I was about to board this Frecciargento fast train from Bozen to Verona last week when I noticed how nicely the shape of the train matched the shape of the mountain in the background.

Month: August 2019

A Homecoming

by Tamuira Reid

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

The apartment in West Harlem, five buildings down on the left. The apartment just past the pawn shop, across from the Rite-Aid, parallel to the barber’s where all the pretty boys hangout waiting to get a Friday night shave. The apartment past the deli were you get cheese and pickle sandwiches and the all-night liquor store and the ATM machine no one is dumb enough to use.

The apartment at the top of the stairs with the impossibly high ceilings and the blue bathroom door, the door you labor behind for twelve hours before going to the hospital, your body threatening to push another body out. The apartment where you bring him home, his pink baby body covered in muslin and sweat. The apartment with the wide cracked stoop where you rest with his father just long enough to catch your breath, to say holy shit, he’s beautiful.

The apartment you now stand in front of, seven years later, holding onto a box of birthday-wrapped legos and your son’s hand. The apartment at Broadway and 138th. The apartment on the way to the party. The apartment half-way down a steep hill, the hill you lug your grocery bags down, and the hill you climb with your luggage. The apartment with a broken oven but perfect sunlight and enough closets to hide things in. The apartment in an old brownstone next to other old brownstones, framed by planter boxes filled with tulips and beer cans and night club fliers. The apartment owned by an angry old man and his needy young wife, a man who is stretched so thin he could give two fucks when you tell him the heat is out. The apartment where you sleep in a pile for warmth, arms and legs wrapped around one another, the baby squished between across the two of you. Read more »

Holy Ghost Story

by Shawn Crawford

Preachers at our Baptist church had to ask for an Amen. We weren’t just going to spontaneously let one loose. God can’t drive a parked car, my youth minister would say. Meaning you had to exert your own will as well in the pursuit of a righteous life. When it came to the Holy Spirit, we rarely even tried the ignition.

After the death of Christ, the apostles found themselves a pretty sorry lot. Scared and convinced they were the next candidates for execution, most went into hiding. What transformed them was not merely the appearance of the resurrected Jesus, but the gift of the Holy Spirit, and this gift came to them through the sound of a rushing wind and tongues of fire that descended from heaven and “came to rest on each of them” (Acts 2.3). The depiction of this event generally involves little candle flames hovering over the Apostles. As if that wasn’t cool enough, the first thing that happened for the Apostles was the ability to speak in languages they had never known. Which came in handy, because it just so happened Jews all over the world had gathered in Jerusalem for Pentecost, a derivation of a Greek word that means “fifty” and denoted the fiftieth day after Passover and the beginning of the next Jewish holiday Shavuot. Peter gave the first sermon on the need for repentance and baptism, the Christian church began, and the word Pentecost became associated with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues, which would eventually spawn a focus on such practices in Pentecostal churches. Read more »

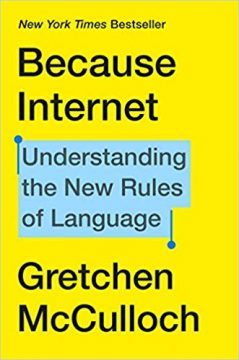

Book review: Because Internet, by Gretchen McCulloch

Stan Carey in Sentence First:

Language is always changing, and on a macro level some of the most radical changes have resulted from technology. Writing is the prime example. Millennia after its development, telephony reshaped our communication; mere decades later, computers arrived, became networked, and here I am, typing something for you to read on your PC or phone, however many miles away.

Language is always changing, and on a macro level some of the most radical changes have resulted from technology. Writing is the prime example. Millennia after its development, telephony reshaped our communication; mere decades later, computers arrived, became networked, and here I am, typing something for you to read on your PC or phone, however many miles away.

The internet’s effects on our use of language are still being unpacked. We are in the midst of a dizzying surge in interconnectivity, and it can be hard to step back and understand just what is happening to language in the early 21st century. Why are full stops often omitted now? What exactly are emoji doing? Why do people lol if they’re not laughing? With memes, can you even?

Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language is a new book by linguist Gretchen McCulloch that sets out to demystify some of the strange shifts going on in language right now. It provides a friendly yet substantial snapshot of linguistic trends and phenomena online, and it explains with clarity and ebullience what underpins them – socially, psychologically, technologically, linguistically.

More here.

