Peter Martin in Aeon:

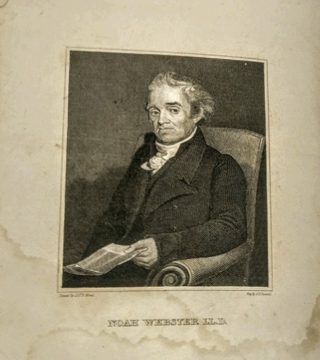

In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.

In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.

Webster saw himself as a saviour of the American language who would rescue it from the corrupting influence of British English and prevent it from fragmenting into a multitude of dialects. But as a linguist and lexicographer, he quickly ran into trouble with critics, educators, the literati, legislators and much of the common reading public over the bizarre nature of his proposed language reforms. These spelling reforms – for example, wimmen for ‘women’, greeve for ‘grieve’, meen for ‘mean’ and bred for ‘bread’ – were all intended to simplify spelling by making it read the way that words were pronounced, yet they brought him the pain of ridicule for decades to come.

His definitions were regarded as his strong suit, but even they frequently rambled into essays, and many readers found them overly aligned with New England usage, to the point of distortion. Surfeited with a Christian reading of words, his religious or moral agenda also shaped many of his definitions into mini-sermons or moral lessons rather than serving as clarifications of meaning.

More here.