by Dave Maier

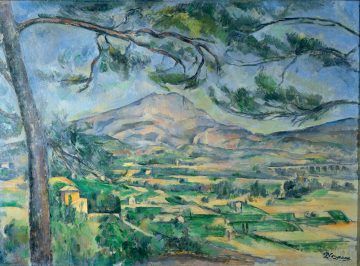

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

Nothing has really seemed to fit everything, and for whatever reason, essentialism in the philosophy of art, or at least arguing about it in public anyway, has drifted in and out of fashion. Yet that question, or something like it, won’t simply go away. Unless everything is art, some things are art and some are not. What’s the difference?

When you get stuck like this, one way to get back on track is to ask a different question. There are plenty of worthwhile candidates, but one which keeps coming up for me is: what’s the difference between something that’s not art because it’s not good enough, and something that’s not art because it’s the wrong sort of thing? Let’s start there.

This seems like a natural distinction to make. Painting is unquestionably an art form: it’s the sort of thing that Cézanne’s masterpieces are. Every painting, then, would be the right sort of thing to be art; but not all paintings count as art, because lots of them simply aren’t good enough. (Any that I would do, for example, would fall into this category.) We don’t put things in the art museum simply because they’re paintings. That is, art is not simply a descriptive but also a normative concept, which may help explain why definition has been so difficult (although that can’t possibly be the whole story, or a lot of moral philosophy has been pointless from the word go).

On the other hand, we want to rule out as non-art plenty of things we are not thereby evaluating. We do of course use the word “artist” to praise the skills of all kinds of practitioners, from tennis players to chefs to conmen, but I take it as (provisionally) given that these activities are not artistic in our sense. Roger Federer may want to wow us with his skills; but his first objective, qua tennis player, is to win the match.

So, a natural distinction; but even here there are complications. First, it seems that whenever we try to separate Xs from non-Xs we bring norms into it. Even the best non-X, considered as a potential X, isn’t “good enough” to be an X. That can sound funny in particular cases (say X = vermin or something else unpleasant), but in others it sounds fine (enough, again, to seem to blur our distinction between the two questions).

Second, or in particular, when we think of art as something uniquely valuable, we might very well think of non-art as (not simply not meeting all of the necessary criteria, but also as) falling short of that unique value: i.e., not good enough in the relevant sense. If I desire the characteristically aesthetic buzz of great art, I’m telling you now: don’t take me to the restaurant, no matter how good it is. The chef will fail to provide the (type of) experience I desire.

Let’s put the complications aside for now, and simply recognize that normative and descriptive judgments are conceptually intertwined, without taking that to threaten our very enterprise, which we can slightly reconstrue as that of trying to understand (not What Art Is, but instead) what we like about art that makes us want to single it out as characteristically artistic.

—

I’ve always liked the image John Dewey uses in the second paragraph of Art as Experience. That which has made aesthetic theory seem necessary, he complains, is the very thing which makes it impossible: the existence of universally admired works of art.

Art is remitted to a separate realm, where it is cut off from that association with the materials and aims of every other form of human effort, undergoing, and achievement. … [Our primary task is thus] to restore continuity between the refined and intensified forms of experience that are works of art and the everyday events, doings, and sufferings that are universally recognized to constitute experience. Mountain peaks do not float unsupported; they do not even just rest upon the earth. They are the earth in one of its manifest operations. It is the business of those who are concerned with the theory of the earth, geographers and geologists, to make this fact evident in its various implications. The theorist who would deal philosophically with fine art has a like task to accomplish.

We don’t need to endorse Dewey’s particular conception as foreshadowed here (as well as in, duh, the title of his book) to appreciate the importance of conceptual continuity between the artistic masterpieces which motivate our inquiry and, well, whatever other things we decide there are nearby (that is, not just “experience”).

This lines up nicely with Wittgenstein’s similar declaration, in Philosophical Investigations §122, that of “fundamental significance” to his method is “produc[ing] just that understanding which consists in ‘seeing connections.’” “Hence,” he continues, “the importance of finding and inventing intermediate cases.” We see what looks like, but is not yet advertised as, such a case a bit earlier, in §78:

Compare knowing and saying:

how many feet high Mont Blanc is—

how the word “game” is used—

how a clarinet sounds.