Universal emotions are the deep engine of human consciousness and the basis of our profound affinity with other animals

Stephen T Asma in Aeon:

Charles Darwin closed his On the Origin of Species (1870) with a provocative promise that ‘light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history’. In his later books The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin shed some of that promised light, especially on the evolved emotional and cognitive capacities that humans shared with other mammals. In one scandalous passage, he demonstrated that four ‘defining’ characteristics of Homo sapiens – tool use, language, aesthetic sensitivity and religion – are all present, if rudimentary, in nonhuman animals. Even morality, he argued, arose through natural selection. Altruistic self-sacrifice might not give the individual a survival advantage, but, he wrote:

Charles Darwin closed his On the Origin of Species (1870) with a provocative promise that ‘light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history’. In his later books The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), Darwin shed some of that promised light, especially on the evolved emotional and cognitive capacities that humans shared with other mammals. In one scandalous passage, he demonstrated that four ‘defining’ characteristics of Homo sapiens – tool use, language, aesthetic sensitivity and religion – are all present, if rudimentary, in nonhuman animals. Even morality, he argued, arose through natural selection. Altruistic self-sacrifice might not give the individual a survival advantage, but, he wrote:

There can be no doubt that a tribe including many members who, from possessing in a high degree the spirit of patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, and sympathy, were always ready to aid one another, and to sacrifice themselves for the common good, would be victorious over most other tribes; and this would be natural selection.

Yet Darwin’s revolutionary understanding of the evolved nature of human emotions has been neglected since. When scientists turned again to the mind a century later, the computer was the model that both sparked the cognitive sciences revolution and served as its exclusive investigative tool. The computational model of the mind has been very powerful, but it has no way (and no need) to capture the biological ingredient of motivational feeling-states, and has been unconcerned with the evolved substrate to such processes.

More here.

Terrorism and the Crisis of Deliberative Democracy

Scott Atran in Psychology Today:

The spread of substate and transnational forms of terrorism that target ordinary civilians for mass murder tears at the social and political consensus in our country and across the world. The aim is to create the void that will usher in a new world, with no room for innocents on the other side, or in the “Gray Zone” between that includes most of humanity.

The spread of substate and transnational forms of terrorism that target ordinary civilians for mass murder tears at the social and political consensus in our country and across the world. The aim is to create the void that will usher in a new world, with no room for innocents on the other side, or in the “Gray Zone” between that includes most of humanity.

For 21-year-old Patrick Crusius, who killed 22 people and wounded 24 in El Paso earlier this month, terminating the brown invasion of Hispanics that soils White America to the advantage of the Democratic Party requires mass civilian deaths to save civilization—a mission that ISIS shares, albeit with a different, if equally exclusive, end in mind.

The values of liberal and open democracy increasingly appear to be losing ground to those of narrow, xenophobic ethno-nationalisms and radical religious ideologies. These seemingly opposed movements, our research team at Artis International and the Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict at Oxford University has found, in fact tacitly collaborate to undermine free and open societies today, much like Fascists and Communists did back in the 1920s and 30s.

Reasons To Be Cheerful: A Talk by David Byrne

It was legal teams—not politicians—that ultimately held the tobacco industry to account. Their next target? Perpetrators of climate change

Mitch Anderson at Reasons to be Cheerful:

Lawyers are one of America’s most distrusted professions, bringing up the rear behind even bankers and local politicians. But what if lawyers end up saving the world?

Lawyers are one of America’s most distrusted professions, bringing up the rear behind even bankers and local politicians. But what if lawyers end up saving the world?

Scientists have been warning for years that mounting carbon emissions are dangerously destabilizing our climate. Efforts to tackle this urgent challenge through the political process have so far come up far short of the action needed to avoid some very bad outcomes.

Can litigation succeed where politics has so far failed?

We’ve actually been here before. Several decades ago it also seemed the tobacco industry was an invincible foe to public health. Over the course of decades, however, a series of long-shot lawsuits finally enfeebled this previously unassailable political lobby. Civil litigation against cigarette manufacturers began in the 1950s, but did not bear fruit until 40 years later in a series of court victories that culminated in the $206 billion Master Settlement Agreement with 46 U.S. states.

Terms of this judgment included halting advertising smoking to children, funding anti-smoking campaigns with industry money and dissolving three of the biggest tobacco industry organizations.

More here.

