by Ruchira Paul

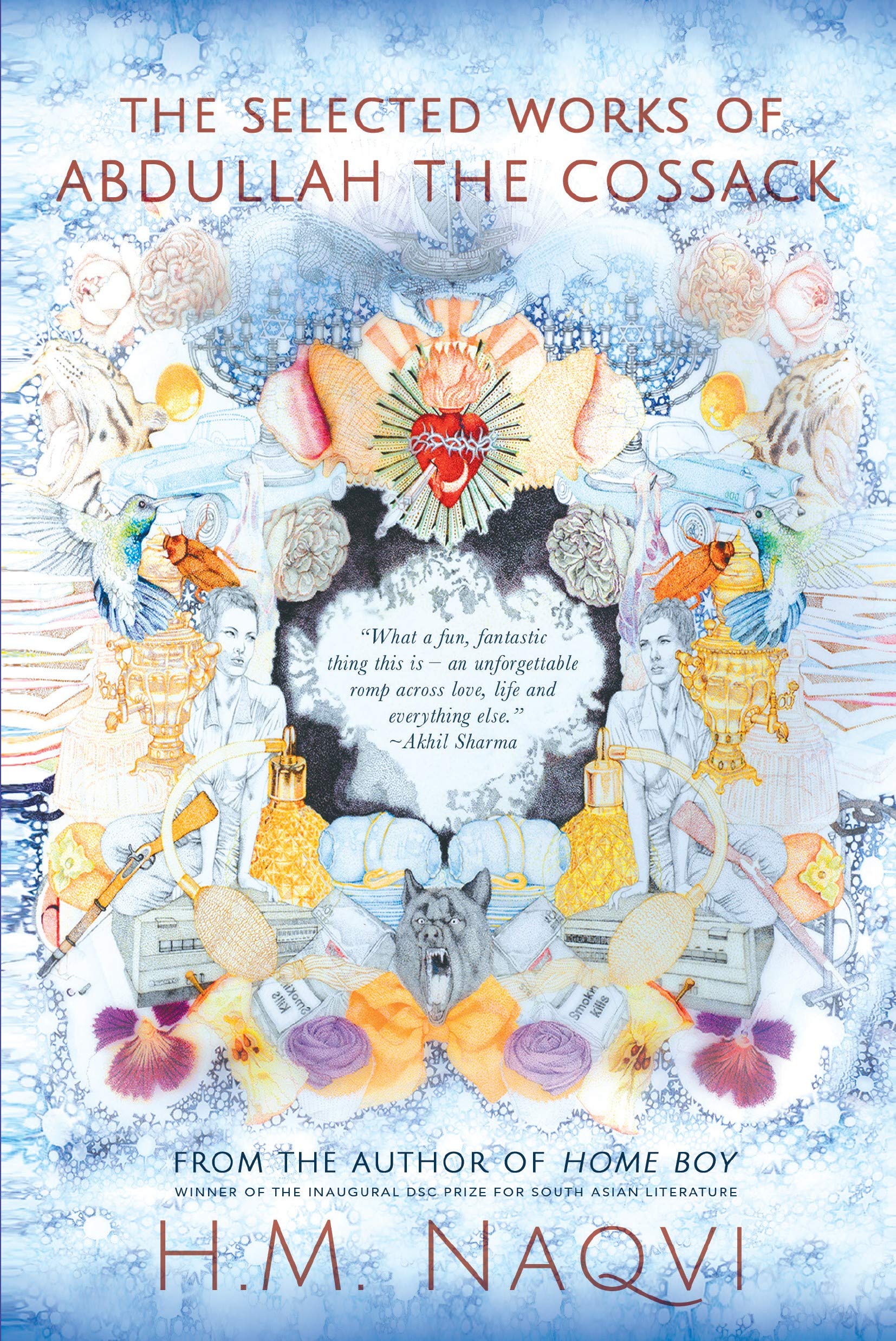

Early in H.M. Naqvi’s new novel The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack (SWAC from here on out) we come across this exchange between Abdullah and a devout young Pathan as the former, in poor health and out of breath, is seen taking a drink of water from a thermos on a sweltering day during the holy month of Ramzan when most able bodied and observant Muslims choose to fast between sunrise and sunset.

Early in H.M. Naqvi’s new novel The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack (SWAC from here on out) we come across this exchange between Abdullah and a devout young Pathan as the former, in poor health and out of breath, is seen taking a drink of water from a thermos on a sweltering day during the holy month of Ramzan when most able bodied and observant Muslims choose to fast between sunrise and sunset.

“Tum Musalman ho?” asks the younger man offended by Abdullah’s transgression. “Are you a Muslim?”

Enraged by the man’s pious arrogance, Abdullah hollers, “This is Currachee! This is my city! I could be a Catholic, Protestant, Pentecostal, Hindoo, Amil, Parsee. I could be Shia, Sunni, Bohra, Barelvi, Sufi….If you want to ask such questions then go back to Kabul. …If you are sensible, then your God is sensible, but if you’re a dolt, your God’s a dolt.”

