Greta Lafleur in Public Books:

Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl tells a series of stories that we already know, but it achieves its familiar ends through decidedly unfamiliar means. Andrea Lawlor’s first novel presents us with the queer young adulthood of Paul, who possesses a seemingly magical skill: the ability to change form, to will his body into whatever shape he would like it to take.

Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl tells a series of stories that we already know, but it achieves its familiar ends through decidedly unfamiliar means. Andrea Lawlor’s first novel presents us with the queer young adulthood of Paul, who possesses a seemingly magical skill: the ability to change form, to will his body into whatever shape he would like it to take.

Beginning in Iowa City—where Paul and his best friend, Jane, share beer, coffee, and clothes as they commiserate about the challenges of being sexually ambitious young queer people in a small, Midwestern college town—Lawlor’s novel quickly removes to Michigan, to New York, to Provincetown, and to San Francisco, following Paul in his search for fun and experience throughout a geography familiar to many who were queer in the 1990s. And with every new setting, a new body: Paul proves a most effective sexual chameleon—jokingly referring to himself as a “replicant” and a “T-1000” (in the cultural idiom of the decade)—by changing form from leatherman to twink, femme dyke to punk faggot, depending on the social milieu and what seems most likely to get him laid.

Because of its locations, its desires, and its literary influences, this is a novel that creaks with the weight of familiarity; this is not a fault.

More here.

The answer is that the last century of science has partially recapitulated Aristotle’s teachings on nature, for the most part unwittingly. Since roughly the turn of the twentieth century, the scientific enterprise has focused not only on the elemental, but increasingly also on large-scale phenomena: solids, fluids, organisms, ecosystems, human behavior, and computing machines. Scientists have often maintained that these systems cannot be understood solely in terms of action at the lowest levels of organization. Thus one hears of “systems theory” or “the theory of complex systems,” of “holism,” “irreducibility,” “downward causation,” “information theory,” and other musings from scientists that assert, to quote the physicist Philip Anderson, that “

The answer is that the last century of science has partially recapitulated Aristotle’s teachings on nature, for the most part unwittingly. Since roughly the turn of the twentieth century, the scientific enterprise has focused not only on the elemental, but increasingly also on large-scale phenomena: solids, fluids, organisms, ecosystems, human behavior, and computing machines. Scientists have often maintained that these systems cannot be understood solely in terms of action at the lowest levels of organization. Thus one hears of “systems theory” or “the theory of complex systems,” of “holism,” “irreducibility,” “downward causation,” “information theory,” and other musings from scientists that assert, to quote the physicist Philip Anderson, that “ The art of Bill Traylor comes to us with the ghosts of slave ships, lynchings, chain gangs, Jim Crow, justice denied — an American night-story without end. Born in Alabama in 1853, Traylor was 9 years old when Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and 12 when slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment. He bore his owner’s name for life and resided for 55 years near the plantation where he was born; then he moved to nearby Montgomery County, where he remained until his death in 1949. In 1927 or 1928, he moved alone to the city of Montgomery, and in 1929, his son was killed by police. Ten years later, when Traylor was 85 and essentially homeless, he began to draw and paint on the streets of Montgomery, and a massive arc of art as powerful and profound as any in the 20th century shot out of him. His drawings and paintings in ink, pencil, and gouache were made on found cardboard, candy-box tops, and other odds and ends. Today, only four years of his output remain, yet we have about 1,200 works.

The art of Bill Traylor comes to us with the ghosts of slave ships, lynchings, chain gangs, Jim Crow, justice denied — an American night-story without end. Born in Alabama in 1853, Traylor was 9 years old when Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and 12 when slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment. He bore his owner’s name for life and resided for 55 years near the plantation where he was born; then he moved to nearby Montgomery County, where he remained until his death in 1949. In 1927 or 1928, he moved alone to the city of Montgomery, and in 1929, his son was killed by police. Ten years later, when Traylor was 85 and essentially homeless, he began to draw and paint on the streets of Montgomery, and a massive arc of art as powerful and profound as any in the 20th century shot out of him. His drawings and paintings in ink, pencil, and gouache were made on found cardboard, candy-box tops, and other odds and ends. Today, only four years of his output remain, yet we have about 1,200 works. In the early 20