His comment there is: “If you are surprised that one can know something and not be able to say it, you are perhaps thinking of a case like the first. Certainly not of one like the third.”

Here, Wittgenstein’s interest is in the intermediate case itself (“how the word ‘game’ is used,” the overt subject of that part of the book). In our somewhat different context, I propose that we use intermediate cases along the axes of both of our paired questions above to get a sense of the structure of the conceptual space in which the relevant phenomena occur.

The first type of intermediate case we have already seen. Instead of thinking about tennis and so on as test cases for, or counterexamples to, proposed definitions of art, we can think of them as what I like to call “para-art.” A paramedic or paralegal is not a doctor or a lawyer, but whether that matters will depend on what exactly we need them to do at any particular time. Similarly, depending on what we’re talking about, para-art may manifest qualities which need not be disqualified as non-artistic simply because para-art is non-art, and may in fact provide just the object of comparison which will shed the proper light (again, in the context).

A huge range of phenomena might be considered para-artistic, and I leave the generation of examples as an exercise for the reader. Why each can, if necessary, be distinguished from art proper is, again, not our main interest here, but the usual reason would have to be that it has a characteristic aim or purpose which trumps any artistic aims the maker may also have. Many such examples can be grouped under the name “crafts.” Plenty of people have argued in favor of elevating crafts to the level of art. Traditional quilting, for example, often shows a significant degree of what there’s no reason not to call artistry, and supporters often point to sexist and elitist assumptions about art needing to come from traditionally male professional artists rather than mere housewives. As an activity, though, quilting seems importantly different from the sort of thing that, say, Cézanne or Shostakovich did.

For one thing, quilters get together to make quilts because quilts are useful in rather a more immediate way than are string quartets or paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire. No artistry can make something into a successful quilt if it is too thin or too delicate or cannot be lifted by ten strong men together. Nor can the existence of a thing which is both an artwork and a quilt (plenty of quilts hang in museums of contemporary art) make quilting into an artform if it isn’t already. More generally, crafts must succeed first as the sort of thing they are in order to have any chance of being art as well.

On the other hand, the very idea of practical constraint can’t be enough by itself to disqualify something as art. Architecture is an accepted artform, but a successful building can’t fall down any more than a successful quilt can fall apart. There’s plenty of classical music which was meant to be dance or dinner music and operates within those constraints without thereby failing to count as art music. The examples can easily be multiplied (portraits, commissioned works with constraints provided by the patron or client, genre constraints like science fiction or romance, etc.). Also, of course, external constraints can provide opportunities for artistic innovation or mastery all by themselves, and can often be self-imposed.

We must step carefully here. Our method is designed not to arrive at theoretical conclusions but instead to give disparate but related phenomena the conceptual space they need to breathe. Whatever quasi-artistic virtues quilting may have are more easily seen and understood if we refrain from simply elevating it and other crafts into what is now the more prestigious category, and note instead the variety of ways in which certain creative phenomena can be manifested, the better to understand all of them.

If quilters deserve more credit, then let’s give it to them. If “art proper” isn’t as uniquely valuable as we tend to assume, then let’s modify our views about it. But we can do this without conflating importantly different things, even as we recognize similarities which we had been missing. To say this is not to hold fast to this or that exclusive theory or definition of art, but instead just the opposite: to deny or at least defer the importance of so doing.

The point of the concept of para-art, again, is to be able to discuss the artistic aspects of certain things without being sidetracked by the question of whether these aspects are “enough” to qualify the thing as art. We need to make it possible for that issue, in the context, not to matter, or it will overshadow the things we’re actually interested in. This takes conscious effort, as not only does this go against the usual procedure, but is often the first thing we think of when these things come up in the context of what art is and is not: how about wine, or bonsai, or sex? If these are clearly para-arts, rather than debatably art or non-art, then we won’t prioritize that debate over other things.