A dangerous confrontation follows from which the beleaguered Abdullah is rescued by a dark eyed stranger. Abdullah’s defiant bluster notwithstanding, the reader knows that in today’s Pakistan, even a Muslim in a Muslim nation and a lifelong resident of a large and cosmopolitan city like Karachi, a man cannot really expect to have his seeming lack of piety go unchallenged. Many of the adherents of other faiths on the list that Abdullah rattles off no longer live there and the few that do, are marginalized and often live in fear. Not just in Pakistan but in many parts of the world triumphalist majoritarian bullying now pervades the public mood.

Across the border in India, Muslims who have lived there for generations and over many centuries are routinely asked by militant Hindus to prove their Indian bona fides, sometimes with lethal consequences. Donald Trump (and his jeering supporters at a campaign rally) recently asked four American congresswomen of color to go back where they came from because their profiles and politics do not fit his definition of what it is to be an American.

SWAC is a fast moving novel about a man and the city he loves – Karachi. Abdullah the Cossack acquired the Slavic honorific as a young man, when egged on by a bartender’s bet he once outdrank a group of hard drinking visiting Soviet technocrats and then held aloft a bottle of Cossack Vodka as the symbol of victory. He is the third son born in a well to do and influential family of Karachi. His father, a hotel owner and businessman had connections in high places. His doting mother, a beautiful and hard working woman expected Abdullah to become a successful man. Instead of striking out on his own Abdullah fell into the role of his father’s assistant in the high class hospitality business in his early youth. A bon vivant, polymath, shrewd, compassionate and the beloved uncle to his two young nephews (the Childoos) we first meet Abdullah on his seventieth birthday, a toothless old man with many maladies – obesity, diabetes, painful hemorrhoids and periodic depression – who has nothing to show officially for a life well spent.

Waking up on his 70th birthday feeling unwell and worthless Abdullah contemplates suicide by jumping off the third floor balcony of Sunset Lodge, the once opulent family mansion now sliding into decrepitude. He is saved first by the sudden distraction caused by a pair of “obsidian eyes” spying on him like a phantom over the compound’s boundary wall and very soon thereafter by the summons to answer the telephone. Both events go on to dramatically change the Cossack’s life. The pair of eyes later turn out to belong to Jugnu, his savior from the Pathan’s wrath whom we met earlier. A garishly glamorous person of indeterminate gender and a shady past, Jugnu becomes Abdullah’s object of passionate love and unflagging admiration. Jugnu would become a dependable companion and his Guardian Angel when Abdullah is confronted with danger to his life and livelihood emanating both from within his own family and the deadly crime syndicate of Karachi. The phone call comes from an old friend Felix Pinto, a brilliant Goan jazz musician aka Caliph of Cool, with whom Abdullah had lost touch for many years. Over the telephone, Pinto invites him to drop by at the Goan Association of Karachi and see him. After a boozy and music filled evening to celebrate Abdullah’s birthday, the Caliph of Cool asks him for a favor – to take responsibility for the education and safety of his young grandson Bosco.

Saddled with his new found love for Jugnu and faced with the onerous but not unpleasant task of attending to the educational, moral and practical mentoring of young Bosco, Abdullah finds a new lease on his moribund life. (Alongside these responsibilities, he also harbors a long standing dream that weighs on his mind – recording the Mythopoetic Legacy of Abdullah Shah Ghazi, the patron saint of Karachi) With the help of these two accomplices Abdullah embarks upon a bumpy ride late in life which in turn is both hilarious and fraught with unexpected peril. On the way, the reader is served up nuggets of the Cossack’s personal profundity on subjects as varied as philosophy, religion, philology, gardening, the pre and post Islamic history and politics of Pakistan, the region’s changing geological features and architectural facade, the country’s saints and villains as also the quickest recipe for making Chicken Karahi.

SWAC is the first book by Naqvi that I have read. Naqvi is an elegant writer and his writing, both in style and content, brought to mind a few other authors I have read. His frenetic and scattershot narrative is somewhat similar to that of Salman Rushdie. The nostalgic, loving tribute to the city of Karachi (and to some extent, a more tolerant and multicultural Pakistan of the early years) reminded me of the French writer Jean Claude Izzo’s Marseille Trilogy – crime novels that double as a paean to the French port city, a place which is long past its glory days but continues to fascinate and despair. The Karachi of yore, a vibrant place with a rich mosaic of history and culture where Muslims, Hindus, Parsis, Goan Christians and Jews1 once lived, socialized, did business, cavorted together and their separate places of worship dotted the city’s landscape, now lives mostly in Abdullah’s memory. Even after most of his Christian, Hindu, Jewish and Goan friends are gone and Pathans from the northwest have taken up residence there, Karachi still thrives as a sprawling megapolis whose newfound pious hypocrisy and inept municipality are not at all to Abdullah’s liking. The new Karachi, just like the old one, is marked by the dazzling outward urban glitter of some areas, filthy abysmal poverty of others and the crime ridden and unsavory underbelly of both. The city of Karachi, in all its avatars, is as much a character in the novel as its human occupants.

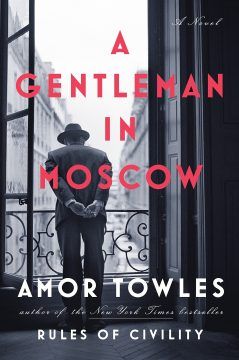

The plot of SWAC to me was most reminiscent of A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. The experiences and adventures of Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, an erstwhile aristocrat confined to a garret apartment in Moscow’s Hotel Metropol by the Bolsheviks in Towles’ novel have many parallels with the rambunctious and somewhat more scatological life story of Abdullah the Cossack. Both sophisticated aging men of the world, severely reduced in their physical vigor and social circumstances are still agile of mind with prodigious memories. During a particularly bleak moment in their lives the Count and the Cossack contemplated ending their misery by taking a flying leap from a high place but were pulled back from the precipice by an unexpected and somewhat comical interruption. They embark on late life romances with striking and shrewd partners who become their comrades in arms in unexpected adventures and calculated subterfuges to thwart the enemy. The duty of grooming a young ward to navigate a fast changing and often dangerous world is thrust upon each man by a long unseen beloved friend when he is least prepared for it. The Count and Abdullah undertake to perform their unlikely roles dutifully and both are reinvigorated by the challenge.

The plot of SWAC to me was most reminiscent of A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. The experiences and adventures of Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov, an erstwhile aristocrat confined to a garret apartment in Moscow’s Hotel Metropol by the Bolsheviks in Towles’ novel have many parallels with the rambunctious and somewhat more scatological life story of Abdullah the Cossack. Both sophisticated aging men of the world, severely reduced in their physical vigor and social circumstances are still agile of mind with prodigious memories. During a particularly bleak moment in their lives the Count and the Cossack contemplated ending their misery by taking a flying leap from a high place but were pulled back from the precipice by an unexpected and somewhat comical interruption. They embark on late life romances with striking and shrewd partners who become their comrades in arms in unexpected adventures and calculated subterfuges to thwart the enemy. The duty of grooming a young ward to navigate a fast changing and often dangerous world is thrust upon each man by a long unseen beloved friend when he is least prepared for it. The Count and Abdullah undertake to perform their unlikely roles dutifully and both are reinvigorated by the challenge.

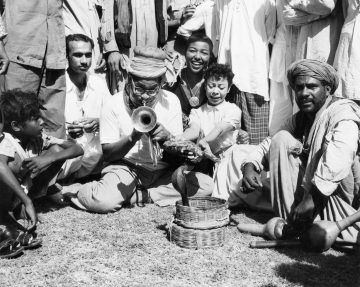

Naqvi employs some quirky literary flourishes in his book. Some words are spelt in the archaic and obsolete British way – Currachee for Karachi, Hindoo for Hindu and Scinde for Sindh. More noticeable is the prolific use of footnotes which some may find irksome and distracting. But for me the footnotes worked well by providing context – religious, cultural, geological, historical, political and sometimes plain tongue in cheek. Despite his idiosyncratic style and the narrative digressions, Naqvi tells a straightforward story seamlessly weaving together the fictional life of a man with facts about the changing faces of Karachi. Not knowing much about Pakistan’s history, I looked up some of the historical tidbits that dot the story line of SWAC. Dizzy Gillespie did once visit Karachi and dazzled the city’s jazz lovers and charmed a cobra.

* * *

Now my own single footnote: 1 I am very interested in the history of Jews of the Indian subcontinent, a small, diverse and once thriving community which has now for the most part disappeared. Most of my readings so far have related to erstwhile Jewish residents of what is now India, in cities like Pune, Kolkata, Kochi, Mumbai and some parts of the Malabar Coast. I didn’t have much information about Jews who once lived in parts of British India that is now Pakistan.

In “The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack,” I came across several references to Jewish businesses, entrepreneurs, architects and civil servants and Jewish synagogues (Yahoodi Masjids) that were once part of the landscape of Karachi and other Pakistani cities. Abdullah refers to his Jewish friends and mentions in passing that the design of Sunset Lodge, his father’s mansion, was conceived by Moses Somake, a real life Baghdadi Jew born in Lahore. Somake designed many of Karachi’s landmark buildings which still stand. The Jewish presence in both India and Pakistan is now mostly a thing of the past. India still has a small community of elderly Jews whereas in Pakistan probably none (or very few) remain. And those who remain, according to Naqvi, probably choose to pass as Parsi or Christian in public.

The reference to Pakistani Jews led me to do some digging and I came across this short article which contains some lovely old photos.