Jenny Uglow in the New York Review of Books:

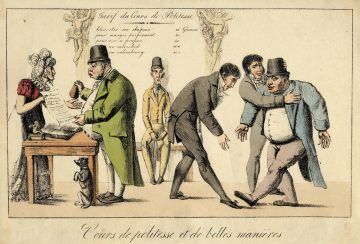

“Civility,” Keith Thomas notes in this absorbing book, “was (and is) a slippery and unstable word.” “Civil” and “civilian” evoke the social life of a people not under military rule, the world of the civitas—the organized community—the only place, according to Aristotle and Cicero, where the good life is possible. While “courtesy” relates to the values of the court, “civility,” Thomas writes, is “the virtue of citizens”: in his Dictionary (1755), Samuel Johnson defined it as both “politeness” and “the state of being civilized.” Thomas explores the understanding and use of the term in England from 1500 to 1800, when it referred both to manners in daily life and manners as mores: the customs and attitudes of the allegedly civilized nation as a whole.

In its wider sense, the ideal of civility was orderly government, with a populace accepting its laws and prescribed moral standards as well as adhering to the hierarchical structure of society and the strict but subtle dictates of class and decorum (the chief one being “know your place”). In Britain, “civil government” reflected the interests of the moneyed classes: the protection of private property and the value of trustworthiness, essential for a credit-based economy. In time, the idea of civility also came to embrace an interest in the arts and sciences, and—at least in theory—religious toleration, open debate, and the freedom to disagree.

More here.