curtain rod in his apartment when he was struck by a strange realization. When he hit an object with the rod, even without looking, he could tell where it was making contact like it was a sensory extension of his body. “That’s kind of weird,” Miller recalls thinking to himself. “So I went [to the lab], and we played around with it in the lab.”

Luke Miller, a cognitive neuroscientist, was toying with a curtain rod in his apartment when he was struck by a strange realization. When he hit an object with the rod, even without looking, he could tell where it was making contact like it was a sensory extension of his body. “That’s kind of weird,” Miller recalls thinking to himself. “So I went [to the lab], and we played around with it in the lab.” The most glorious journey can begin with a mistake.” This is the observation made by Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio in the opening scene of Fernando Meirelles’s

The most glorious journey can begin with a mistake.” This is the observation made by Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio in the opening scene of Fernando Meirelles’s  Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s Aramco IPO last month was the biggest in world history.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s Aramco IPO last month was the biggest in world history.