We have another axis to consider, but let’s take a quick look at another kind of para-art just to flesh the concept out a little. Another category of para-art (besides crafts or games) is what we might call proto-art. The history of technology in the last century or two has naturally made possible new ways of making art; but new artforms do not spring fully formed, Minerva-like, from the head of Zeus. Much as we honor them as pioneers, we may not want to hold up the works of Thomas Edison or the Lumière brothers as mature artworks, simply because to be an artist is, we may feel, to work within an established tradition, at least to the extent that the first one to do X will likely not be the first X-artist. We do speak of “experimental art,” but this is just another reason to utilize the concept of para-art to defer undue decisions of whether such things “count as art.” (Edgard Varèse, when tagged with that label, famously replied that “all my experimenting is done before I compose.”) In any case we will want to be able to track the early, possibly tentative strivings of a proto-artform without worrying about when exactly to drop the prefix.

This can lead to interesting results not only when one person’s proto-art is another’s established art, but also when a third person has it as neither one nor the other but instead another kind of para-art (or non-art). If cinema is not an artform proper (or was not yet one in, say, 1900), then is that because, like crafts, it isn’t (and could not be) the right sort of thing (as Roger Scruton for example claims)? or instead because it had not yet developed the necessary traditions or techniques? If we are careful, we can defer this question even in the face of a three-way dispute, and still understand the properly aesthetic significance of, say, the invention of color film.

—

So much for para-art. We’ll have a better sense of what our space looks like if we expand our picture along the other axis: that of whether a work is “good enough” to be art.

Remember Dewey’s image of the mountain which is not on top of, nor separated from, but instead is the earth in one of its manifestations, and that restoring continuity is more important than ratifying that separation with aesthetic theory. Still, any account of the nature of art will naturally focus on, and be primarily tested by, the artistic masterpieces which provoke our interest in the first place. Just as we have no reason to deny the qualitative differences between crafts and art proper, though, but instead accommodate them with the concept of para-art, we can do much the same thing when dealing with the very real difference between artistic masterpieces and works of art which are (merely) successful. Here the latter is an intermediate case between the former and works which are more clearly inferior, and indeed those too bad (like my own hypothetical paintings) to be art at all, even if they are, unlike crafts, the right sort of thing.

Let’s call these intermediate-level works, which after all constitute the majority of what we consider successful art, “three-star works” (out of four). The paradox of three-star works is that, as I will argue, they are the backbone of the form, on which four-star works depend; but four-star works are in some way “better,” and quite naturally seem to be the place to look to understand the lesser works, which don’t do as well what they themselves do better. In explicitly Platonic terms (ironically enough, since Plato himself banished art to the realm of mere appearance), four-star works seem better to instantiate the ideal than do their lesser siblings.

But is that really the right way to look at it? In my view, just as we must understand the earth if we are to see what mountains are, we must not ignore — indeed, I think we must focus on — the mainstream of successful art in order to understand masterpieces, not the other way around. Without three-star works, there can be no four-star works. What the former do, the latter either do in a new or markedly better way, or pointedly avoid doing, in order to do something provocatively new by comparison. In either case, the former must stand by themselves: it’s not that they try to do what masterpieces do, but fail. Remember, we’re not talking about my own paintings, but instead successful artworks which simply lack whatever it is that prevents them from being helpfully considered masterpieces. That is, they might not fail at all; and we must be particularly careful, while we try to understand what they don’t do, not to miss what they do.

The intermediate category seems almost to be the more interesting one in any case. While some three-star works may lack apparent flaws, settling for the solidly meritorious, others would be masterpieces themselves without that extra something that doesn’t quite fit. Maybe even that very uneven nature is what gives the flawed masterpiece the sort of interest that it has, or made possible what would otherwise (say, for that non-genius artist) be out of reach. Possibly a flawed but ambitious work opens up exciting new vistas which the more carefully flawless masterpiece, minding its own exquisite garden to perfection, does not. The differences, that is, between four and three can be just as much qualitative as quantitative. As befitting intermediate cases, there will also be comparable differences at the other end, where competence shades into intermittent and finally outright failure (my own paintings again), where even the very lack of aesthetic value can be surprisingly instructive.

It may also be instructive, putting our two dimensions together, to put the masterpieces to one side and compare the less distractingly idiosyncratic three-star works of art with para-art of the various levels of quality. If we had been tempted to undervalue para-art in the context of deciding What Art Is, a comparison in which the para-artist comes out equal or better may allow that distracting issue, again, to slide into the background. As always, context will decide.

That’s all for now; maybe later we can take this method out for a test drive. Happy Memorial Day!