by Akim Reinhardt

Stuck is a new weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. A Prologue can be found here. A table of contents with links to previous chapters can be found here.

I never met Jeremy Spencer, so I can only guess. I suspect he was searching for something. Only 23 years old, perhaps he was unhappy with himself, or the world around him. Perhaps he was scared and craving shelter from the storm. Perhaps he dreamed of what could be, or pined for a grand voyage. Maybe he just got lost.

I never met Jeremy Spencer, so I can only guess. I suspect he was searching for something. Only 23 years old, perhaps he was unhappy with himself, or the world around him. Perhaps he was scared and craving shelter from the storm. Perhaps he dreamed of what could be, or pined for a grand voyage. Maybe he just got lost.

Either way, in 1971 Spencer went out for a magazine and never came back. When friends tracked him down several days later, they found he’d joined a small, new, secretive religious group called Children of God. Today it’s known as The Family International, and infamous for being the cult that the Phoenix children (including River and Joaquin) grew up in. According to Wikipedia, anyway, Spencer is still a member.

Prior to joining Children of God, Spencer had been a member of something else: Fleetwood Mac. And his departure from the band marked the second time in less than a year that one of their original guitarists had left to find God.

In 1970, founder Peter Green accepted an invitation to a German commune, where he made what he later described as “the most spiritual music” of his life. Suffering from schizophrenia and indulging in hallucinogenic drugs, Green told the band’s roadie that he didn’t want to return. The roadie fetched drummer Mick Fleetwood, and the two of them managed to convince Green to leave the commune. But soon after, Green insisted the band should donate all of its income to charities. The other members demurred. Green played his last show with them in May, and was gone.

Green had gotten his start by replacing Eric Clapton as the guitarist in John Mayall’s Blues Breakers after Clapton and bassist Jack Bruce left to form Cream. After a year with Mayall, Green also left to start his own band, inducing Bluesbreakers drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie to do join him. He even named the new band after them (“Mac” was McVie’s nickname). Under Green’s guidance, Fleetwood Mac developed a hard, electric blues sound modeled after American musicians like slide guitarist Elmore James. Their most notable song from these early days is Green’s “Black Magic Woman,” later made famous by Santana.

However, with Green and Spencer now each off on their own spiritual journeys, by 1971 the band was left adrift in Los Angeles during a U.S. tour. To survive, it would have to radically remake itself. McVie’s wife Christine (née Perfect, and formerly of the band Chicken Shack) had already been jamming with the group. She officially joined and began making substantive contributions as a keyboardist, singer, and songwriter. They also needed a new guitarist. On the recommendation of a friend, they recruited American Bob Welch without auditioning him in person or even listening to his demo tapes. Welch and Christine McVie now wrote much of the music, and reshaped Fleetwood Mac with more radio-friendly song craft. The smoother sound led to some commercial success, but the band’s tumult continued.

More musicians were hired and fired. Guitarist Danny Kirwin was let go after drunkenly smashing his guitar backstage and refusing to play a concert. Guitarist Bob Weston was canned after fucking Fleetwood’s wife, who also happened to be George Harrison’s sister-in-law. Meanwhile, the McVies’ marriage was crumbling as John’s drinking grew worse. Christine soon left John, and apparently her song “You Make Loving Fun” is about the lighting director on one of their tours, with whom she had an affair.

In 1974, amid the swirling chaos, the group’s own manager tried to pilfer the name “Fleetwood Mac” by spawning a counterfeit version of the band and putting it on the road. The real Fleetwood Mac’s road manager found out and hid the touring equipment. During the ensuing legal dispute, Welch convinced his band mates to move to Los Angeles.

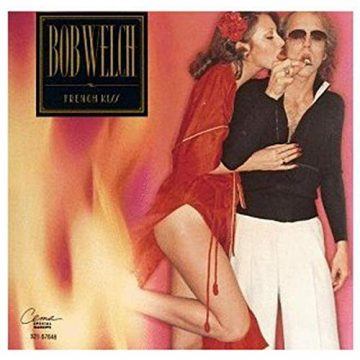

Soon after, Welch left to start a solo career. Three years later, he would score a massive hit by remaking a song he’d originally written and released with Fleetwood Mac. His new version of “Sentimental Lady” cracked the top 10 and, astonishingly, remained in the top 20 for nearly two years. On the album cover, a woman is tonguing Welch in the ear.

Meanwhile, Fleeetwood Mac was now down to just three core members and, once again, grasping for new musicians. In 1975 they brought in two little-known Americans: guitarist/singer/songwriter Lindsay Buckingham and singer/songwriter/proto-new age whirlwind Stevie Nicks. The band was reborn once more, featuring three different singer/songwriters and a longstanding, polished rhythm section. It was this version of Fleetwood Mac that took the musical world by storm.

The lineup’s first two albums were smash hits, and the second of those is among the most successful albums ever recorded. Rumors (1977) spawned four top 10 hits and was the #1 album on the Billboard U.S. chart for a stunning 31 weeks; to date, it has officially sold nearly 28,000,000 copies, with claimed sales of over 40,000,000. Both stats place it in the top ten selling albums of all time.

The lineup’s first two albums were smash hits, and the second of those is among the most successful albums ever recorded. Rumors (1977) spawned four top 10 hits and was the #1 album on the Billboard U.S. chart for a stunning 31 weeks; to date, it has officially sold nearly 28,000,000 copies, with claimed sales of over 40,000,000. Both stats place it in the top ten selling albums of all time.

