Bennett McIntosh in Harvard Magazine:

AS A MEDICAL STUDENT in the 1980s, Isaac “Zak” Kohane heard stories—from patients, mentors, and colleagues—of nearly miraculous recoveries from cancer. A patient given weeks to live instead survives for years. An experimental drug works exceptionally well—in only one patient. Or, most controversially, a patient rejects chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, and somehow lives. As a trainee, Kohane found many such stories quite literally unbelievable. “Frankly,” he says, “I assumed that they didn’t really have a cancer.” Now Nelson professor of biomedical informatics at Harvard Medical School (see “Toward Precision Medicine,” May-June 2015, page 17), Kohane not only believes these stories, he’s seeking them out. A year ago, he began a project to find “exceptional responders” to cancer treatment—those who have beaten the cancer odds many times over—in order to figure out what makes them special.

AS A MEDICAL STUDENT in the 1980s, Isaac “Zak” Kohane heard stories—from patients, mentors, and colleagues—of nearly miraculous recoveries from cancer. A patient given weeks to live instead survives for years. An experimental drug works exceptionally well—in only one patient. Or, most controversially, a patient rejects chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, and somehow lives. As a trainee, Kohane found many such stories quite literally unbelievable. “Frankly,” he says, “I assumed that they didn’t really have a cancer.” Now Nelson professor of biomedical informatics at Harvard Medical School (see “Toward Precision Medicine,” May-June 2015, page 17), Kohane not only believes these stories, he’s seeking them out. A year ago, he began a project to find “exceptional responders” to cancer treatment—those who have beaten the cancer odds many times over—in order to figure out what makes them special.

He was inspired initially by a very different group of patients. Since 2014, Kohane has coordinated a nationwide program to study and aid patients whose affliction with rare, undiagnosed diseases mark them as statistical outliers. “Outliers, by definition, are interesting,” he explains, because they are different from everybody else, “so there are things to be learned. By finding these outliers, we have been able to make breakthroughs both for the patient but also scientifically,” diagnosing more than 300 patients suffering from newly discovered genetic diseases in five years.

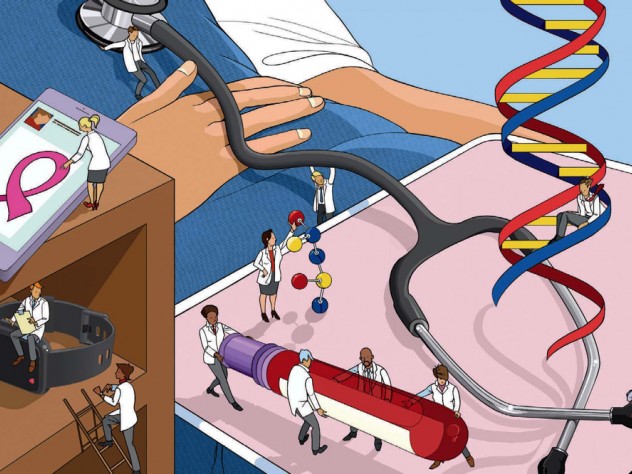

By investigating exceptional responders, Kohane now hopes to find new paths to cancer treatment, rather than new diseases. The study has thus far recruited more than 75 participants from around the United States, representing 24 different types of cancer. Many of the subjects responded exceptionally well to a conventional combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy; others took part in clinical trials of new therapies, and were profoundly successful. At least one survived with no conventional therapy at all. By collecting as much data as possible from these patients—sequencing their DNA, inventorying their gut microbes, and even asking them for access to data from their social- media pages and FitBit fitness trackers—Kohane hopes to draw connections between their successes and the underlying causes that may have saved them.

More here.