Nancy Reddin Kienholz (1943 – 2019)

The Loneliest of Species

Jay Griffiths in Lapham’s Quarterly:

The long-tailed macaques leap like embodied jokes, making the very trees laugh with their sense of swing. A baby monkey jumps from liana to liana, curls its fingers around a branch, and dives into a stream: aerial then aquatic acrobatics. A gecko runs up a buttress flank of mahogany and freezes, alert, silently glued to the trunk, its tiny tongue licking up termites. High in the trees, a Thomas’ leaf monkey, with its long white tail, whiskers, and mohawk, blinks and gazes, blinks and gazes. The Sumatran rain forest, filled with the jungle music of crickets and frogs, is home to all the creatures of The Jungle Book. I’d been invited to join an ecotourist trek to see orangutans, a critically endangered animal. The hope of seeing one was only a part of my delight: to put it simply, forests make me happy.

Academia demonstrates what the heart already knows: nature-connectedness is correlated with emotional and psychological well-being, from the Japanese shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) to the joy inherent in Norwegian friluftsliv (free-air life) or the rush of oxytocin in dog owners when gazing into their dogs’ eyes. It is easier, of course, to love one’s cat than to care about the chestnut clearwing moth or the rufous-fronted laughing thrush, but pets can be the ambassadors of the natural world, leading us by the paw into a world richer than we could ever know by ourselves.

When a wild landscape is lit with birds and ribboned with animal presence, it tells us that all manner of living things are well, and it draws us inextricably into a shared happiness, whether in a savanna or rain forest or the woodland humming with joy evoked by Tennyson’s lines of “doves in immemorial elms / And murmuring of innumerable bees.” Thus the giraffes who caress one another with low hums, a gentle evening song of the envoiced world. Thus puffins, clowns of the air, possibly the most visually cheering of all birds. Thus rats, who if tickled chirp like children laughing, while bonobos, if tickled, laugh until they fart. Laughter is a signal, a form of communication that tells others that the laugher is not only happy but wishes to spend more time with the laughee, welcoming the exchange as reciprocal. When we respect the fact that all species are necessary to the well-being of an ecosystem, this sense of shared happiness can potentially include everything, from baby elephants at play to the leeches that crawl up our legs as we walk through the forests of Sumatra.

More here.

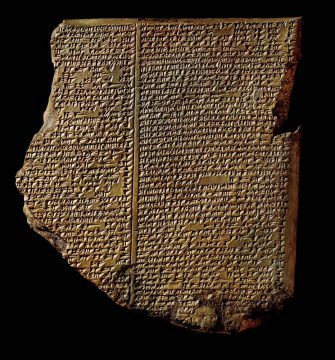

A World of Literature

Spence Lenfield in Harvard Magazine:

THE RÉSUMÉ of Harvard’s Bernbaum professor of comparative literature might create the impression that “comp lit” means “the study of any literature from anywhere, ever.” At various points in his career, David Damrosch has written about the epic of Gilgamesh, the Hebrew Bible, the Sanskrit verse dramatist Ka-lida-sa, visions of medieval Belgian nuns, Aztec poetry, Kafka, the Chinese intellectual Hu Shih, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, and the oral autobiography of K’iche’ Guatemalan Nobel laureate and activist Rigoberta Menchú. Most scholars define themselves as specialists in one or two centuries of one or two regions; Damrosch’s work across time and space makes him an outlier. He says he tells people, “I work mostly on literature between roughly 2000 and 2015. But ‘2000’ means 2000 B.C.E.”

THE RÉSUMÉ of Harvard’s Bernbaum professor of comparative literature might create the impression that “comp lit” means “the study of any literature from anywhere, ever.” At various points in his career, David Damrosch has written about the epic of Gilgamesh, the Hebrew Bible, the Sanskrit verse dramatist Ka-lida-sa, visions of medieval Belgian nuns, Aztec poetry, Kafka, the Chinese intellectual Hu Shih, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, and the oral autobiography of K’iche’ Guatemalan Nobel laureate and activist Rigoberta Menchú. Most scholars define themselves as specialists in one or two centuries of one or two regions; Damrosch’s work across time and space makes him an outlier. He says he tells people, “I work mostly on literature between roughly 2000 and 2015. But ‘2000’ means 2000 B.C.E.”