In the early 20 Emily Dickinson’s poems are obsessed with youthful themes: fame, popularity, intense bouts of emotion and, of course, a fetishization of death. Her work isn’t changed in Dickinson. The stanzas are true to the source material. Modernizing the way characters speak to each other, but keeping the poems consistent, allows Dickinson’s words to feel more approachable for an audience that came into their own by way of Lil Peep Instagram live-streams and SoundCloud emo rap. Most brilliantly, Dickinson isn’t trying to be a teen show. That’s precisely why it works as one. It kind of stumbles into itself, finding its footing along the way. There isn’t any clear direction or structure to help it stay on the same path. Dickinson doesn’t shy away from ludicrousness, but leans into it unabashedly. It’s an “unapologetic, crying on the floor at two in the morning, flirting with the fetishization of death even when floating on the undeniable highness of life” type of disaster.

Emily Dickinson’s poems are obsessed with youthful themes: fame, popularity, intense bouts of emotion and, of course, a fetishization of death. Her work isn’t changed in Dickinson. The stanzas are true to the source material. Modernizing the way characters speak to each other, but keeping the poems consistent, allows Dickinson’s words to feel more approachable for an audience that came into their own by way of Lil Peep Instagram live-streams and SoundCloud emo rap. Most brilliantly, Dickinson isn’t trying to be a teen show. That’s precisely why it works as one. It kind of stumbles into itself, finding its footing along the way. There isn’t any clear direction or structure to help it stay on the same path. Dickinson doesn’t shy away from ludicrousness, but leans into it unabashedly. It’s an “unapologetic, crying on the floor at two in the morning, flirting with the fetishization of death even when floating on the undeniable highness of life” type of disaster.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

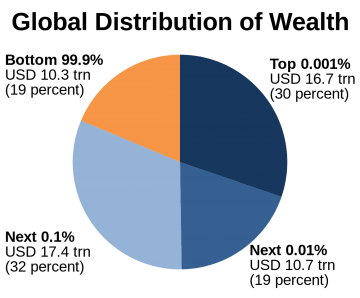

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.”

A 2011 survey by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely, of Harvard’s Business School, found that the average American thinks the richest 25% of Americans own 59% of the wealth, while the bottom fifth owns 9%. In fact, the richest 20% own 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% controls only 0.3%. An avalanche of studies has since confirmed these basic facts: Americans radically underestimate the amount of wealth inequality that exists – and the level of inequality they think is fair is lower than actual inequality in America probably has ever been. As journalist Chrystia Freeland put it, “Americans actually live in Russia, although they think they live in Sweden. And they would like to live on a kibbutz.” We are all aware that from amongst the vast diversity of life forms that inhabit the earth, human beings are exceptional. But while human beings are capable of inexhaustible creativity and goodness, they also have the potential to commit the most heinous acts and demeaning of fellow human beings. Accounting for such a phenomenon in the human condition and the committing of abominable acts towards their own species, is an issue that perplexes many. Perhaps the answer to such a question can be found by studying the genes or analysing the brain functioning of the perpetrators, but that could involve investigating entire populations who knowingly condone or participate in such acts. A simpler answer could be that human beings have yet to evolve into a species that is incapable of acts of inhumanity. David Livingstone Smith’s book Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others offers us insight into the processes that lead to the designating of fellow human beings as ‘subhuman’ and makes possible the potential for human beings to perpetrate acts that can only be considered as evil.

We are all aware that from amongst the vast diversity of life forms that inhabit the earth, human beings are exceptional. But while human beings are capable of inexhaustible creativity and goodness, they also have the potential to commit the most heinous acts and demeaning of fellow human beings. Accounting for such a phenomenon in the human condition and the committing of abominable acts towards their own species, is an issue that perplexes many. Perhaps the answer to such a question can be found by studying the genes or analysing the brain functioning of the perpetrators, but that could involve investigating entire populations who knowingly condone or participate in such acts. A simpler answer could be that human beings have yet to evolve into a species that is incapable of acts of inhumanity. David Livingstone Smith’s book Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others offers us insight into the processes that lead to the designating of fellow human beings as ‘subhuman’ and makes possible the potential for human beings to perpetrate acts that can only be considered as evil.