by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

In 1973 Betty Friedan traveled to France to have a conversation about the state of feminism with Simone de Beauvoir, whom she regarded as a cultural hero. Friedan’s own opinions had evolved considerably in the decade since the publication of The Feminine Mystique. She would elaborate those changes sometime later in a new book, The Second Stage, in which she argued for women’s work in the home to be viewed as “real work” and included in the gross national product. Now, in her meeting with Beauvoir, Friedan asked her opinion on ways to recognize the value of that work, such as crediting it for social security purposes, or distributing vouchers which parents could either use to buy childcare or collect on themselves as full-time caregivers. Perhaps Friedan wondered if Beauvoir’s thinking too might have changed since she stated in The Second Sex that the work of a woman at home “is not directly useful to society, it does not open out on the future, it produces nothing.” If so, she got her answer: Beauvoir, holding out for a total remake of society, believed that even in the meantime “No woman should be authorized to stay at home to raise her children …. Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make that one.”

Rhetoric is one thing, and given the many ideological variations within the women’s movement, any attempt to attribute to it some particular position on women’s work in the home would almost certainly invite fierce disagreement. But it is much harder to dispute what has actually happened in the last half-century. In certain respects the women’s movement has had enormous success. Women’s levels of education, employment, and income have all surged. In that sense the situations of men and women are far more alike than they once were. Through their inroads into realms previously closed to them, women have obtained a share of the status which was once conferred far more heavily on men.

I would be hard-pressed to say, though, that there has been any improvement in the status of “women’s work.” (I mean by that the traditional work of women, whether performed by women or by men.) The essential functions without which no society can exist – the care of children, the preparation of food, the keeping of a house, the care of the elderly and infirm – continue to be devalued. Read more »

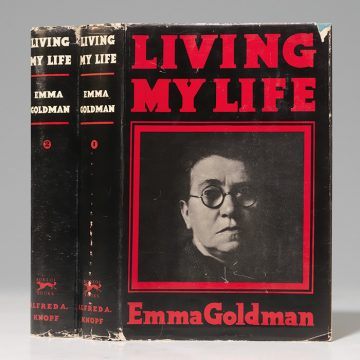

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life. On its glittering surface, America’s corporate economy appears to be in fantastic shape. The stock markets recently reached record highs, even if they dipped and bobbed after reaching those heights. Profits are soaring. Financing is cheap. The corporate tax rate has been cut. The unemployment rate is near a fifty-year low, with little inflation.

On its glittering surface, America’s corporate economy appears to be in fantastic shape. The stock markets recently reached record highs, even if they dipped and bobbed after reaching those heights. Profits are soaring. Financing is cheap. The corporate tax rate has been cut. The unemployment rate is near a fifty-year low, with little inflation. Bob Marra

Bob Marra

“I think I can safely say that nobody really understands quantum mechanics,” observed the physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman. That’s not surprising, as far as it goes. Science makes progress by confronting our lack of understanding, and quantum mechanics has a reputation for being especially mysterious.

“I think I can safely say that nobody really understands quantum mechanics,” observed the physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman. That’s not surprising, as far as it goes. Science makes progress by confronting our lack of understanding, and quantum mechanics has a reputation for being especially mysterious. The sleek blue-glass building of the Infosys corporation sits like an intruding spaceship amid the unpaved side streets and half-completed residential structures that surround it. Its giant porthole windows offer a peek into a Jetsons-esque world of workers gliding between floors on elevated moving sidewalks. For now, 19-year-old Nishank Nachappaa toils in the shadows of Infosys and the other high-tech companies that, like him, call the Electronic City section of Bangalore home. The high school graduate helps out at two dormitories for tech workers – one for young men, the other for young women – that his parents manage. His father maintains the buildings and his mother prepares meals for the 120 male and 30 female residents. Walk a block or two from the dorms and other corporate structures loom with multinational names such as Emerson and Yokogawa, Altametrics and Hewlett Packard.