He is best known for his advocacy of “world literature,” which he defines in his (sensibly titled) 2003 book What Is World Literature? as “all literary works that circulate beyond their culture of origin, either in translation or in their original language.” This does notmean all literature ever created: some stays within the culture and language that produced it, and never leaves. World literature happens when Russian novels remake English literature; when a Turkish writer takes inspiration from a Colombian writer; when Japanese critics review translations of Lebanese poetry. It almost always involves re-interpretation and misunderstanding: a Spanish monk sent to suppress Aztec literature ended up disseminating it instead; subsequently, Aztec hymns envision a Christian God urging revolt against the Spaniards. World literature is also nothing new under the sun: Damrosch’s first book, Narrative Covenant, is about the influence of a range of Mesopotamian literatures from the first millennium B.C.E. on the composition of much of the Bible.

More here.

How Life Became an Endless, Terrible Competition

Daniel Markovits in The Atlantic:

Two decades ago, when I started writing about economic inequality, meritocracy seemed more likely a cure than a cause. Meritocracy’s early advocates championed social mobility. In the 1960s, for instance, Yale President Kingman Brewster brought meritocratic admissions to the universitywith the express aim of breaking a hereditary elite. Alumni had long believed that their sons had a birthright to follow them to Yale; now prospective students would gain admission based on achievement rather than breeding. Meritocracy—for a time—replaced complacent insiders with talented and hardworking outsiders.Today’s meritocrats still claim to get ahead through talent and effort, using means open to anyone. In practice, however, meritocracy now excludes everyone outside of a narrow elite. Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale collectively enroll more students from households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from households in the bottom 60 percent. Legacy preferences, nepotism, and outright fraud continue to give rich applicants corrupt advantages. But the dominant causes of this skew toward wealth can be traced to meritocracy. On average, children whose parents make more than $200,000 a year score about 250 points higher on the SAT than children whose parents make $40,000 to $60,000. Only about one in 200 children from the poorest third of households achieves SAT scores at Yale’s median. Meanwhile, the top banks and law firms, along with other high-paying employers, recruit almost exclusively from a few elite colleges.

Two decades ago, when I started writing about economic inequality, meritocracy seemed more likely a cure than a cause. Meritocracy’s early advocates championed social mobility. In the 1960s, for instance, Yale President Kingman Brewster brought meritocratic admissions to the universitywith the express aim of breaking a hereditary elite. Alumni had long believed that their sons had a birthright to follow them to Yale; now prospective students would gain admission based on achievement rather than breeding. Meritocracy—for a time—replaced complacent insiders with talented and hardworking outsiders.Today’s meritocrats still claim to get ahead through talent and effort, using means open to anyone. In practice, however, meritocracy now excludes everyone outside of a narrow elite. Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and Yale collectively enroll more students from households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution than from households in the bottom 60 percent. Legacy preferences, nepotism, and outright fraud continue to give rich applicants corrupt advantages. But the dominant causes of this skew toward wealth can be traced to meritocracy. On average, children whose parents make more than $200,000 a year score about 250 points higher on the SAT than children whose parents make $40,000 to $60,000. Only about one in 200 children from the poorest third of households achieves SAT scores at Yale’s median. Meanwhile, the top banks and law firms, along with other high-paying employers, recruit almost exclusively from a few elite colleges.

Hardworking outsiders no longer enjoy genuine opportunity. According to one study, only one out of every 100 children born into the poorest fifth of households, and fewer than one out of every 50 children born into the middle fifth, will join the top 5 percent. Absolute economic mobility is also declining—the odds that a middle-class child will outearn his parents have fallen by more than half since mid-century—and the drop is greater among the middle class than among the poor. Meritocracy frames this exclusion as a failure to measure up, adding a moral insult to economic injury.

More here.

Sunday Poem

One of the Citizens

What we have here is a mechanic who reads Nietzsche,

who talks of the English and French Romantics

as he grinds the pistons; who takes apart the Christians

as he plunges the tarred sprockets and gummy bolts

into the mineral spirits that have numbed his fingers;

an existentialist who dropped out of school to enlist,

who lied and said he was eighteen, who gorged himself

all afternoon with cheese and bologna to make the weight

and guarded a Korean hill before he roofed houses,

first in East Texas, the here in North Alabama. Now

his work is logic and the sure memory of disassembly.

As he dismantles the engine, he will point out damage

and use, the bent nuts, the worn shims of uneasy agreement.