I grew up with Rumors. My parents had a copy, and they played it with some frequency. I also had a very cool babysitter named Donna who was super stoked that my parents owned it. With Donna occasionally piloting a weekend afternoon for me and my three year old sister, we would listen to Rumors and dance around the apartment, stopping only to stare at the black and white photos on the record jacket and sleeve.

The five members of Fleetwood Mac seemed the quintessence of hip, or as best a 4th grader could understand the concept. Lindsay Buckingham’s ridiculously curly mop of hair and half-revealed chest; Christine McVie’s hoop earrings and head scarves; Mick Fleetwood’s gangly, wild-eyed clownishness; Stevie Nicks’ subtle, non-threatening, yet totally overpowering sexuality, so strong even a nine-year old boy could smell it emanating off the cardboard; and John McVie’s mild menace, replete with aviator sunglasses and hairy forearms. In the gatefold photo, McVie looks like he could either be cleaning his ear or pointing a mock gun to his head.

Though I can’t find it now, I distinctly remember staring at one band photo where McVie, or perhaps Buckingham, was simultaneously smoking a cigarette and drinking a bottle of booze. My parents smoked and drank, so that was nothing new, but I never knew you could do both at the same time. It was a minor revelation. When I eagerly showed it to her later, my mother was less impressed.

If you had to pick a ubiquitous album to spend a lot of time with as a kid, Rumors is a pretty good choice. It’s a pop masterpiece. Every song on the album is at the very least quite good, and some of them are downright great. There are certainly worse albums to know inside and out.

However, after becoming so well versed in the album during childhood, I didn’t bother listening to it straight through probably after the age of 14, eventually handing it down to my sister. As Rumors faded into memory, I eventually came under the mistaken impression that it contained pretty much every 1970s Fleetwood Mac hit. This was because I knew nothing of the record that preceded it, 1975’s Fleetwood Mac, the band’s tenth album overall. I had no idea that it too was a multi-million selling chart topper, boasted a bevy hits that remain radio staples, and was actually the album that actually launched the band’s soaring fame spiral. In fact, I somehow didn’t find this out until a couple of weeks ago when I was driving around town with my friend Mike.

Mike’s a musical co-conspirator of sorts. Originally from California, he spent about fifteen years playing drums in L.A. and S.F punk bands. We jam once in a while and talk about music a fair bit. As we tootled around town in his wife’s car, the discussion turned to Fleetwood Mac, and we bickered over who was the best songwriter of the three. Mike was partial to Nicks and didn’t care for McVie, while I thought Nicks was great but perhaps overrated and McVie was underrated.

It turned out CDs of both Fleetwood Mac and Rumours were in the car. I popped in the former since it contained a Nicks song Mike wanted to use to make his case. But instead of fast forwarding to the track he wanted to hear, I allowed the album to start naturally. And that’s when I got confused.

The opener was instantly familiar, yet not fully ingrained in my mind like the songs from Rumors. It was “Monday Morning” by Lindsay Buckingham.

I felt slightly disoriented as I pulled the sleeve from the jewel case, trying make sense of everything. The song had that distinctive Buckingham sound. His folk/rock guitar playing, chord structures, and arrangements are all there. So too is his consistent lyrical theme: resentment and bitterness over his romantic breakup with Nicks.

Not long after, Nicks and Mick Fleetwood started having an affair. You need a goddamn flow chart to figure out who’s fucking whom.

But at that moment, I wasn’t concerned with the band’s romantic peccadilloes. I was busy trying to process “Monday Morning,” a fully formed Buckingham song that sounded like it easily could have, and in my mind should have, been on Rumors. Yet I barely knew it.

For the rest our time in the car, the conversation was shaped by my effort to get through the entire album before we got to my house, which I accomplished with a little skipping around. Listening to it was a revelation.

As the CD progressed, it quickly became apparent that Stevie Nicks and Christine McVie dominate the album. They wrote most of the songs and nearly all the hits. It turned out I already knew half the songs, some of them very well. The only tune that I assumed would be on the album (once I learned of its existence) was Nicks’ “Rhiannon.” Much of the rest was familiar but confusing. I grew up hearing McVie’s “Over My Head” on the radio, but if I’d had to guess who sang it, I might’ve said Crystal Gayle or Nicolette Larson. And when I heard McVie’s “Say You Love Me,” I was truly confounded; I already knew it was a Fleetwood Mac song, and I was so familiar with it that I would’ve sworn up and down on a stack of Family International bibles that it was on Rumors.

Having grown up with Rumors, listening to Fleetwood Mac for the first time in 2013 was like discovering the great, long lost Fleetwood Mac album. For a few moments, it seemed as if my childhood had been conjured from the mist, my sister and I jumping up and down on the green, velour living room couch as Donna spun vinyl.

Many of the album’s songs felt like family members whose relation you didn’t actually understand until you are an adult because it turns out you were born out of wedlock, and are just now finding out that these “aunts” and “uncles” are actually your older siblings, which helps explain why you love them so goddamn much. You’ve known them all your life, and now it felt like you were getting to meet them again for the first time.

Then Mike pulled up in front of my house. After making a final plea for Christine McVie’s talents as a songwriter, I got out of his car, went inside my house, walked upstairs to my office, sat down at the desk, and opened the top right drawer. I pulled out my messy pile of old family photos, began flipping through them, and tried to remember who we all might have been.

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com