The sleek blue-glass building of the Infosys corporation sits like an intruding spaceship amid the unpaved side streets and half-completed residential structures that surround it. Its giant porthole windows offer a peek into a Jetsons-esque world of workers gliding between floors on elevated moving sidewalks. For now, 19-year-old Nishank Nachappaa toils in the shadows of Infosys and the other high-tech companies that, like him, call the Electronic City section of Bangalore home. The high school graduate helps out at two dormitories for tech workers – one for young men, the other for young women – that his parents manage. His father maintains the buildings and his mother prepares meals for the 120 male and 30 female residents. Walk a block or two from the dorms and other corporate structures loom with multinational names such as Emerson and Yokogawa, Altametrics and Hewlett Packard.

Like many other nations, Canada is blessed with enormous resource wealth. We are the 7th largest oil-producing nation in the world (Norway is the 15th), with vast forests, mineral deposits and prime farming land. The Canadian province of Alberta legally controls almost 80 percent of the country’s fossil fuel production, has a similar population to Norway yet somehow managed to end up with a

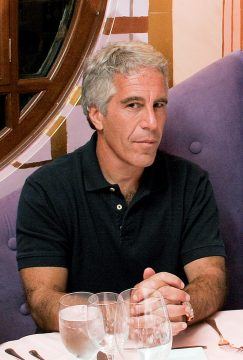

Like many other nations, Canada is blessed with enormous resource wealth. We are the 7th largest oil-producing nation in the world (Norway is the 15th), with vast forests, mineral deposits and prime farming land. The Canadian province of Alberta legally controls almost 80 percent of the country’s fossil fuel production, has a similar population to Norway yet somehow managed to end up with a  The M.I.T. Media Lab, which has been embroiled in a scandal over accepting donations from the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, had a deeper fund-raising relationship with Epstein than it has previously acknowledged, and it attempted to conceal the extent of its contacts with him. Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as “disqualified” in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university. Perhaps most notably, Epstein appeared to serve as an intermediary between the lab and other wealthy donors, soliciting millions of dollars in donations from individuals and organizations, including the technologist and philanthropist Bill Gates and the investor Leon Black. According to the records obtained by The New Yorker and accounts from current and former faculty and staff of the media lab, Epstein was credited with securing at least $7.5 million in donations for the lab, including two million dollars from Gates and $5.5 million from Black, gifts the e-mails describe as “directed” by Epstein or made at his behest. The effort to conceal the lab’s contact with Epstein was so widely known that some staff in the office of the lab’s director, Joi Ito, referred to Epstein as Voldemort or “he who must not be named.”

The M.I.T. Media Lab, which has been embroiled in a scandal over accepting donations from the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, had a deeper fund-raising relationship with Epstein than it has previously acknowledged, and it attempted to conceal the extent of its contacts with him. Dozens of pages of e-mails and other documents obtained by The New Yorker reveal that, although Epstein was listed as “disqualified” in M.I.T.’s official donor database, the Media Lab continued to accept gifts from him, consulted him about the use of the funds, and, by marking his contributions as anonymous, avoided disclosing their full extent, both publicly and within the university. Perhaps most notably, Epstein appeared to serve as an intermediary between the lab and other wealthy donors, soliciting millions of dollars in donations from individuals and organizations, including the technologist and philanthropist Bill Gates and the investor Leon Black. According to the records obtained by The New Yorker and accounts from current and former faculty and staff of the media lab, Epstein was credited with securing at least $7.5 million in donations for the lab, including two million dollars from Gates and $5.5 million from Black, gifts the e-mails describe as “directed” by Epstein or made at his behest. The effort to conceal the lab’s contact with Epstein was so widely known that some staff in the office of the lab’s director, Joi Ito, referred to Epstein as Voldemort or “he who must not be named.” AS A MEDICAL STUDENT

AS A MEDICAL STUDENT

Ted Mann in Tablet:

Ted Mann in Tablet: