Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

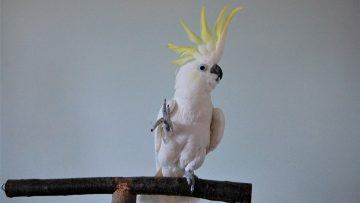

Before he became an internet sensation, before he made scientists reconsider the nature of dancing, before the children’s book and the Taco Bell commercial, Snowball was just a young parrot, looking for a home. His owner had realized that he couldn’t care for the sulfur-crested cockatoo any longer. So in August 2007, he dropped Snowball off at the Bird Lovers Only rescue center in Dyer, Indiana—along with a Backstreet Boys CD, and a tip that the bird loved to dance. Sure enough, when the center’s director, Irena Schulz, played “Everybody,” Snowball “immediately broke out into his headbanging, bad-boy dance,” she recalls. She took a grainy video, uploaded it to YouTube, and sent a link to some bird-enthusiast friends. Within a month, Snowball became a celebrity. When a Tonight Show producer called to arrange an interview, Schulz thought it was a prank.

Before he became an internet sensation, before he made scientists reconsider the nature of dancing, before the children’s book and the Taco Bell commercial, Snowball was just a young parrot, looking for a home. His owner had realized that he couldn’t care for the sulfur-crested cockatoo any longer. So in August 2007, he dropped Snowball off at the Bird Lovers Only rescue center in Dyer, Indiana—along with a Backstreet Boys CD, and a tip that the bird loved to dance. Sure enough, when the center’s director, Irena Schulz, played “Everybody,” Snowball “immediately broke out into his headbanging, bad-boy dance,” she recalls. She took a grainy video, uploaded it to YouTube, and sent a link to some bird-enthusiast friends. Within a month, Snowball became a celebrity. When a Tonight Show producer called to arrange an interview, Schulz thought it was a prank.

Among the video’s 6.2 million viewers was Aniruddh Patel, and he was was blown away. Patel, a neuroscientist, had recently published a paper asking why dancing—a near-universal trait among human cultures—was seemingly absent in other animals. Some species jump excitedly to music, but not in time. Some can be trained to perform dancelike actions, as in canine freestyle, but don’t do so naturally. Some birds make fancy courtship “dances,” but “they’re not listening to another bird laying down a complex beat,” says Patel, who is now at Tufts University. True dancing is spontaneous rhythmic movement to external music. Our closest companions, dogs and cats, don’t do that. Neither do our closest relatives, monkeys and other primates.

More here.