He will show you the scar behind each ear where they

put in the plates. He will tap his head like a kettle

where the shrapnel hit, and now history leaks from him,

the slow guile of diplomacy and the gold war makes,

betrayal at Yalta and the barbed wall circling Berlin.

As he sharpens the blades, he will whisper of Ruby and Ray.

As he adjusts the carburetors, he will tell you

of finer carburetors, invented in Omaha, killed by Detroit,

of deals that fall like dice in the world’s casinos,

and of the commission in New York that runs everything.

Despiser of miracles, of engineers, he is as drawn

by conspiracies as his wife by the gossip of princesses,

and he longs for the definitive payola of the ultimate fix.

Read more »

London’s Memorial Church Ruins

Altair Brandon-Salmon at Commonweal:

In the booklet’s foreword, the Very Reverend W. R. Matthews, then the Dean of St. Paul’s, claimed that “the devastation of war has given us an opportunity which will never come again.” This optimism echoed sentiments expressed during the war itself. The country would turn bombsites into social housing and hospitals, with a few churches left as memorials to the carnage of the home front. (As Brian Foss has pointed out, it wasn’t until September 1941 that frontline casualties outnumbered civilian deaths in Britain.) The short booklet is full of halftone illustrations, architectural plans, and garden plans, showing how to transform destroyed buildings into “ruins.” In one article, Hugh Casson argued that “every stone—whether fallen or in place—is a fragment of the past, part of the pattern of history.” Churches such as St. Dunstan and Christ Church, Newgate Street, scarred by the Great Fire of London and the Blitz, are now living monuments not just to the bombs and fires, but to London’s long history of transformation. Casson worried about a time when “all traces of war damage will have gone, and its strange beauty vanished from our streets…and with their going the ordeal through which we passed will seem remote, unreal, perhaps forgotten.”

In the booklet’s foreword, the Very Reverend W. R. Matthews, then the Dean of St. Paul’s, claimed that “the devastation of war has given us an opportunity which will never come again.” This optimism echoed sentiments expressed during the war itself. The country would turn bombsites into social housing and hospitals, with a few churches left as memorials to the carnage of the home front. (As Brian Foss has pointed out, it wasn’t until September 1941 that frontline casualties outnumbered civilian deaths in Britain.) The short booklet is full of halftone illustrations, architectural plans, and garden plans, showing how to transform destroyed buildings into “ruins.” In one article, Hugh Casson argued that “every stone—whether fallen or in place—is a fragment of the past, part of the pattern of history.” Churches such as St. Dunstan and Christ Church, Newgate Street, scarred by the Great Fire of London and the Blitz, are now living monuments not just to the bombs and fires, but to London’s long history of transformation. Casson worried about a time when “all traces of war damage will have gone, and its strange beauty vanished from our streets…and with their going the ordeal through which we passed will seem remote, unreal, perhaps forgotten.”

more here.

Can Chess Survive Artificial Intelligence?

Yoni Wilkenfeld at The New Atlantis:

Last August, two dozen of the strongest chess players in the world met for a new kind of tournament. The ground rules were unforgiving: Each player would start with only fifteen minutes on the clock per game, competing in scores of back-to-back games against all the others multiple times. Players were eliminated in stages until only two remained, who would go on to play two hundred games to decide the champion. Competitors hailed from around the world, though a sizeable minority were American. All would face the constant scrutiny of fans through an online broadcast of the tournament on Twitch, a streaming website. A month of grueling play later, a victor emerged: Stockfish 220818, the strongest chess computer to date.

Last August, two dozen of the strongest chess players in the world met for a new kind of tournament. The ground rules were unforgiving: Each player would start with only fifteen minutes on the clock per game, competing in scores of back-to-back games against all the others multiple times. Players were eliminated in stages until only two remained, who would go on to play two hundred games to decide the champion. Competitors hailed from around the world, though a sizeable minority were American. All would face the constant scrutiny of fans through an online broadcast of the tournament on Twitch, a streaming website. A month of grueling play later, a victor emerged: Stockfish 220818, the strongest chess computer to date.

While many past computer chess competitions had the human programmers convene in person, in the Computer Chess Championship, teams submitted their software to run on the servers of Chess.com, which hosted the event. The Twitch feed showed not only the live game play, but “a real-time peek into” each program’s “thinking process and the lines they are considering,” said a post announcing the tournament. The website ran a single game at a time, back to back, with uninterrupted play for a month.

more here.

David Hammons Taunts the Art World

Rachel Wetzler at Art in America:

The difficulty of Hammons’s work is that it seems to preempt any possible critical response and offer up an implicit rebuttal. This was most evident in the centerpiece of the show, a grid of tents pitched in the gallery’s interior courtyard, which is located between the entrance to the gallery’s chic, industrial compound and the exhibition spaces. Each tent bore a stenciled threat: this could be u. My first reaction was dismissive; the installation seemed too obvious, too lazily reliant on a contextual friction that was intended to point to a larger one, since the gallery—a sign of advanced gentrification if ever there was one—sits just a few blocks from the homeless encampments of Skid Row. OK, we’re all complicit: now what?

The difficulty of Hammons’s work is that it seems to preempt any possible critical response and offer up an implicit rebuttal. This was most evident in the centerpiece of the show, a grid of tents pitched in the gallery’s interior courtyard, which is located between the entrance to the gallery’s chic, industrial compound and the exhibition spaces. Each tent bore a stenciled threat: this could be u. My first reaction was dismissive; the installation seemed too obvious, too lazily reliant on a contextual friction that was intended to point to a larger one, since the gallery—a sign of advanced gentrification if ever there was one—sits just a few blocks from the homeless encampments of Skid Row. OK, we’re all complicit: now what?

But the installation posed a problem for would-be visitors: to walk right by the piece en route to the exhibition would reproduce a kind of everyday callousness; to solemnly admire it would be perverse and self-congratulatory; and to feel offended by its hypocrisy or aestheticization of a social crisis would be equally so: imagine being preoccupied by the dubious politics of an artwork about homelessness when there’s a real tent city down the street—care about that instead.

more here.

Culture Worriers: The libertarian struggle to understand contemporary art

Rachel Wetzler in The Baffler:

THE CATO INSTITUTE, “a public policy research organization dedicated to the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace,” was founded in 1977 by the Koch brothers, the anarcho-capitalist economist Murray Rothbard, and former Libertarian Party national chair Ed Crane. At the time, libertarianism was still considered a fringe ideology for paranoid California eccentrics, derided even by one of their own patron saints, Ayn Rand, as a bunch of unserious “hippies of the right.” In order to bring Austrian economic theory and “minarchism” into the political mainstream, libertarianism needed a rebrand; the answer was naturally a Washington think tank, where its vision of a world of unfettered capitalist exchange could be tidily packaged into incremental policy proposals and fed to right-wing legislators.

THE CATO INSTITUTE, “a public policy research organization dedicated to the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace,” was founded in 1977 by the Koch brothers, the anarcho-capitalist economist Murray Rothbard, and former Libertarian Party national chair Ed Crane. At the time, libertarianism was still considered a fringe ideology for paranoid California eccentrics, derided even by one of their own patron saints, Ayn Rand, as a bunch of unserious “hippies of the right.” In order to bring Austrian economic theory and “minarchism” into the political mainstream, libertarianism needed a rebrand; the answer was naturally a Washington think tank, where its vision of a world of unfettered capitalist exchange could be tidily packaged into incremental policy proposals and fed to right-wing legislators.

Though Cato rejects the label “right-wing,” loudly proclaiming its independence from any political party and its commitment to fighting all efforts to expand state power, whether it comes in the form of Obamacare or the Iraq War, its relationship with the GOP has largely been more symbiotic than combative. Republicans can forgive Cato’s advocacy for, say, the decriminalization of drugs as a naïve and misplaced ideological rigidity because it comes with an economic agenda they can get behind: drastic tax cuts, the privatization of virtually all social services, and the elimination of anything that might get in the way of free trade, from environmental regulations to child labor laws. Cato denies the gravity of climate change (which it dismisses as pseudoscientific alarmism), believes in the right of business owners to discriminate on the basis of race, and ardently defends corporate personhood (“So What if Corporations Aren’t People?” reads the inadvertently hilarious title of a law review paper by Cato legal scholar Ilya Shapiro in support of the Citizens United decision).

More here.

What Do You Do When You’re Alone

Olivia Laing in IAI News:

Loss is a cousin of loneliness. They intersect and overlap, and so it’s not surprising that a work of mourning might invoke a feeling of aloneness, of separation. Mortality is lonely. Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving inexorably towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture. Then there’s the loneliness of bereavement, the loneliness of lost or damaged love, of missing one or many specific people, the loneliness of mourning.

Loss is a cousin of loneliness. They intersect and overlap, and so it’s not surprising that a work of mourning might invoke a feeling of aloneness, of separation. Mortality is lonely. Physical existence is lonely by its nature, stuck in a body that’s moving inexorably towards decay, shrinking, wastage and fracture. Then there’s the loneliness of bereavement, the loneliness of lost or damaged love, of missing one or many specific people, the loneliness of mourning.

Loneliness as a desire for closeness, for joining up, joining in, joining together, for gathering what has otherwise been sundered, abandoned, broken or left in isolation. Loneliness as a longing for integration, for a sense of feeling whole. It’s a funny business, threading things together, patching them up with cotton or string. Practical, but also symbolic, a work of the hands and the psyche alike. One of the most thoughtful accounts of the meanings contained in activities of this kind is provided by the psychoanalyst and paediatrician D. W. Winnicott, an heir to the work of Melanie Klein. Winnicott began his psychoanalytic career treating evacuee children during the Second World War. He worked lifelong on attachment and separation, developing along the way the concept of the transitional object, of holding, and of false and real selves, and how they develop in response to environments of danger and of safety.

In Playing and Reality, he describes the case of a small boy whose mother repeatedly left him to go into hospital, first to have his baby sister and then to receive treatment for depression. In the wake of these experiences, the boy became obsessed with string, using it to tie the furniture in the house together, knotting tables to chairs, yoking cushions to the fireplace. On one alarming occasion, he even tied a string around the neck of his infant sister.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Questions by the Lake

When, after two years you returned to Solentiname,

already a child of five, Juan,

I remember very well what you said to me:

“You’re the one who’s going to tell me all about God, right?”

And I who all the time

have come to know less about God.

A mystic, that is, a lover of God

called God NOTHING,

and another said: all that you say about God is false.

And if you were to have knowledge of God it was better

perhaps I didn’t talk to you of God.

But once,

I certainly spoke to you of God by the lake,

on the dock,

during a twilight all pink and silver:

“God is one who’s within all of us,

within you, within me, within everywhere.”

“And God is within that heron?” “Yes.” “And within the sardines?”

“Yes.” “And within those clouds?” “Yes.”

“And within that other heron?” “Yes.”

A tiny Adam naming all your small paradise.

“And God is within this dock?” “Yes.” “And within the waves?”

Why do children ask so many questions?

And I

why do I question why

like a child?

“And God is also within my dad and my mom?” “Yes, God is.”

And you told me:

“But God doesn’t get to the island of the bad ones, right?”

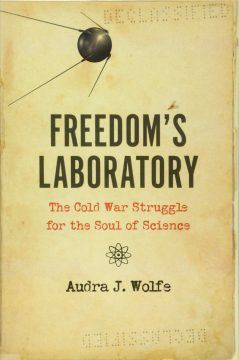

Is Science Political?

Michael D. Gordin in the Boston Review:

The word “science” typically evokes epistemic ambitions to explore the fundamental laws of the natural world. This is the stuff of philosophical reflection and documentary specials—and it is unquestionably important. This ethereal vision of science appears starkly divorced from the messy fray of “politics,” however you might want to understand the term.

The word “science” typically evokes epistemic ambitions to explore the fundamental laws of the natural world. This is the stuff of philosophical reflection and documentary specials—and it is unquestionably important. This ethereal vision of science appears starkly divorced from the messy fray of “politics,” however you might want to understand the term.

Yet consider two other central features of today’s science: it is elite, and it is expensive. By elite, I do not mean that only certain sorts of people—the “right sorts”—have the capacity to do science. What I mean is that you cannot just pick up and decide today that you are going to be a scientist. It requires years, even decades, of training in the methods and practices of inquiry; consulting a scientist means that you are obligated to turn to someone who has already undergone that process. You do science with the scientists you have, regardless of whether they are socially or politically agreeable to you.

The expense of science is related. Especially since the end of World War II, research in cutting-edge areas of science consumes vast resources: particle accelerators, satellites, genome sequencers, large-scale field surveys, and all the monies invested in the training of those elite scientists. Someone has to pay for that. In the United States, at first that “someone” was philanthropy (such as the Rockefeller Foundation) or industry (Bell Labs), but during the Cold War it was, increasingly, the state.

More here.